Tim Dobermann Increased food insecurity resulting from climate change is a big threat to many individuals living in the developing world, and likely to become increasingly so, especially with inadequate action on mitigation, as we're currently seeing. Unfortunately, the inequality of climate change means we will see the greatest health impacts falling on the world’s poorest – and those least responsible for the problem. Naturally, agriculture is a key issue for many parties here at COP. For much of Africa and South Asia, the incomes and health are directly linked to the yields of their crops. Moreover, it is one of, if not the most, climate-sensitive sectors. That agriculture can play a key role in both adaptation and mitigation - and that they need to be integrated better - has been a common theme voiced in many events thus far. Better management practices and techniques such as conservation tillage or proper application of fertilisers can both reduce emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (among others) and improve the resilience of smallholder farmers in the face of climate change – and so help to protect against malnutrition. Frustrations and setbacks Unfortunately, in a late night (or more accurately early morning) session of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), it became clear that no formal progress on establishing a working group or body to focus on agriculture would be made. Perplexing to those outside the negotiations – but, as it seems, entirely normal within them – is that all sides agree on the importance of raising efforts into climate-smart agriculture, yet no substantial agreement can be found and so it has had to be pushed to the agenda for COP20 in Lima next year, to many Parties’ and NGOs' dismay. Farmers and their families deserve so much better. Silver linings However, there is some good news amongst the largely frustrating negotiations. Comparatively little attention has been given to the advancements thamade in reducing emissions through deforestation and land degradation (REDD+), where the plus represents considerations about biodiversity and local and indigenous communities’ rights. Forests serve as natural ‘carbon sinks’, which take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen through photosynthesis. Parties have quickly recognised these benefits, and have readily moved towards mechanisms which can help to incentivise and implement these types of projects. Brazil has made significant leaps in reducing its emissions by combating deforestation; much could be gained by supporting other developing countries such as Indonesia to do the same, although the surge in global demand for palm oil of recent years poses a major challenge for REDD+ - and for climate and biodiversity. What now? The next few days see the start of the ‘high-level segment’ of the UN climate talks, where ministers and heads of state arrive to flex their political muscle in the negotiations. This next week should be seen as an opportunity to bring forth practical and comprehensive steps forward in the lead-up to a potential 2015 agreement in Paris. Genuine progress can be made on the issues concerning climate finance, ambitions for mitigation, and loss & damage. It is clear that no big agreement will be reached in Warsaw, but this does not prevent it from laying out a solid framework to build upon in Lima, when the Parties meet next in 2014, and in Paris in 2015.

0 Comments

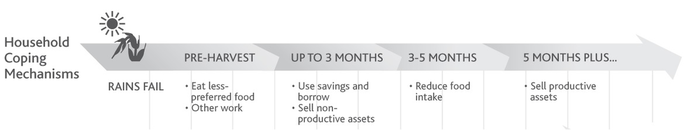

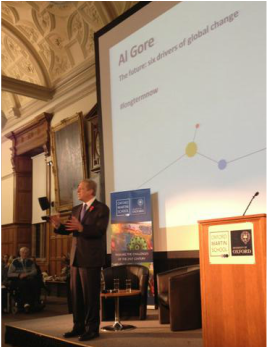

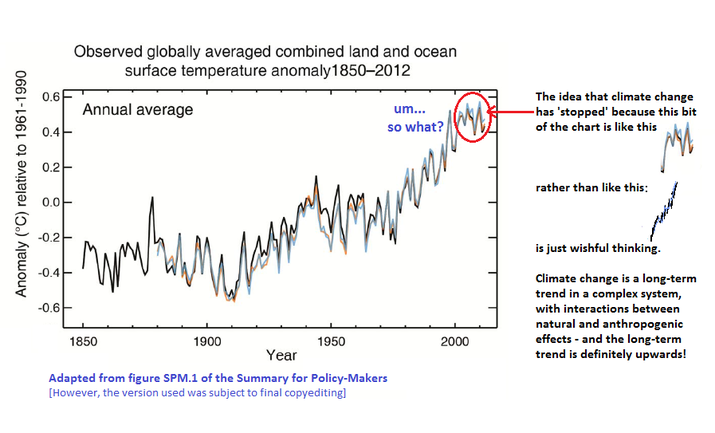

Gabriele Messori Typhoon Haiyan has dramatically brought the human cost of climate extremes before the eyes of the world. Here at the United Nations climate negotiations in Warsaw, the impact of the typhoon was echoed by a passionate speech from the delegate of the Philippines, Yeb Sano. In most geographical areas, climate change will lead to increasingly severe climate extremes. The nature of these extremes largely depends on the region of interest. While South-East Asia is prone to devastating typhoons, other regions are crippled by droughts. All these have devastating effects on public health, seriously compromising food security. There is therefore a strong need for an international mechanism addressing the losses and damage caused by climate extremes. A loss and damage agreement is currently being negotiated at the United Nations Conference of Parties, but the starting positions of many countries are radically different. While the developing countries push for a new mechanism dealing specifically with loss and damage, the developed countries speak of strenghtening existing mechanisms and bodies. Some countries, notably the U.S.A., also ask for loss and damage to be discussed in the framework of adaptation to climate change as opposed to as a separate mechanism. The question of liability for damage due to climate change is also a very contentious point. The U.N. negotiations are central to the matter, and need to provide a global coordination for tackling loss and damage. However, this does not mean that parallel approaches should not be developed. While the negotiations continue, the African Union has established a new specialized agency called the African Risk Capacity (ARC). The ARC is an extreme weather insurance mechanism designed to overcome the current ad-hoc disaster relief system. Countries will be able, by paying a premium, to insure themselves against drought-related damage. It is envisaged that the Capacity will be extended to other climate extremes in the future. The design of the Capacity and its current focus on droughts means that it has important co-benefits relating to public health. Research into household coping mechanisms has shown that droughts in Africa typically lead to a reduced food intake within a few months of the rains failing (typically 3-5 months, see infographic below). This can be averted if aid is received before this time. The objective of the ARC is for assistance to reach the designated areas within 120 days, meaning that the food security of the affected communities would be largely guaranteed.  Household coping mechanisms in the aftermath of a drought, courtesy of ARC. Currently, over 20 countries have signed the establishment treaty of the ARC. The mechanism will soon be operational, and has the full potential to become a leading example of international loss and damage mechanism. As with any project involving humanitarian assistance, the financial efficiency of the operation is crucial to its success. Projections indicate that the fast response mechanism on which the ARC is based would be over three times more effective per dollar spent than ad-hoc aid received after a crisis has unfolded. This is particularly true in those african countries where rain-fed agriculture employs a significant portion of the population. Regarding the scientific implementation of the project, the data collection is based on a satellite weather-surveillance system. An algorithm then translates the data collected into a risk and damage profile for each country, allowing for a precise value to be attributed to both the country's premium and its financial needs relative to a specific drought event. Currently, over 20 countries have signed the establishment treaty of the ARC. The mechanism will soon be operational, and has the full potential to become a leading example of international loss and damage mechanism.  