GREATEST OPPORTUNITY? THE HEALTH COBENEFITS OF CLIMATE ACTION

Tackling climate change could be the greatest global health opportunity of this century. Many mitigation and adaptation responses to climate change are “no-regret” options, which lead to direct reductions in the burden of ill-health, enhance community resilience, alleviate poverty, and address global inequity ... These strategies will also reduce pressures on national health budgets, delivering potentially large cost savings, and enable investments in stronger, more resilient health systems. From 'Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health', report of the second Lancet commission on climate change and health

Our unsustainable exploitation of earth's natural resources threatens to undermine the planetary systems upon which our societies and lives depend; that alone should be motivation enough to work towards a more sustainable politics and economy. But not only are these changes necessary; they are also the key to achieving better public health, independently of their effects on the climate. More efficient, equitable access to clean energy; urban environments designed for living, walking and cycling, not just for cars and freight; healthy, plant-based diets; and enhanced reproductive autonomy via access to family planning and contraceptive services - all key policies for better public health that will also reduce the damage we are doing to our environment.

|

The key message of this section is that many important climate mitigation interventions are 'no-regret' policies from the public health perspective, affording public health gains at the same time as reducing emissions. Several key reports make this case, most prominently the 2015 2nd Lancet commission on climate change and health. It builds on previous work, including series in both the BMJ and Lancet on health and the low-carbon economy, and WHO research and support. All are excellent resources to learn more on the subject.

|

Energy generation

Our current energy system is unsustainable and inequitable; the average US citizen consumes energy at over 4 times the level the planet can support, while over 1.3 billion people in the world lack access to electricity altogether. It is also overwhelmingly fossil fuel-driven, with over 80% of the world's total primary energy supply coming from coal, oil, and natural gas. But a transition to renewable energy generation and improved energy efficiency would not only cut CO2 emissions dramatically, at the same time reducing ambient air pollution massively and bringing energy access to rural communities for which fossil fuel generated supply remains inaccessible or prohibitively expensive.

|

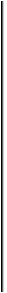

There is a close correlation between CO2 emissions and other sources of air pollution produced by different forms of energy generation (see graph). For every TWh energy generated, coal power causes a staggering 161 premature deaths; for oil, this figure is 36. By comparison, solar and wind power cause just 0.44 and 0.15 deaths per TWh (chiefly from industrial accidents). These figures do not factor in the health burdens of local environmental degradation, particularly prominent in the case of new 'unconventional' fossils. These unconventional fossil fuels - including deep water and tar sands oil, and shale gas extracted through hydraulic fracturing ('fracking') are so-called because they are inaccessible using conventional drilling or mining methods, requiring radical new methods to enable their extraction. While these technologies are too new to state unequivocally what effects they are having on the health of nearby communities, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting unique health threats related to both tar sands development and fracking.

|

In Alberta, Canada, tar sands development is contaminating the Athabasca river basin with toxic levels of waste products accumulating in animals and plants that have long formed staple foods for the Indigenous First Nations people of the region. This toxicity has been linked with elevated rates of rare cancers like cholangiocarcinoma in the area. Fracking, meanwhile, has been shown to pollute both the surrounding air and groundwater with a variety of pollutants, including some potent carcinogens. While proponents of the technology suggest this only happens in poorly-constructed wells and can be controlled with better regulation, no level of regulation has thus far proved adequate to ameliorate these threats. There is further injustice in the way both these technologies are being introduced, as poor and marginalised communities are disproportionately left to bear the health burden of industries imposed upon them. Canadian oil sands developments intrude into many First Nations territories, and the destruction they wreak destroys the boreal forest and wetlands ecosystems that such communities traditionally depended upon for their livelihoods. Fracking wells in the Eastern US Marcellus shale, meanwhile, are disproportionately positioned in the poorest neighbourhoods of the region. These inequities are, of course, further amplified by the further damage combustion of these fuels does to the climate worldwide.

A transition to renewable energy generation offers an incredible opportunity to reduce this huge environmental health burden, and at the same time establish a fairer political economy of energy. With current technologies, entirely- or majority-renewable energy generation is feasible and affordable, even in high-consumption nations like the US, or rapidly-industrialising economies like China. Less-industrialised nations, meanwhile, have the opportunity to ‘leapfrog’ these countries with renewable energy infrastructure. Renewables are better placed to bring the health benefits of energy access, particularly for the 84% of communities lacking energy living in rural areas where grid expansion is prohibitively expensive. Thus expansion of renewable energy can not only reduce the health costs of energy generation; if can also bring better health through lifting energy poverty across the world.

