Food, Climate Change and Health

These three topics are very closely related.

The food we choose to buy is probably the first or second most important decision we make in terms of our environmental impact (flying may be first but it depends on your lifestyle and diet) - and it's not all about where it's from, but also what it is. Food is certainly the biggest environmental choice most of us make regularly and can change ourselves.

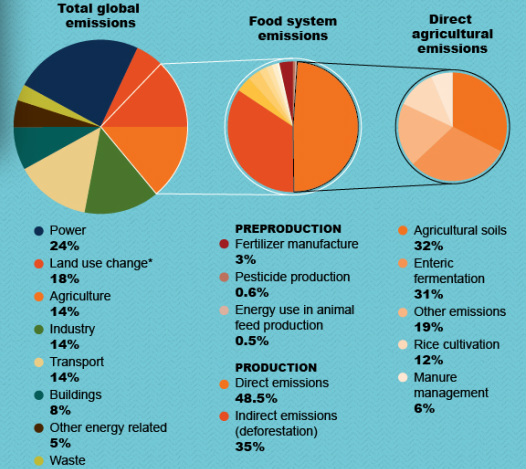

Agriculture accounts for between 17 and 32% of the world's carbon footprint directly and indirectly, and cutting back on red meat and dairy is by far the biggest thing most of us could do to reduce our 'foodprint' - the environmental impact of what we eat - and also improve our health in many cases, since most of us in the West have too much animal fat in our diets.

Meat used to be a luxury for our ancestors but now it's seen as something to eat regularly, without much thought for the health or environmental consequences of high levels of meat consumption. That doesn't mean we should all become vegetarian: better to do something than nothing. It could be a good reason to cut down a bit - especially on red/processed meat and high-fat dairy.

Why not take the part-time carnivore pledge or give Meat-free Mondays a go? We'd love to hear how you get on!

The food we choose to buy is probably the first or second most important decision we make in terms of our environmental impact (flying may be first but it depends on your lifestyle and diet) - and it's not all about where it's from, but also what it is. Food is certainly the biggest environmental choice most of us make regularly and can change ourselves.

Agriculture accounts for between 17 and 32% of the world's carbon footprint directly and indirectly, and cutting back on red meat and dairy is by far the biggest thing most of us could do to reduce our 'foodprint' - the environmental impact of what we eat - and also improve our health in many cases, since most of us in the West have too much animal fat in our diets.

Meat used to be a luxury for our ancestors but now it's seen as something to eat regularly, without much thought for the health or environmental consequences of high levels of meat consumption. That doesn't mean we should all become vegetarian: better to do something than nothing. It could be a good reason to cut down a bit - especially on red/processed meat and high-fat dairy.

Why not take the part-time carnivore pledge or give Meat-free Mondays a go? We'd love to hear how you get on!

|

|

We were one of many organisations supporting the IF campaign this year, which seeks to change 4 'big IFs' related to the fairness of the global food system; you can find out a bit more from this video or on the website www.enoughfoodif.org.

Why did we sign up? We think a fairer, more resilient food system where malnutrition is tackled now will help reduce the impacts of climate change on food security and malnutrition. Things like tax and finance are important because the impacts of climate change are mediated by social and economic systems, which are currently opaque and unfair. |

A summary of the evidence on how farming livestock, climate and health are relatedYou might have heard people discuss reducing red and processed meat consumption as a climate-health 'co-benefit' - something we could change that would benefit health and reduce emissions. You might also have heard contradictory messages - about vegetarian or vegan diets being bad for health for example, or some types of livestock farming actually helping to sequester carbon. As Healthy Planet UK, we don't take any particular stance on what anyone should or shouldn't buy and eat, in this page we're just aiming to help clarify a bit about what is known. At a global level, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization has estimated that livestock account for 18 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions-more even than all forms of fossil fuel-based transport combined - well over half emissions from all food (approx. 30%). A 2006 UN report concluded that cows might be more damaging to the climate than trucks and cars combined - especially with worldwide beef and dairy production expected to double by 2040. We hear a lot about air miles and buying local - but we rarely hear that transport accounts for only 11% of the total life-cycle emissions associated with the food we buy: shifting our diets could reduce emissions much more. |

Have a look at CGIAR's Big Facts site for some fascinating stats, facts and infographics about climate change's impacts on food production, changing patterns of consumption, undernutrition and obesity and a host of other (related) things.

The best thing about it? All the facts are based on peer-reviewed evidence compiled by scientists at CGIAR working on these topics. Amazing!! |

Other good articles and sites

- Great resources from the Harvard School of Public Health's Centre on Global Change and the Environment - http://chge.med.harvard.edu/category/healthy-and-sustainable-food

- An article that sums up the evidence - http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1839995,00.html

- For those who are more interested in the issues around agriculture and climate change and how they link to a number of important NCDs, there is an excellent document called 'Common Drivers, Common Solutions' from Iowa State University that you can download here.

- Great infographic on meat, nutrition, climate and health at http://visual.ly/meat-good-bad-complicated

Sustainable fish & seafood info:

- www.goodfishguide.co.uk (related to Hugh's Fish Fight Campaign which seeks to reduce the fact that Half of all fish caught in the north sea are thrown back overboard dead or dying).