Isobel Braithwaite Published in Outreach magazine at http://www.stakeholderforum.org/sf/outreach/index.php/previous-editions/cop-19/193-cop-19-day-3-climate-change-and-health/11583-climate-and-mental-health-impacts-and-inequalities The health impacts of climate change, and the importance of integrating health into adaptation planning, have become increasingly prominent in recent years - though arguably not prominent enough. For example, there have been several declarations from health organisations – the World Health Organization (WHO) has this year trained a number of Ministers of Health in climate policy, who are attending in their country delegations – and many adaptation initiatives now prioritise the health sector. Often the health impacts which are highlighted are things like heat deaths, malnutrition associated with food insecurity, changing distributions of infectious diseases, such as dengue fever, and the direct deaths and injuries caused by extreme weather events. All are important, and are likely to pose a significant threat to health – especially without an ambitious and equitable global deal, and successfully closing the pre-2020 emissions gap. What is less often considered, but equally important, is that climate change not only affects physical health but also mental health – and is likely to impact on mental health dramatically. It matters because of the immense detriment to people’s wellbeing, and because the other impacts of mental health are wide-reaching. There are knock-on effects on physical health and life expectancy, people’s ability to work and to participate actively in their communities, and of course on healthcare costs. After climate-related disasters such as floods, tropical storms and forest fires, affected communities have been documented to suffer rates of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many times higher than 'control' communities with similar socioeconomic conditions and baseline levels of mental health. For example, a 2001 study by Dr. Armen Goenjian and colleagues after Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua found that estimated rates of PTSD and/or depressive disorders in the worst-affected town of their study, Posoltega, reached 80-90%, compared to levels around a third as high in the least severely affected town, Leon. Slow-onset crises, such as those caused by droughts or sea-level rise, can also impact mental health adversely, and uncertainty about the future is a particularly important factor. At present the evidence base on the mental health impacts of disasters is sparse, because of the difficulties associated with conducting rigorous research in disaster contexts, the complexities and ambiguities that surround mental health in general, and the fact that – legitimately – research is not an immediate priority after a major disaster. However, the evidence we do have shows that the effects can last for months to years, and effective strategies exist to support mental health after disasters. This is of course a complex subject but evidence seems to suggest that the best approach is not necessarily to provide counselling for those affected, but instead to focus on resolving the main causes of distress, such as the need for shelter, social support and medical care, and in the longer-term, support to rebuild. The opportunity to rebuild elsewhere, or to migrate, can also be important, including to reduce future risks, and can be a form of adaptation – especially for those affected by sea-level rise or desertification for instance. This issue has not yet been adequately addressed by the UNFCCC framework or other international institutions. Mental health is already a major challenge in global health today, and it is rising. By creating the concept of a 'Disability-Adjusted Life Year' (DALY; comprised of years of life lost and years lived with disability, where weights are applied), the Global Burden of Disease project has enabled us to compare a wide range of conditions in terms of ‘healthy life years lost,’ including those which are generally non-fatal, such as mental health conditions, into priority-setting. According to the latest assessment in 2010, major depressive disorders have risen to become the second highest cause of DALYs lost worldwide; anxiety disorders are close behind. In both women and younger age groups, both rank higher still. Both are also particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, particularly in the poorest communities: climate change creates a doubly uneven playing field for women’s and young people’s mental health. We also know that the levels of mental distress and conditions such as PTSD seen after disasters are influenced by factors such as the severity of the event, the damage caused, the existence of effective relief systems, and access to funds to enable people to rebuild their homes and for communities to recover. As well as strengthening the case for investment in adaptation, this is highly relevant to the ongoing discussions around Loss and Damage at COP 19, and – as the science of climate change grows stronger; the task of mitigating it ever more urgent – it is essential that wealthier countries, who have benefitted from their early industrialisation, support those who have contributed least to climate change to cope with and recover from its’ impacts. More references and links: http://climate.adfi.usq.edu.au/statements/74/  Loss and damage highlighted on the first day at UN Climate Talks Tim Dobermann, Healthy Planet COP19 delegation "I will voluntarily refrain from eating food during this COP until a meaningful outcome is in sight,” announced the Philippine lead negotiator Yeb Sano today. This was in the opening session of the 19th Conference of the Parties (COP19) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Warsaw, Poland. Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest typhoon on modern record, slammed into the Philippines and much of South-East Asia late last week. So far, anestimated 10,000 have died, but it is likely that the final toll will increase as the Philippines cleans up the destruction left in the typhoon’s wake. In the opening session, Mr. Sano gave a passionate plea for us to “open our eyes to the stark realities we face” and to come together to make significant progress on a global deal covering mitigation, adaptation and finance for developing countries. Devastating storms like this are becoming more common. We cannot attribute a given extreme event to climate change with certainty, but they form part of along-term trend of more severe storms, heatwaves, floods and forest fires, and are consistent with the IPCC's predictions.

