URBAN GREEN SPACE AND GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

|

One of the major demographic trends of the 21st century will be the increasing urbanisation of populations worldwide, as rapidly-industrialising nations move toward the industrial and service economies seen in high-income nations. This may in fact exacerbate many of the health risks posed by climate change, as urban environments can worsen the effects of events such as heat waves and flooding. But careful urban design - incorporating 'green infrastructure' - is not only able to mitigate some of these risks; access to green space also offers a range of health benefits, from improved physical activity to better mental wellbeing. Not to mention that there are few better carbon sequestration technologies than trees!

In this section we review the climate mitigation and adaptation possibilities of smart urban design, and introduce the health benefits of green space access. |

Key points

|

Green infrastructure for climate resilient communities

Urban environments - concrete- and population-dense, soil- and vegetation-poor, heighten risks for a range of climatic effects on health. And within towns and cities these risks are distributed unevenly, with the most climate-vulnerable regions often being where the most deprived communities live (this interactive map of climatic risks allows you to explore the spatial distribution of climate risk in the UK further). But careful use of so-called 'green infrastructure' - non-built up land featuring vegetation, trees, bodies of water (think parks, commons, public gardens) can help make communities more resilient to these threats.

|

The NHS Forest project uses NHS estates to improve access to green and wild spaces

|

One important example is the 'urban heat island' effect - the increase in average temperatures in urban areas relative to surrounding countryside due to heat absorption and storage by urban infrastructure and heat-generating urban activities (e.g. energy use). This can have a profound effect during heat waves - elevating temperatures in London by as much as 9C during the August 2003 heatwave - but expanding green infrastructure can reduce this substantively through shade, evapotranspiration, and converting radiation to latent heat. One study found that a 10% increase in tree cover in Manchester could reduce average temperatures by 2.5C in higher warming scenarios, with the cooling effect of trees being detectable as much as 80m away from small parks, and even up to 400m away from large green areas like Kensington Gardens in London. This tree cover also works to reduce air pollution, absorbing volatile organic compounds (VOC) and trapping particulate pollution - roadside trees are able to reduce indoor particulate air pollution (PM) levels by as much as 50% (though if trees are chosen inappropriately for the climate, they can also exacerbate air pollution by VOC release).

|

Areas of green space also help prevent flooding in built-up regions by allowing water to infiltrate into soil, a procedure inhibited by paved urban surfaces. Trees also slow downstream flood flow passage and reduce overall flow volume by absorbing some water. Green roofs inhibit flash flooding by slowing runoff, as do tree and grass cover. This process also improves water quality, vital for increasing demand on water services in growing urban environments; urban trees filter rainwater at the canopy and root level, removing a range of pollutants and enhancing sediment retention.

Health benefits of access to green space

In addition to the central role green infrastructure will play in helping urban communities adapt to the health risks posed by a changing climate, access to green space also provides a huge range of potential benefits for mental and physical health. Interest in research on the links between green space and health has grown since a celebrated study published in Science suggested that postoperative patients were happier, had reduced analgesic requirements, and shortover post-operative inpatient stays when their bed offered a window view of a natural landscape. Research now increasingly suggests effects of exposure to nature on depression, attention, and cognitive development in children, as well as highlighting the role of green urban environments in promoting active transport.

|

Research on this topic is complicated by difficulties in controlling for confounding economic and psychosocial variables, and the temporally-extended life-course influences of the putative mechanisms relating green spaces and health, but a body of (chiefly cross-sectional) studies provides fairly weak but remarkably consistent evidence of the positive influence of green spaces on health, supported by longitudinal cohort studies indicating reduced all-cause mortality associated with green space proximity, even after controlling for variables such as air pollution. Certainly, green space exposure makes people feel healthier and happer - the effects on perceived health of having a high density of trees in one's living environment is equivalent to moving to a neighbourhood with $10,000 per year higher median income, or being 7 years younger; and having green space nearby provides a boost to reported happiness 28% that of being married (relative to unmarried), or 21% that of being employed rather than unemployed.

