CLIMATE CHANGE, MIGRATION, AND HEALTH

|

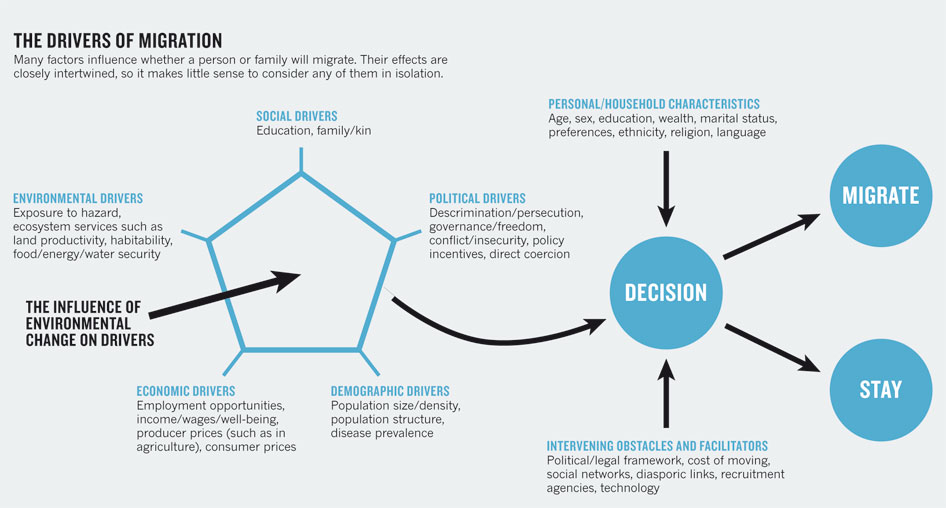

While there is widespread consensus that climate change is fundamentally reshaping the distribution of communities both within and between countries, it is less well understood what mechanisms are most prominent in determining this redistribution, how climatic variables interact with other factors affecting migration, or whether it even makes sense to distinguish 'environmental migrants' from other migrant populations. While few would argue that 'environmental migration' would cover people from small island states in the Pacific whose homes are claimed by rising sea levels, what of farmers who choose to move to urban areas as climatic pressures reduce their harvests and the economic viability of their operations? And what of refugees fleeing violent conflicts exacerbated by climatic stressors?

However one defines the specific details, climate change is already causing, and will continue to cause, migration - permanent and temporary, internal and international. Forced displacement is associated with a range of detrimental health impacts, arising from conditions leading to displacement, the migration journey itself, and conditions on arrival at migrants' destinations. These factors themselves - and the stability of recipient communities and capacity to adapt to new populations - are themselves vulnerable to climatic factors, further complicating the intimate relationship between climate change, migration, and health. Explore more below. |

Key points

|

Environmental migration - causes and varieties

In the words of the International Organization for Migration, climate change and migration comprises a 'complex nexus' - linking two such diffuse processes, dependent on a range of physical and social variables, necessarily becomes a somewhat messy topic; the political sensitivity of both subjects adds a further layer of controversy to complicate matters. The IOM uses the following as its working definition of environmental migration:

"Environmental migrants are persons or groups of persons who, for reasons of sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affect their lives or living conditions, are obliged to have to leave their habitual homes, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their territory or abroad."

|

Thus the term encompasses those who are forced to leave their homes due to their disappearance or destruction, or being otherwise rendered uninhabitable. But it also covers those who are forced temporarily to leave because of a natural disaster; those who gradually witness their environment becoming progressively less able to support their living (or less profitable than alternatives elsewhere); in short, those who want to migrate for all the reasons historically and presently humans have moved across the earth - where those factors are in part influenced by a changing environment. As with the many health impacts of climate change mediated by social systems, environmental factors act as a 'threat multiplier' for already-existing problems, where the effects will be most pronounced in social structures that are already fragile for other reasons.

|

A recent Foresight Report commissioned by the UK Government outlines some of the range of environmental stressors leading to forced displacement and migration across the world:

Equally important - though less high-profile - is how climate change may also impede migration, or social failures may prevent people using migration as a climate adaptation strategy. This may arise acutely - as with armed conflict in Somalia preventing movement, or in New Orleans where inter-city transport networks relied so heavily on motorised transport that the federal evacuation plan assumed everyone would have a car. But it may also come from slower processes, with increased economic hardship gradually undermining households or communities' ability to relocate.