On the other hand, many developed countries are worried that loss and damage payments could easily spiral out of control, and that they may weaken incentives for countries to invest in adaptation efforts. Both are probably correct. Loss and damage – an issue that has only very recently emerged on the negotiating scene – will require an international body to determine the extent of losses as well as to spread reparation responsibilities in an equitable manner.

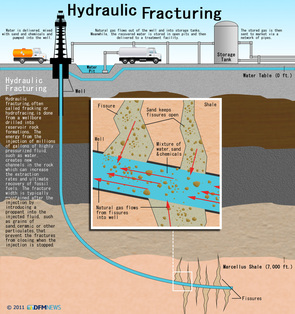

Much of this year’s climate negotiations will be focused on establishing the framework for a post-2015 deal, designed to be agreed upon when countries meet in 2015 in Paris. In this sense, there may not be many ‘big outcomes’ from the negotiations. However, given recent events and a considerable degree of attention, there is potential to make rapid progress on loss and damage over the next two weeks. Having been fortunate to call the Philippines home for 16 years, it truly saddens me to see this continual suffering. Mr. Sano fully embraces his role not only as a diplomat or a proud Filipino, but as a representative for all of those on this planet who will directly feel the effects of climate change. The human cost of climate change is real, and it has never been clearer. It is a shame that we are in a situation where Mr. Sano needs to resort to a hunger strike to communicate the seriousness of these issues. All of society – NGOs, governments, the public – must take this message and respond. I hope that we will remember these next two weeks as the time when a brave man took a stand, to which we, finally, responded. By Connor Schwartz  Emissions rights. Who deserves the biggest slice? Emissions rights. Who deserves the biggest slice? In part one we laid the groundwork of theory upon which to build a climate regime which recognises the entitlement of all to the dignity and respect of a life that is fully human. Now I would like to begin to flesh out what such a regime demands of our approach to climate change and our distribution of the burdens associated with solving it. First of all, health. Although not indexed, it is clear that health is one of the most vital capabilities we are entitled to. Climate change has far reaching distributive effects for global health if we choose to do nothing, but so too do our possible attempts to mitigate and adapt to it. The messages from Sen and Nussbaum are clear. Allowing climate change to continue unabated will harm our entitlement to adequate health gained by our species membership, therefore seriously contravening the demands of justice. Furthermore, the way we respond to climate change must be in accordance with the promotion of global health to all of the world’s people and not to the detriment of it. Sounds just so far. Secondly, emissions allocation. GHG emissions, if we are to mitigate the effects of anthropogenic climate change, are a resource and therefore must follow a distribution. We can think of the “safe level” of emissions that we can emit and still prevent runaway climate change as a huge cake. This cake is thought to have been about 1 trillion tonnes in 2009, in order to remain below a 2 degree warming on pre-industrial levels. Mmmm, delicious emissions cake. Well one of the key jobs of the UNFCCC is to divide up that cake while all the countries of the world ask hungrily for a decent slice. Under a capabilities analysis, the current distribution of the cake has got to change. At the moment, people in Australia, the USA and Europe scoff their slices while driving SUVs, eating meat and jumping on short haul flights. Meanwhile, those in the developing world cannot scrape together the crumbs to industrialise their domestic agricultural practices and ease food security crises. This contravenes seriously the demands of justice. I think we can go further still. I would argue that the costs of mitigating and adapting to climate change should be distributed according to the levels of emissions that have not been used to secure basic capabilities. Since we are each entitled to our basic human capabilities, we can lay no blame for emissions used to provide decent healthcare, adequate education, ensure the empowerment of women, secure equal political rights, etc. We can lay blame, however, for emissions used to provide luxury while the planet plunges into climate crisis. One final point on capabilities for any who are still with me. Any distribution found in a climate change regime, and there are many, seems appropriate for analysis as a distribution not of the resource but of human capabilities. Any, that is, except for one. As the effects of climate change begin to come about, and the extent of the effects we have already “locked in” to our climate system are realised, an area of growing importance is compensation for negative effects – known as “loss and damage” within the UNFCCC. This area of negotiations is likely to be a significant part of the focus for COP19 just around the corner, and a main focus for NGOs in attendance. So what to make of loss and damage within a capabilities framework?  The explosion of climate refugees is a tragedy beyond measure. The explosion of climate refugees is a tragedy beyond measure. It is hard to reach any conclusions at all. Recall that the cornerstones of the approach were that human goods were neither aggregable nor fungible. That we just can’t make sense of capabilities having a value in terms of anything other than themselves. Financial compensation for the loss of capabilities does not a just situation make. They are simply qualititatively different. The most we seem able to say is that the situation in which someone is forced from their own environment by environmental factors caused by those on the other side of the world is unbelievably tragic and should never have happened. Although undoubtedly true, this expression of sadness doesn’t seem of any practical use when faced with the reality of millions of climate refugees, of the loss of political freedoms as resource wars are waged, and of backsliding in gender equality when female-dominated industries such as agriculture suffer in the hands of climate crisis. Well then, what else can we say? We can say that compensation paid to nation states without directions on what the money is for is morally wrong. It doesn’t matter how many millions we give to Bangladesh for their climate damages, if there are people without replacement homes that they feel comfortable and safe in then justice has not been served. Any lost capabilities therefore must be compensated for in kind. For example, environmental refugees must be provided property rights on an equal basis with