One important putative mechanism linking green space to health is its effects on increased physical activity, both for leisure and transport. While the evidence on this point is not entirely unequivocal, there is consistent intermediate-grade evidence of an association between green space accessibility and increased physical activity, with the effects perhaps being more pronounced for lower socio-economic status groups and amongst demographic groups who tend to exercise less. This suggests green space is one part of creating urban environments more supportive of physical activity - see the 'transport' section of our page on mitigation cobenefits for more on that subject. |

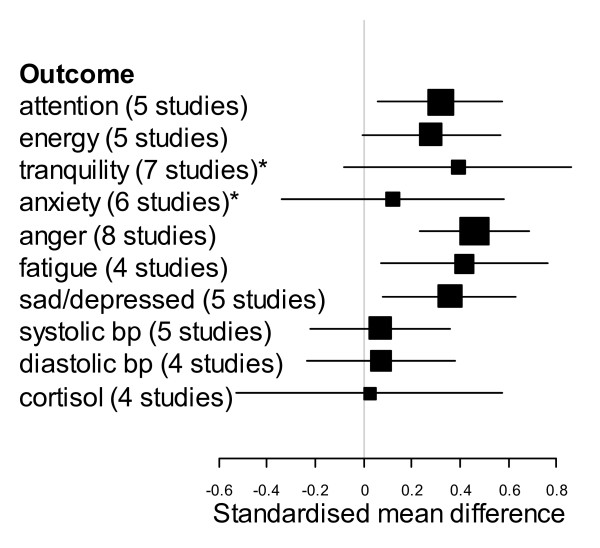

Green spaces also have a significant influence on our mental health and wellbeing. Exposure to nature for periods as short as a 15-minute stroll provide a boost to positive emotions, with more pronounced benefits - including a large increase in memory span - for more severely depressed individuals. Spending time in parks can have a powerful restorative effect, offering significant boosts to attention in both adult and child populations - the latter in particular for those with attention deficit disorder. Green space exposure appears to have an additional significance for children's mental wellbeing, given evidence of a role in promoting cognitive development - serial testing showing consistently higher working memory development for children living in greener areas than less-green ones, an effect still present even after controlling for air pollution. Other studies have also linked green space exposure to effects on stress, anxiety, fatigue, and aggression (see graph and link above).

This impressive array of health benefits has given rise to an increasing phenomenon of doctors making 'green space prescriptions' for their patients, advising them to spend time in natural environments. Such efforts, however, are likely to be of limited benefit without simultaneously paying attention to the structural barriers that prevent some patients doing so - most notably, lack of easy access to such spaces. The imperative to work for better urban design and planning with green infrastructure at its heart is underlined by the observation that exposure to the natural environment - in contrast to many health promotion interventions - offers the greatest benefits to those comparatively worse-off; thus improving green space access may be an important means of addressing health inequalities. There is already some evidence to this effect, demonstrating that in England populations exposed to greener environments have lower levels of income-related health inequality, in particular for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease.

This impressive array of health benefits has given rise to an increasing phenomenon of doctors making 'green space prescriptions' for their patients, advising them to spend time in natural environments. Such efforts, however, are likely to be of limited benefit without simultaneously paying attention to the structural barriers that prevent some patients doing so - most notably, lack of easy access to such spaces. The imperative to work for better urban design and planning with green infrastructure at its heart is underlined by the observation that exposure to the natural environment - in contrast to many health promotion interventions - offers the greatest benefits to those comparatively worse-off; thus improving green space access may be an important means of addressing health inequalities. There is already some evidence to this effect, demonstrating that in England populations exposed to greener environments have lower levels of income-related health inequality, in particular for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease.

Further resources

- The NHS Forest is a Centre for Sustainable Healthcare-coordinated project aiming to utilise the extensive estates of NHS organisations to increase public access to green and wild spaces near to their homes and to encourage health workers to enjoy themselves and to promote for their patients the health benefits of green space access.

- The Forestry Commission's Forest Research unit hosts a range of review articles covering the role of forests, green spaces and other green infrastructure in health and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

- This curated bibliography of greenspace and health research provides a regularly-updated summary of evidence on the relationship between green spaces and health.