A transition to renewable energy generation offers an incredible opportunity to reduce this huge environmental health burden, and at the same time establish a fairer political economy of energy. With current technologies, entirely- or majority-renewable energy generation is feasible and affordable, even in high-consumption nations like the US, or rapidly-industrialising economies like China. Less-industrialised nations, meanwhile, have the opportunity to ‘leapfrog’ these countries with renewable energy infrastructure. Renewables are better placed to bring the health benefits of energy access, particularly for the 84% of communities lacking energy living in rural areas where grid expansion is prohibitively expensive. Thus expansion of renewable energy can not only reduce the health costs of energy generation; if can also bring better health through lifting energy poverty across the world.

Transport

In countries like the UK and USA, the transport sector accounts for around a quarter of all carbon emissions, approximately half of this coming from domestic motor transport (i.e. cars). Road transport in the UK also accounts for around 18% of particular air pollution, a third of NOx emissions, and the majority of carbon monoxide released. Meanwhile, worldwide physical inactivity accounts for as many as 3.2 million premature deaths annually, with the prevalence of inactivity-related disease in the UK and similar countries soaring. Try to walk or bike around London, or Los Angeles, however, and you will find it at best unpleasant, at worst impossible. This is not inevitable, or accidental, but the result of urban development that has consciously prioritised car usage over building habitable urban environments.

|

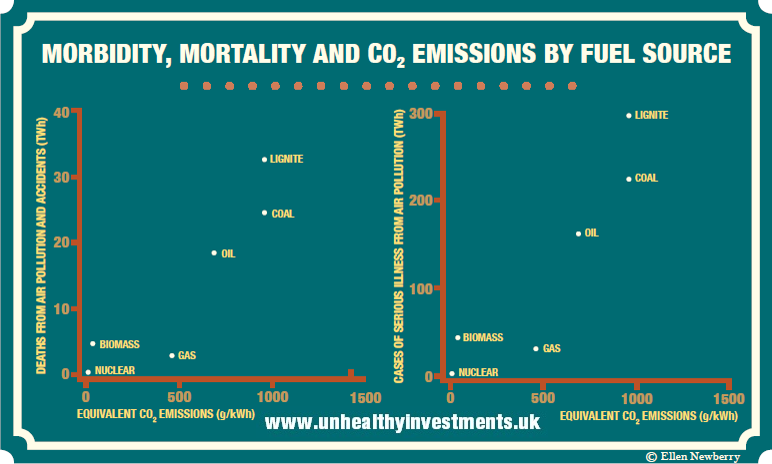

The health benefits of increased active travel are obvious. It carries the dual benefit of increased physical activity - leading to reduced risk of diseases including coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, osteoporosis, dementia, depression, and cancer - and reduced motorised transport use, cutting air pollution, road traffic injuries, noise pollution, and community degradation. A 2009 Lancet paper estimated that increased walking and cycling and reduced car use in London would prevent the loss of nearly 7500 disability-adjusted life years by 2030, including a 10-19% reduction in the burden of ischaemic heart disease. This translates to a potentially huge saving in health expenditures - one estimate calculating that, if cycling in British cities reached levels seen on the continent, the morbidity and mortality reduction would save the NHS £17bn by 2030. Contrast this with the costs of motorised transport; given the massive negative externalities related to air pollution and road traffic injuries, the cost of travel by car is massively subsidised in the UK and similar nations (see the infographic to the left, derived from Canadian data.)

|

Despite the evidence that investing in active travel more than pays for itself, support in the UK is woefully lacking. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Cycling's Get Britain Cycling report argues that local council investments of £10-£20 per head in cycling infrastructure would pay for itself (modelling studies from New Zealand suggest a payout 10-25 times that of the initial investment), yet councils in the UK outside London only spend an average of £2 per person - small wonder then that cycling modal share in British cities is dwarfed by that of other nations, with just 1-2% of journeys in London made by bike, compared to 20-40% in Amsterdam. Physical activity promotion in the UK - as with other health behaviours - overwhelmingly focuses on education and other individualistic measures, despite good evidence that this does not work; it is physical barriers like the built environment, and other social and structural influences like gender norms and a hostile conditions, that provide greater obstacles, and need changing to reap the health and environmental benefits of increased active travel.