others in the countries in which they settle, and political rights to have an equal say in how they are governed. Those whose diets are disrupted by the effects of climate-related extreme weather events on agricultural yields must be recognised as having an entitlement to the provision of adequate nutrition as a minimum requirement of justice. So, all in all, this is just one approach at a robust theory of climate justice and just one provision for a just climate regime. Fundamentally I think, if imperfect, it starts us down the right track. We must recognise that climate change not only has the potential to exacerbate inequalities when left unchecked, but also when solved inequitably. We must refuse to equate human good to a monetary value and reject the politics of self-interest. We must recognise the entitlement of all to adequate health, and the dignity and respect of a life which is fully human. There is no reason why my answers are more valid than yours, but it is vital that we keep trying to provide them and never fail to ask the questions. We have a colossal challenge ahead of us in mitigating, adapting to, and compensating for anthropogenic climate change. But we must embrace justice as we move forward. The wrong solutions threaten to do as much damage as none at all. By Connor Schwartz  Amartya Sen ponders justice Amartya Sen ponders justice Climate ethics and climate justice are subjects which hide in the background of COPs and treaties, rarely given any limelight of their own. In fact, the most common appeal to climate justice within negotiations are false ones, nations setting out their stall while grasping furiously for some foundations to stand it upon. Because, while the neoliberal hegemony of self-interested actors fails miserably to encompass the breadth of human social relations, it is demonstrably accurate on an international level. Powerful nations may appeal to political theory and forms of justice to back up their positions, but you can bet that their move went outcome first, evidence second, and not the other way around. For example, in the early 2000s while America was resisting becoming party to the Kyoto Protocol, the Bush administration argued furiously that the Annex 1 countries were being unfairly asked to mitigate a crisis which, all things considered, it looked like other countries had a lot more to lose from than themselves. Slowing anthropogenic climate change will cost us a packet and only benefit Tuvalu, how unjust! It did not matter, of course, that this claim is justified only by a philosophy so libertarian that no US president (Nixon included) has ever come close to it. No, much more important to scream “injustice!” and hope nobody really notices that the argument doesn’t stack up. Thus climate ethics has been sullied and debased by negotiators wanting a transcendent justification for their greed. It’s time to put it back at the heart of a global climate regime. Here is just one such attempt. It’s not perfect but I think it reveals a few key things we are looking for from a global climate treaty, and provides the beginnings of a move away from pragmatism and towards justice. Hold tight, here comes the theory. (If you’re not interested in the theory in isolation, jump straight to part two where climate change comes back onto the scene). When we discuss distributive justice of any kind, the first thing to be argued over is what’s called the “metric” – what exactly it is we should be distributing. Let’s narrow our gaze to egalitarianism – that equality is, for some reason, at least partially good – as it is now almost universally accepted across the liberal democracies. There are two traditional camps in the metric debate: resourcists and welfarists. As their names give away, resourcists believe justice includes a focus on equalising the amount of stuff people have, whereas welfarists prefer a focus on the wellbeing or happiness people get from that stuff. It’s the classic means/ends debate. This division has been standing for hundreds of years, splitting radical feminists from their traditional colleagues and communists from conservatives. This impasse however was, I believe, broken in 1979 when Amartya Sen – a heterodox development economist from Bangladesh – gave his Tanner Lecture entitled ‘Equality of What?’. In this lecture Sen dismantled both metrics, each with a simple thought experiment, asking whether what each model was forced to conclude sounded much like justice or not. Number one. Take two agents: one able-bodied and another with a severe disability needing round the clock care. Equalise resources. After covering their care expenditure, the disabled agent has far less resources than the able bodied agent to increase their wellbeing with. Similarly other divides – gender, social position, country of birth, etc. – reach the same conclusion: that a resource egalitarian looks to be saying that justice permits, or even requires, that wellbeing is determined by factors of luck. Ask yourself: does that sound much like justice? Number two. Brian is a plumber living in the city of London and Vikram works as a dabbawalla, distributing Tiffins to the workforce of Mumbai. Brian, from any objective standpoint, enjoys a far higher standard of living than Vikram yet it is certainly conceivable that Vikram is the happier of the two. Empirically, what’s called “hedonic adaptation” shows us that as our income increases so too can our expectations, resulting in no greater happiness. So say Vikram is the happier of the two because he expects less, and we have some spare resources to distribute. We must be persuaded to give the extra to Brian. Justice? To say a poor person has no claim to extra resources because their expectations are lower doesn’t sound much like justice to me. So what does Sen suggest? Justice, he claims, is found in neither resources nor welfare, but some function between the two, some measure of how we can translate resources into welfare. The correct metric for distributive justice is a person’s capabilities or, to be specific, the capability to achieve particular substantive human functionings. Say what? Put simply, what justice demands is equalised are the real and tangible freedoms that humans can possess. It doesn’t matter how much income a person has, if they have no access to healthcare then they are not being served by justice. It does not matter how happy a person is, if they cannot access education then that is a failure of justice.  