- http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/how_we_work/conservation/marine/sustainable_fishing/sustainable_seafood/seafood_guides/ (useful if you're not UK-based as it's organised by country)

- eartheasy.com/eat_sustainable_seafoods.htm

The scientific background, for the extra keen...

In a paper published in 2008, Weber and Matthews calculate that for a US citizen, eliminating food miles entirely - almost impossible for most people - would be equivalent to driving 1000 miles fewer per year. Replacing red meat and dairy with chicken, fish, or eggs for one day per week would save the equivalent of driving 760 miles per year - and replacing them with vegetables just one day a week would be equivalent to driving 1,160 fewer miles.

Land use and land use change accounts for approx. 35% of all GHG emissions since 1850 as well as much of the biodiversity lost due to habitat destruction, and the expansion of cropland has been a major driving force in that. Meat consumption per capita is increasing around the world, especially in emerging economies, from historically low levels. Up to a point, this is a good thing for global health - increases in the amount of livestock products consumed can help to improve health, especially in countries where malnutrition, protein and mineral deficiencies affect many people.

However, well-balanced vegetarian diets can be healthy, and beyond a certain amount the benefits are negligible and excessive consumption, especially of high fat types of meat and dairy, is a contributor to obesity and many related diseases. Also important is the fact that livestock, particularly intensively reared animals, require large amounts of crops and therefore of both land and water, which are becoming increasingly scarce. The trend can push up the prices of basic food commodities, which are already increasing due to climate-related events such as droughts and wildfires, and so reduce food security in poor regions. Climate change, food security and health are closely and intricately interlinked.

This September, a study by Louise Aston and co-researchers was published in BMJ Open, which modelled the health impacts of a significant reduction in red and processed meat (RPM) consumption in the UK. They split the meat eaters into five sections based on the amount of RPM they ate, and created a hypothetical scenario in which the number of vegetarians doubled and the rest of the population all adopted the same diets as the lowest 1/5th of the meat-eaters. They found that the predicted reduction in total greenhouse gas emissions was 28 million tonnes, or 3% of the UK's total, and that the rates of coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer would decrease by between 3% and 12%.

Switching to a lower meat, lower carbon diet - like increasing levels of active travel - in the UK could also save lots of taxpayers' money, which is something we definitely need to do at present. Macro-economic analysis of a 30% decrease in saturated fat intake in the UK through reduced consumption of animal fat found that the healthcare cousts averted between now and 2030 would save approximately £5 billion in GDP: a pretty considerable sum!

Land use and land use change accounts for approx. 35% of all GHG emissions since 1850 as well as much of the biodiversity lost due to habitat destruction, and the expansion of cropland has been a major driving force in that. Meat consumption per capita is increasing around the world, especially in emerging economies, from historically low levels. Up to a point, this is a good thing for global health - increases in the amount of livestock products consumed can help to improve health, especially in countries where malnutrition, protein and mineral deficiencies affect many people.

However, well-balanced vegetarian diets can be healthy, and beyond a certain amount the benefits are negligible and excessive consumption, especially of high fat types of meat and dairy, is a contributor to obesity and many related diseases. Also important is the fact that livestock, particularly intensively reared animals, require large amounts of crops and therefore of both land and water, which are becoming increasingly scarce. The trend can push up the prices of basic food commodities, which are already increasing due to climate-related events such as droughts and wildfires, and so reduce food security in poor regions. Climate change, food security and health are closely and intricately interlinked.

This September, a study by Louise Aston and co-researchers was published in BMJ Open, which modelled the health impacts of a significant reduction in red and processed meat (RPM) consumption in the UK. They split the meat eaters into five sections based on the amount of RPM they ate, and created a hypothetical scenario in which the number of vegetarians doubled and the rest of the population all adopted the same diets as the lowest 1/5th of the meat-eaters. They found that the predicted reduction in total greenhouse gas emissions was 28 million tonnes, or 3% of the UK's total, and that the rates of coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer would decrease by between 3% and 12%.

Switching to a lower meat, lower carbon diet - like increasing levels of active travel - in the UK could also save lots of taxpayers' money, which is something we definitely need to do at present. Macro-economic analysis of a 30% decrease in saturated fat intake in the UK through reduced consumption of animal fat found that the healthcare cousts averted between now and 2030 would save approximately £5 billion in GDP: a pretty considerable sum!

The hidden costs of a Big Mac

|

Video produced by Emily Stewart, Seattle About the video: "What started as a US-based burger joint has expanded across the globe, and its varied menu now includes everything from salads to shakes to breakfast sandwiches. But the Big Mac is one beloved meal staple that has a long standing on the McDonald’s menu, no matter what country you’re dining in. If you’ve eaten a Big Mac, however, you might not be aware of everything that made that burger happen. The following video takes a look at the real cost of a Big Mac burger, from the health and environmental factors to economic contributions. One thing’s for sure—there’s more to a Big Mac than meets the eye." |