Food

The single biggest risk factor for poor health in the UK is what we eat, accounting for over 12% of disability-adjusted life years lost to disease. And our diets are both shaped by and dependent upon fossil fuel use, and a major driver of climate change - with food production accounting for around 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions, 80% of this coming from livestock. The average UK diet produces about twice as much GHGs as a vegetarian diet, and 2.5 times more than a vegan diet, and even an omnivorous diet in line with government dietary guidelines would produce a 17% emissions reduction for the average British person.

|

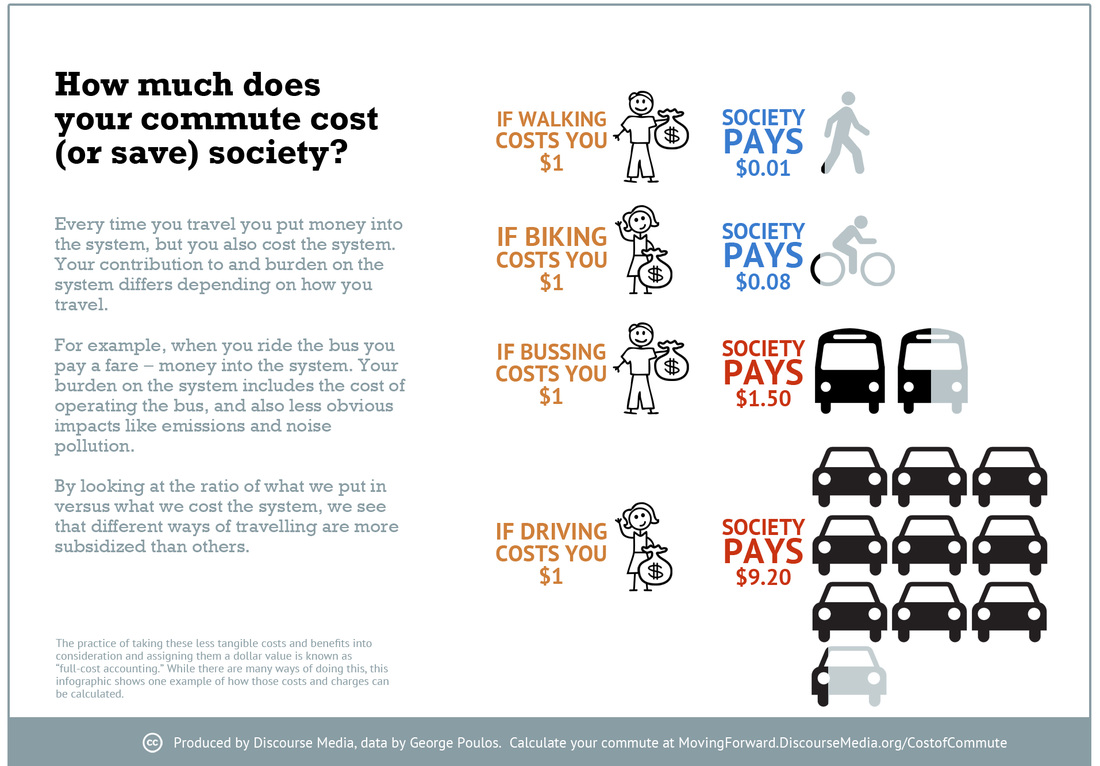

These changes would also make our diets healthier too; that 17% emissions reduction would save almost 7 million premature years of life lost across the UK over the next 30 years, increasing the average life expectancy by 8 months. And the health benefits keep growing as the emissions cuts grow deeper (see graph to right). A 30% reduction in animal products in the UK diet would cut ischaemic heart disease by 16%; more vegetarian diets would also cut diabetes, stroke, and many cancers.

But as with transport above, in the UK (and many other industrialised nations), policy approaches to dietary modification have overwhelmingly relied on individualistic, education-based approaches that we know do not work. Policy needs to act on the social and structural barriers to healthier eating, reforming the perverse incentives in the agricultural economy that reward overproduction of high-calorie, low-nutrition products, subsidise unhealthy processed foods and penalise low-carbon alternatives. A start to doing so would be to include the negative environmental externalities of food products in their prices; incorporating a carbon price into food in the UK could reduce emissions by over 18MtCO2e and avoid 7770 deaths per year. |

Fuel poverty and energy efficiency

The UK has a fuel poverty problem. The most drafty housing stock in Europe, combined with unaffordable energy prices, leaves millions of people in the UK shivering throughout the winter. Along with being linked to detrimental impacts on mental health, there is a longstanding body of evidence to show that living in a cold, damp, drafty home leads to devastating effects on physical health, such as causing and worsening cardiovascular and respiratory disease, killing thousands of pensioners and other more vulnerable people every winter. Along with reforming energy production, improved energy efficiency by properly insulating homes could cut carbon and save lives. See our guest blog from Fuel Poverty Action for more details on this topic.

Further resources

Coming soon!