Martha C. Nussbaum Martha C. Nussbaum Although the language of capabilities was introduced by Sen, it was American theorist Martha C. Nussbaum that developed it into a robust philosophical doctrine. Borrowing from the young Marx, Nussbaum claims that justice provides entitlement to a plurality of values that are both non-aggregable and non-fungible. In other words, we cannot serve justice by simply giving all a certain amount of a certain thing – say, money – and then leaving them to make choices as to how they trade it. Rather, we must concentrate on fulfilling a range of indicators that are distinct and cannot be traded off against each other. Simplistically, one could not for example be compensated for an inadequate life expectancy by being allocated more political rights. This stands explicitly against classical and neoliberal theories of development, relying on GNP to assess the growth of a nation and the wellbeing its peoples. What’s more we do not have to earn these entitlements. They are derived from our entitlement to “the respect and dignity of a life that is fully human”. We possess them, therefore, merely due to our species membership. (Nussbaum also holds that it is likely many other species are similarly entitled to various capabilities, but for now we can just consider our entitlements on account of our being human.) That’s all well and good, but what on earth does it have to do with climate negotiations? Lots, actually. Part two focuses on bringing climate change back into the picture, and putting justice back at the heart of a global climate regime.  Tim Dobermann, Healthy Planet COP19 delegation Have we reached critical mass - a global tipping point - in the climate debate? If not, just how long will it take for the world to act on climate change? Not long, said Al Gore on Thursday during his Distinguished Lecture for the Oxford Martin School. Citing the civil rights movements in the mid-20th century, and more recently, the sharp turnaround in public opinions over gay marriage, Gore spoke of the significant role movements can play in spurring national and international action. More importantly, he spoke of how - once reaching a critical level of public attention - these issues rapidly exploded onto the political scene, with reforms following soon after. Our role in shaping the Earth's climate is now beyond question, and the world's leading Earth scientists have laid out what a safe operating space for humanity looks like - and the areas in which we are transgressing those boundaries. However, our responses have been muted; timid, at best. Climate change is an incredibly complex issue. It spans many disciplines and concerns all aspects of our society: economic, political, social, moral and ecological. Only until recently have serious efforts been made to communicate these effects to the public. Fundamentally, we need a change in mindset about how we view the way we interact with our planet and its ecosystems. We must recognise that, like all species before us - and all species after us - we are dependent on nature for our survival and well-being. Al Gore draws hope from the fact that all successful movements in the past had one link in common: despite their inherent complexities, they quickly evolved into a simple decision over what was deemed right and what was deemed wrong. It is wrong to segregate or discriminate against people based on the colour of their skin. It is wrong to outcast individuals for their sexual orientation. Now, more than ever, it is wrong to recklessly continue polluting our oceans, ecosystems and atmosphere, damaging our health and placing increasing strain on vulnerable households across the world. Out of a formidable list of factors that will drive our future - rapid globalisation of economic activity, information technology continuing to connect our world, and inequality pulling our societies apart, amongst others - Gore is not hesitant to declare climate change the largest single driving force of our future.  The aftermath of the 2010 Pakistan floods. Image source: LA Information The aftermath of the 2010 Pakistan floods. Image source: LA Information It's no surprise why. Though the impacts of climate change will not be distributed evenly across the globe, climate change will change what we view as normal - and to an extent it already has. Extreme weather events like the unprecedented European heatwave of 2003, with an estimated death toll of 70,000, or the heavy flooding in Pakistan in 2010, which displaced over 1.5 million from their homes and adversely affected millions of others, are projected to become much more common. But the effects of climate change on our health and well-being extend far beyond extreme weather events or storms. As the 2009 UCL/Lancet Commission 'Managing the Health Effects of Climate Change' highlighted, often overlooked are the indirect health impacts: water scarcity and more variable rainfall leading to food insecurity and malnutrition, droughts breeding conflict and unrest, or the mass displacement of populations -`environmental refuguees' - out of desperation. To prevent catastrophic warming, and to avoid further harm to those least responsible for the emission of greenhouse gases, we must usher in a new era of widespread ecological sustainability. Gore, in a sincere display of passion, ended with a final anecdote: a memory of him as a child, aged 13, listening to John F. Kennedy's famous words on challenging the nation to send a human being to the Moon and back. Many said it wasn't possible; it was too expensive; it just wouldn't work. Eight years later, in 1969, the world held its breath as humans took their first ever steps on the Moon. Euphoric, the team at NASA headquarters burst into cheers and applause. At the time, the average age of the NASA engineers in the room was 26. This means that, eight years earlier when Kennedy challenged the entire nation, they were only 18. This story couldn't better reflect how the young people and students of today can - and should - play an active role in shaping our future. With dedication and determination, we can play a tremendous role in ensuring that we establish a safe, just and sustainable operating space for humanity.  