- In Bangladesh, 22% of households affected by tidal surges and 16% facing riverbank erosion move to urban areas

- Temporary labour migration in Kenya is 67% higher in households farming land with poor-quality soils

- Many Pacific island states are already making plans for when and how they will relocate when their present territories become uninhabitable

Equally important - though less high-profile - is how climate change may also impede migration, or social failures may prevent people using migration as a climate adaptation strategy. This may arise acutely - as with armed conflict in Somalia preventing movement, or in New Orleans where inter-city transport networks relied so heavily on motorised transport that the federal evacuation plan assumed everyone would have a car. But it may also come from slower processes, with increased economic hardship gradually undermining households or communities' ability to relocate.

Environmental migration and health

|

The different varieties of environmental migration and the different factors relating to different migration journies and destinations mean that environmental migration and health are linked by diverse mechanisms. The impacts can be negative, but may also be positive - researchers increasingly stress the importance of migration as a climate change adaptation measure.

Those most likely to suffer from acute ill health effects related to climate-induced migration will be those forcibly displaced from their homes by environmental events like natural disasters or conflict. Such events force vulnerable population groups (young children, the frail elderly, people with chronic illnesses) to undertake arduous journeys, deprived of basic necessities for good health like food, water, and shelter from the beginning, with their destinations often being developing regions lacking the redundant capacity in social support systems to host an influx of people. Forcibly displaced people are at increased risk of infectious diseases from unhygienic and overcrowded living conditions and food or water contamination. They often suffer from under-nutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. Lack of maternal and perinatal care provision greatly increases the risks of childbirth and the neonatal period. And they suffer from vastly higher rates of mental illness, particularly PTSD, anxiety, and somatoform conditions. |

Recording of a seminar on climate change, migration, and the role of health professionals, held at the Royal College of Physicians in June 2015

|

The health risks of forced displacement are greatly exacerbated, and new risks added, by ill-conceived policies in recipient states. Forced detention of migrants is common across the world, but has a range of deleterious acute and chronic mental health impacts, particularly for children. Barriers to work and poor accommodation provision expose men, women, and children to sex and gender-based violence. And not only do border closures and other arbitrary restrictions to movement encourage people to take more dangerous journeys, they also prevent people using migration as an adaptation strategy, trapping them in environments highly vulnerable to climate threats.

|

|

The association between climate change, migration, and health is also found in other forms of environmental migration, though the connections here are often more subtle and the evidence sometimes less clear. Economic migration (due e.g. to drought-related crop failure) - often to urban areas - carries with it a host of associated risks. This migration may in fact expose migrants to greater climate risks - for instance when people move to cities like Dhaka or Lagos, built on floodplain. Migration patterns to cities such as these is predicted to result in an explosion of people exposed to flood risk - for example, 40% of recent migrants to Dakar in Senegal live in areas of high flood risk. Such rapid population expansions are also linked to increasing social and political tensions, weakening social support systems and even resulting in conflict (though see the video to the left for some discussion of the subtleties of this point). From a lifecourse perspective, rural-urban and international migrants are also at greater risk of a range of non-communicable diseases including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and several cancers, with poor outcomes linked to impaired access to health services.

|

Further reading

A wealth of resources on climate change and environmental migration are available at the International Organization for Migration's Environmental Migration Portal and from the UK Climate Change and Migration Coalition website.

- International Organization for Migration. IOM outlook on migration, environment, and climate change. IOM 2014.

Compilation of briefings on environmental migration from the IOM. - Celia McMichael et al. 'An Ill Wind? Climate change, migration, and health'. Environmental Health Perspectives 120(5). 2012.

Recent review article from leading migration and health researchers. - Alex Randall et al. Moving stories: The voices of people who move in the context of environmental change. COIN 2014.

Bringing the voices of people who move under environmental change to the climate migration debate. - Alex Randall, 'Climate refugees? Where's the dignity in that?' Guardian. 17 May 2013.

Coordinator of the Climate Change and Migration Coalition explores definitional issues and political problems with the climate-migration narrative - Ilan Kelman, 'Difficult decisions: Migration from Small Island Developing States under climate change'. Earth's Future 3(4):133-42. 2015.

Disaster risk researcher explores history of and decision making around environmental migration from small island states