Isobel Braithwaite The Healthy Planet delegation & support team for COP19 are having a twitter chat to discuss the recently released summary of the IPCC's 5th Assessment Report (Working Group 1) - you can download the summary of the IPCC AR5 summary here and more info on how we're planning to structure the chat here. The report is all about the climate science and includes projections of future temperature change, sea level rise and a discussion of other areas such as effects on oceans and air quality - and it makes for pretty depressing reading given the lack of significant action by governments, corporations or individuals, and George Osborne's cowardly and backward-looking stance that the UK shouldn't lead on climate change. The science and the inaction combine to create a lot of pretty worrying implications for health - but there is a good side too since there are many ways in which sustainability can benefit health - for example through active travel policy, clean energy and well-insulated homes. The section on human health is being released next year, and will be an update on the human health section from Assessment Report 4 in 2007 (available here). TIME magazine recently had a good piece on 'rebranding climate change as a public health issue' which highlighted some of the main impacts of climate change on health, and the scope for much greater impacts in the future. It showed how these aren't only in developing countries, although often the impacts are worst here - due to people's greater vulnerability and more limited opportunities for adaptation - with the example of Hurricane Sandy. At the same time, somewhere like New York is much better prepared and able to cope than, say, Tuvalu or Bangladesh. With rising sea levels and more evaporation, extreme weather events like Sandy are expected to become more frequent and more intense under climate change, as with flooding in general. Not only are there physical health consequences to events such as this, with potentially contaminated drinking water, exposure to cold and damp, reduced access to healthcare etc, but the mental health consequences of being displaced and losing property, and sometimes loved ones, can be immense and long-lasting. But climate change also affects health in more chronic ways, for example through long-term reductions in many regions' capacity to grow food because the growing temperatures are too high, and on top of this the effects of droughts, floods and the spread of crop diseases and pests to new places. Similarly, sea level rise, which is predicted to be at a faster rate and to reach 26-82cm higher than now by 2100, could force millions of people to migrate and increase the risks of coastal flooding and storm surges, causing loss of life directly as well as indirectly, eg. through crop losses and the spread of diseases like cholera and malaria. It can undermine people's livelihoods and contribute to migration and conflict, putting even more lives at risk, although typically this is in conjunction with many other drivers and near-impossible to attribute to climate change.  What about the 'hiatus' or 'pause' in warming that many skeptic groups are going on about and arguing is a sign that climate change won't continue? A recent article in Nature by Quirin Schiermeier quotes a co-chair of the report, Swiss climate scientist Thomas Stocker, at the launch of the report talking about the hiatus. According to Stocker, 'Comparing short-term observations with long-term model projections is inappropriate. We know that there is a lot of natural fluctuation in the climate system. A 15-year hiatus is not so unusual even though the jury is out as to what exactly may have caused the pause." It appears that deep oceans are taking up a lot of the excess energy that's being trapped, but Stocker's point that this is about long-term trends - and the last decade was the warmest on record - is important. Moreover, the real question is - do we need to be certain of something not to want to take that risk with future generations' health. We only have one planet and if this were and experiment, we'd never allow it. David Mitchell has a brilliant soapbox piece on this very topic (see below, worth a watch! And please ask us your questions and share your thoughts with us!! You can get in touch at [email protected]  Alistair Wardrope, Healthy Planet Sheffield Originally posted here Would anyone dispute that healthcare systems ought to put their patients first? The mantra has a near-unassailable status in discussions of the best foundations for healthcare. The UK’s General Medical Council makes it first amongst the Duties of a Doctor; it provides the title of the Department of Health’s response to the findings of the Francis Report; and it lies (in its more-theorised form, ‘patient-centred care’) at the core of Don Berwick’s recent report into safety in the NHS. No politician, of any political stripe, would see fit to enter into a debate on health without it taking pride of place in their rhetoric. I’ve used it myself, campaigning for the priority of “patients before profits”. Nonetheless, I’ve long had qualms about it. It took a work of fantasy to figure out exactly why. During a recent and all-too-brief summer break, I decided to read China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station. I had harboured the vague intent of doing so for several years, but a fortuitous alignment of stars and an inability to access the books I was supposed to read in the university library meant I finally did. As a (somewhat lapsed) devotee of speculative fiction, I’d always expected to find more than simple escapism between its covers; however, I did not expect it to form the nucleus around which those nagging worries about patient-centred care would crystallise. The passage that set me thinking is little more than an aside, one of the short conversational detours the novel is littered with. It concerns a society of nomadic bird-people, the Garuda of Cymek. Garuda society is founded on the moral and political primacy of individual freedom. Their legal code admits but one crime – depriving another Garuda of choice; their ethical code, only one vice – disrespect. So far, so Tea Party. But the Garuda take these principles in an altogether different direction. Their interpretation of individualism rests on a particular understanding of what the individual is: the ‘concrete’ individual. As Ged, the autodidact librarian-priest, states: You are an individual inasmuch as you exist in a social matrix of others who respect your individuality and your right to make choices. That’s concrete individuality: an individuality that recognizes that it owes its existence to a kind of communal respect on the part of all the other individualities, and that it had better therefore respect them similarly. With the individual understood in these terms, disrespect becomes at heart a crime of ‘abstraction’: isolating one’s own individuality from the network of social interactions by which it and other persons are constituted and so losing the symmetry between them in which equal status is grounded. The Garuda share their ‘concrete’ understanding of the individual with a strong line of philosophers and political theorists. In his influential essay ‘Atomism’, the communitarian thinker Charles Taylor describes the individual as existing only when grounded in a society that affords the material, psychological and social resources for them to develop into freely-choosing agents, and provides the range of options necessary to make such choices meaningful. Respect for such individuals, therefore, is inseparable from respect for the social conditions underpinning their individuality. This is in stark contrast to the ‘atomism’ of the title, a charge he levels against the libertarian individual, whose values and preferences are interpreted and realised independently of others, and the protection of whose choices sets the boundaries of an acceptable social contract. These ideas are developed upon in recent work in feminist philosophy on ‘relational’ conceptions of autonomy. Traditionally, medical ethics has employed a rather thin understanding of autonomy – interpreted in the doctrine of informed consent, for example, as little more than decision-making capacity. Relational theorists argue that this ignores the role played by our emotions and attitudes towards ourselves and others – and their attitudes towards us – in developing and maintaining our capacities for autonomy. Consider an individual who, after a lifetime of oppression, comes to adopt those oppressive values as his own; the individual who does not have the necessary self-respect to consider herself worthy to make her own; or the individual who, like Aesop’s fox rejecting the inaccessible grapes as sour, comes to view certain ways of living as undesirable only because they are not realistic options available to them. In each case, the individual may be in full possession of the faculties that constitute mental capacity, but faces more subtle, relational, threats to their autonomy. The concrete individualism of the Garuda – and the work of communitarian and relational theorists – captures my concerns about patient-centred care. For in many interpretations of the term, the idea of the patient upon whom care is being centred is what the Garuda would consider an abstract individual. When patient-centredness merely means enhancing patient choice, increasing medical consumerism or a way to promote marketisation of health services, we present the patient as the isolated, rational ‘chooser’ that is the subject of Taylor’s ‘atomism’ critique. More generally, an interpretation of patient-centred care focussed solely on the clinical encounter – where it concerns only the interactions between health professionals and the individuals who come to them at the point of clinical need – risks leaving out other individuals and important aspects of care. When care is centred on the patient, who or what falls into the periphery? It seems to me that many who fall into the margins of this picture are those who are already most marginalised. Most obviously entering into this group are those who need health care but are unable to access it: ‘patient-centred’ care, focused on the abstract patient, has nothing to say about caring for those who – through legal, economic, social or psychological barriers to access – are unable even to become patients. But, even setting aside the tremendous injustice and inequity – where the most vulnerable communities, such as vulnerable migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, poor and oppressed groups, are done further harm –ignoring these groups is a public health disaster. Perhaps this could be remedied by defining ‘patients’ according to their need for health care rather than their ability to access it; but this picture still sees those patients as abstract individuals, and so has little room for public and global health concerns that make no sense in individualistic terms. Infection control, mitigation of climate change and its health impacts, social and political action on the social determinants of health: all are relational public goods. They are not focussed toward, or done in aid of, any individual patient, and only make sense at a population level. In the current political climate in the UK – where attempts are being made to limit access to healthcare for migrants, and such care is increasingly conceived of as a service provided to individuals for individual benefit – the rhetorical use of patient-centredness emphasises only the abstract patient, with the attendant dangers to public health sketched above. But the good news is that, when the individual is understood in concrete terms, these dangers are not just brought back into the fold – they become a central component of patient-centred care. The reason why is simple: the health of the individual simply cannot be considered in isolation from that of the population. As Sir Muir Gray writes, “personalised and population medicine are interwoven like warp and woof.” A healthcare intervention is never solely for a single, isolated patient; it is simultaneously a public health measure. So when the International Association of Patient Organisations puts patient involvement in social policy, universal access to health care, and attention to education, employment and family issues at the core of its definition of patient-centred care, it is not adding these in as an additional ingredient to aiding execution of the interests and desires of individual patients in the clinical setting. Rather, it acknowledges the former as a core component of the latter. And protecting and extending access to healthcare for migrants – economic, asylum seeker or undocumented – is not a good to be weighed against the health needs of a nation’s citizens, but an integral part of serving those needs. In meeting the challenges of shaping more environmentally sustainable health systems – able to meet the needs of people today without sacrificing those of future generations – we need not marginalise or ignore current patient’s interests; as elsewhere in healthcare improvement, “the greatest untapped resource in healthcare is the patient.” Such work on sustainable healthcare – the focus of this September’s CleanMed Europe conference in Oxford – is a re-interpretation of what patient-centred care could be, modelled on a more comprehensive understanding of what it means to be a patient. It turns out, then, that my concern is not primarily with putting patients first, or with patient-centred care – at least, not with what those ideals could and should mean. The problems arise only when the individual is considered in isolation from their social and political context and the environment around them. Given the fundamentally relational nature of health and disease, this isolation is intellectually and ethically untenable; patient-centred care makes sense only when we listen to the lesson I was taught by a fictional society – to view patients (ourselves included) as concrete, inherently social, individuals.  Emily Collins, medical student at Keele University If you’ve seen the news recently, you’ll probably have heard many loud opinions battling to have their say on fracking. Fracking is a process that is unfamiliar to most of us, but which could have big effects on our world, depending on who you listen to. So what is it? And why is it such an important issue? Fracking (hydraulic fracturing) is a feat of engineering aimed to increase the yield of natural gas gleaned from the earth, in order to be used as fuel. As a fossil fuel, formed when marine plankton and ancient plants trapped sunlight energy and carbon over millions of years, natural gas is an unsustainable energy source and burning it produces carbon dioxide. Drills dig deep into the earth, vertically then horizontally, while pumping in water and chemicals at high pressures to open up fissures in the shale rocks way down deep: this frees trapped gases. These are then captured and piped off at the earth’s surface, ready to use as fuel (helpful video: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-23320540.) Having been widely used across the US, the government has recently announced the lifting of a temporary ban of fracking throughout the UK which has sparked controversy and protests, such as those in Balcombe and elsewhere. Why the enthusiasm? Hard to reach oil and gas can be accessed by fracking. It has been estimated that there is as much as 1,300 trillion cubic feet of shale gas underneath the UK – a tenth of which, if extracted, would be the equivalent of 51 years’ gas supply. (1) There are two main possible benefits: first, UK gas prices could be driven down, as they have been in the US. This could be a big boost in the days of our troubled economy, where many families struggle with meeting the rising cost of energy bills – but as this letter to the FT from a senior (republished here) explains, even using very optimistic assumptions only investors in the extraction companies and the Exchequer are likely to benefit, unless gas imports are penalised. At the same time, the cost of solar panels has dropped 80% due to a surge in Chinese production. Is it really just a coincidence that Osborne’s father-in-law is an oil and gas lobbyist?  From an environmental perspective, electricity can be generated from natural gas at half the CO2 emissions of coal (potentially at least) so, compared to coal it could plausibly be a step in the right direction. But there are big question marks on wheter this is true – see below – and is coal really the benchmark we should be using in 2013? Another potential benefit of fracking – especially in the context of today’s record unemployment - is the creation of jobs in Britain. David Cameron claims that as many as 74,000 jobs could be supported by the growth of this industry (1). If true, this would be hard to overlook, although many of them would be temporary. But the job creation argument applies just as strongly to investment in the green economy, as the Green Is Working campaign and this report from the Green Alliance show. Even if realised, the benefits of fracking come with big risks, and could cause lasting damage to our planet and our health. Water usage and chemical contamination Fracking uses huge amounts of water – just one site requires millions of gallons of water. This will compete with water resources in areas which are already prone to and experiencing shortages, areas which are also expected to increase with climate change. Transport of these large volumes of water to and from fracking sites will also have environmental impacts. In addition, there is serious public health concern about the risk of water quality being affected, with a concern that carcinogenic chemicals such as benzene, toluene, xylene etc among many others, used in the water will leak and contaminate groundwater around the site. Earthquakes There are concerns that fracking can cause earth tremors. In 2011, two small earthquakes occurred in Blackpool following exploratory fracking. Several reports have been conducted into the matter and it remains possible that future fracking will lead to some tremors. However, a recent report from the Department for Energy and Climate Change claimed that the risks of structural damage from these tremors remain low, and the process has been given the green light, albeit with stringent regulations.  Climate change The science is telling us that we really need to keep most remaining fossil fuels in the Earth if we want to avoid catastrophic climate change, as highlighted by Bill McKibben's Do The Math talk (coming to the UK this Autumn in a 'Fossil Free' tour coordinated by People and Planet!) In that context, is fracking just a distraction from developing renewable sources of energy? Cameron, like Osborne, says ‘we’re not turning our back on low carbon energy’ - just using fracking to help meet our energy needs – but we could do that with sustainable energy too. Does the move just encourage continued dependence on fossil fuels, ‘one last fix’ before we change? As Friends of the Earth’s Head of Campaigns, Andrew Pendleton, said in reaction to the 2013 Budget: "This is yet another fossil-fuelled Budget.... Our economy desperately needs new ideas, but George Osborne is a 19th century Chancellor, using 20th century tools to fix 21st century problems". Natural gas is mostly methane – which is over 20 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 – and it has been found to leak from fracking sites in quantities much larger than originally thought. Burning fracked natural gas is only a greener alternative to coal burning so long as gas leakages into the environment are kept to a minimum, specifically below 2%. Studies predict, however, that leakages may be significantly higher, with a recent study in Utah finding a leakage rate of 9%. A New Scientist article published yesterday cites that if rates are around 10%, at the top end of estimates for the US, then the escaped gas would increase global warming until the mid 22nd century. The climate is a very complex thing: the same article also notes that side-products of burning coal, sulphur dioxide and black carbon, actually cool the climate to some degree and offset some of the warming created by the production of greenhouse gases – although they also have negative health effects. There’s a lot to consider when it comes to the debate about fracking. What damage to our planet is too much? Will fracking really be the solve-all economic miracle the government is claiming? The debate is open – what do you think? |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed