ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE - GREATEST THREAT TO GLOBAL HEALTH?

Far-reaching changes to the structure and function of the Earth's natural systems represent a growing threat to human health. And yet, global health has mainly improved as these changes have gathered pace. What is the explanation? ... [It] is straightforward and sobering: we have been mortgaging the health of future generations to realise economic and development gains in the present. By unsustainably exploiting nature's resources, human civilisation has flourished but now risks substantial health effects from the degradation of nature's life support systems in the future.

Exploring the interaction of human activity and the environment in the Anthropocene may be of great interest to geographers and biologists, but what makes it a concern for health workers? The simple answer is that health effects from changes to the environment including climatic change, ocean acidification, land degradation, water scarcity, overexploitation of fisheries, and biodiversity loss pose serious challenges to the global health gains of the past several decades and are likely to become increasingly dominant during the second half of this century and beyond - so much so that the authors of the 2009 Lancet commission on climate change and human health described it as the "greatest threat to global health of the 21st century." Unpicking the nature and magnitude of this threat is complicated by the array of factors involved, the diverse mechanisms by which human activity, the environment, and human health interact, and the role climate change and other environmental variables play as a "threat multiplier" for other global health challenges. In these pages we'll begin to unpick some of the most important points for health workers

|

Several recent reports explore the health impacts of different dimensions of global environmental change in great detail. The 2015 Lancet commission on climate change and health explores the health impacts of climate change and fossil fuel combustion, building on the work of the previous 2009 commission. The WHO Convention on Biological Diversity published its State of Knowledge review on Biodiversity and Health around the same time. The Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on Planetary Health situates both of these in the broader context of anthropogenic influences on the environment and the social and political failures responsible for these harms.

|

The health burden of a high-carbon society

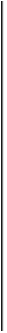

In March 2015, atmospheric CO2 concentrations broke the threshold of 400 parts per million (ppm). This came more than three decades after the internationally-recognised 'safe' threshold of 350ppm had first been broken, following an explosion in global net CO2 emissions. The mechanisms through which this expansion in fossil fuel use affects human health are diverse (summarised in the image from the 2015 Lancet commission on climate change below), but the impacts are undeniable. The WHO estimates that from 2030-2050, climate change will increase premature mortality by 250,000 deaths per year - a figure they acknowledge is likely to be an underestimate, only incorporating additional deaths from diarrhoeal disease, malaria, malnutrition and extreme weather events. More comprehensive estimates put this attributable mortality figure at 400,000 deaths per year already. And that is ignoring the other health costs of fossil fuel use, from ocean acidification and air pollution to the mental and physical health costs of extraction-induced environmental degradation.

|

To simplify this complex causal network, the IPCC divides the health impacts of climate change into three broad classes. The direct effects are those health-damaging events directly arising from a changing climate: floods, heatwaves, droughts, landscape fires, and climate-sensitive natural disasters. While these might be the most obvious consequences of climate change for health, they are not necessarily the most serious; the greater burden of disease is likely to arise from the downstream effects of climate-induced perturbations on other systems. The IPCC divides these indirect effects into two classes: those mediated by natural systems - for example, altering distributions of infectious diseases, increased food and water contamination, and changes in vector ecology spreading diseases like malaria and Dengue fever; and those mediated by human and social systems - where climatic factors exacerbate stresses on social processes already under pressure, causing forced migration, food and water insecurity, conflict, and mental stress. This is obviously a somewhat artificial distinction and the three classes are far from independent, but it provides a useful organising metaphor for breaking down the kinds of problems health workers will have to face in a clinical practice defined by a changing climate.

|

Direct effects

If the most obvious measure of a changing climate is the increase in average temperatures, then the most straightforward health impact of those changes come directly from the temperature increase. Rising temperatures affect human health both chronically - with heat-related hospital admissions predicted to more than double in 2021-50 relative to 1981-2010 due to climate change - and acutely from heat waves like that in India in the summer of 2015, which claimed over 2000 lives. Rising temperatures cause worse health through disrupting the ability of those with already-impaired temperature homeostasis (e.g. older populations, infants, and those living with some chronic diseases) to maintain a constant body temperature, and through exacerbating air pollution through landscape fires - the 2010 Russian heatwave is thought to have caused an additional 11,000 premature deaths from increased particulate air pollution as a result of the widespread forest fires in the Moscow region. With climate change, those record temperatures in Russia are predicted to become the new normal. Heat-related morbidity is likely to be increased by social factors including increasing urbanisation and land use change.

Other direct impacts include those arising from climate-sensitive natural disasters such as flooding, hurricanes, and droughts. Figures from the World Meteorological Organisation indicate a 5-fold increase in the frequency of climate-sensitive natural disasters since the 1970s. These natural disasters do not only bring the direct impacts of traumatic injuries and drowning, but also have longer-term consequences for health factors including food and water contamination, economic wellbeing, and mental health problems such as post-traumatic stress.

Other direct impacts include those arising from climate-sensitive natural disasters such as flooding, hurricanes, and droughts. Figures from the World Meteorological Organisation indicate a 5-fold increase in the frequency of climate-sensitive natural disasters since the 1970s. These natural disasters do not only bring the direct impacts of traumatic injuries and drowning, but also have longer-term consequences for health factors including food and water contamination, economic wellbeing, and mental health problems such as post-traumatic stress.

Indirect effects - natural systems

|

Humans inhabit complex ecosystems, our health interdependent with that of the animal and plant life we share our environment with; the perturbations those systems face from a changing climate will pose an additional health threat. Damage to many ecosystems is being accelerated by climate change-related processes (see 'Biodiversity' and 'Ocean acdification' below), while others are changing in harmful ways.

The geographical distribution of many infectious diseases is spreading with changing temperatures and rainfall pattern, with the malaria vector Anopheles mosquito now found at higher altitudes and in new territories, and other vector-borne diseases such as Dengue fever showing similar patterns of spread. The pathogens responsible for diarrhoeal disease are particularly sensitive to climatic factors, and the WHO predict an additional 48,000 deaths per year from diarrhoeal disease due to climate change; this will be even worse in areas hit by flooding, which contaminates clean water supplies and creates breeding grounds for lethal bacteria like cholera. |

This Lancet video summarises the direct and indirect impacts of climate change on human health

|

Climate change is also disrupting plant ecosystems vital for human life. Crop failures due to drought and temperature increase will increase undernutrition - leading to a predicted 95,000 more childhood deaths per year through the 2030-50 period - as well as desertifying previously arable land, removing some sources of food altogether. What crops are grown are also becoming less nutritious, as elevated atmospheric CO2 lowers the content of many important nutrients such as zinc in staple crops such as wheat, rice and soya. 138 million more people will be at risk of zinc deficiency by 2050 as a result of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, the majority of those in Africa and South Asia.

Indirect effects - social systems

The last group of climate health risks is harder to quantify, but potentially the most severe. Resource depletion, land loss and land use change, extreme weather events, altered working environments, and many more climate-sensitive factors besides have the capacity to disrupt the human and social systems that support today's complex, globalised societies, with a potentially catastrophic health cost.

|

As described above, climate change threatens reduced crop yields and water shortages in many regions of the globe. Stable societies with strong infrastructure, trade connections and redundant capacity are able to adapt to these shortages; but in more fragile communities - those dependent on single sources of water or food, for example, or where political or social marginalisation excludes certain groups from access to scarce resources or decision-making around their distribution - food insecurity, famine, and social unrest may result. Access to water resources (and infrastructure projects such as dams that redistribute water) have long been a source of conflict, as documented exhaustively in this interactive map; this situation will only be exacerbated by climate change.

Climate change will make conflict more likely through other mechanisms too; while climate and conflict research is notoriously controversial, and causal attribution of climate change as a role in individual wars very difficult, the largest meta-analysis of the subject provides strong evidence that climatic factors have played an important role in provoking conflict through different historical periods and across the globe. There is evidence that both the civil war in Darfur and the current Syrian crisis were made more likely by climatic impacts on land use, drought, and food security. The best way to think of the role of climate change in conflict - as in its other indirect, socially-mediated impacts - is as a 'threat multiplier', adding further stresses to already-burdened systems and identifying weak points in fragile social structures. The effect of climatic stresses on social systems will not be felt only in our physical health, but in worsening mental health as well. This may be due to acute stresses such as PTSD following conflict, extreme weather, or forced migration (while putting figures on the number of 'climate migrants' is a difficult and not necessarily helpful exercise, the UN International Organization for Migration's figure of an additional 200 million migrant journeys is a broadly accepted figure illustrative of the magnitude of the problem), but also from longer-term environmental change. |

A lot of the evidence for longer-term mental health impacts of environmental change come from research performed during the Australasian drought of the late 2000s. While not univocal, most researchers discovered that incidence of depression, anxiety and stress-related illness rose and general emotional wellbeing fell amongst affected populations, particularly in rural areas. While some of this was attributed to the importance of farming to the rural economy and consequent effects of drought on economic wellbeing, these effects were not only found amongst farming communities. For some (perhaps particularly in Indigenous communities) the disruption of the landscape that they lived in and upon as directly causing the distress. This phenomenon led one Australian psychiatrist to coin the term solastalgia - "distress that is produced by environmental change impacting on people while they are directly connected to their home environment." Such effects are produced not only by open environmental change, but also the local impacts of fossil fuel dependence - the phenomenon was first noted in response to the environmental destruction wrought by opencast mining in New South Wales.

Air pollution

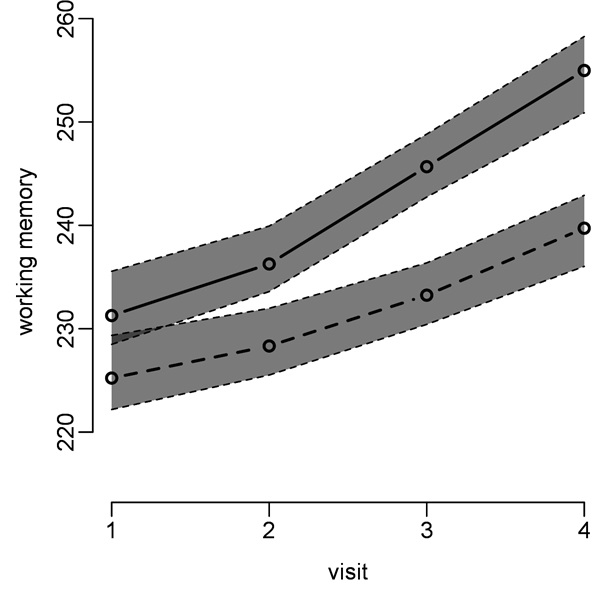

Health burden of air pollution from coal power in the EU (Source: HEAL)

Health burden of air pollution from coal power in the EU (Source: HEAL)

While climate change might be the most-publicised threat arising from a carbon-dependent society, fossil fuel combustion produces a range of other pollutants that, if anything, have an even greater health cost. Particulate air pollution caused over 7 million premature deaths in 2012 - that's 1 in every 8 deaths. That figure includes both ambient air pollution - whose major source is fossil fuel combustion, but also includes landscape fires, desert winds, and other processes - and indoor air pollution, from biomass and coal burning for heat and cooking without adequate ventilation; the morbidity and mortality split is about 50/50. While the majority of these deaths are in rapidly-industrialising nations such as China and India (according to the 2010 Global Burden of DIsease report, ambient air pollution cost Indian people 17.7 million healthy years of life), air pollution is a major health threat across the world. Ambient air pollution causes 29,000 premature deaths every year in the UK, while the Health and Environmental Alliance estimates that air pollution from coal energy generation in the EU alone causes health impacts with a total cost to EU health systems of over 42bn euros per year.

Air pollution has a wide range of impacts on health. Most prominently, it is a major cause of both cardiovascular and respiratory disease, but it has also been linked to pathologies from inflammatory bowel disease to Alzheimer's. Particulate air pollution is a recognised group 1 (highest-risk) carcinogen, greatly increasing risk of lung cancers and also contributing to bladder cancers. WHO global health observatory data breaks down air pollution-related mortality by major cause and geographical region, highlighting the impacts of ambient air pollution from stroke in adults to acute respiratory infections in young children - explore the data here.

Air pollution has a wide range of impacts on health. Most prominently, it is a major cause of both cardiovascular and respiratory disease, but it has also been linked to pathologies from inflammatory bowel disease to Alzheimer's. Particulate air pollution is a recognised group 1 (highest-risk) carcinogen, greatly increasing risk of lung cancers and also contributing to bladder cancers. WHO global health observatory data breaks down air pollution-related mortality by major cause and geographical region, highlighting the impacts of ambient air pollution from stroke in adults to acute respiratory infections in young children - explore the data here.

|

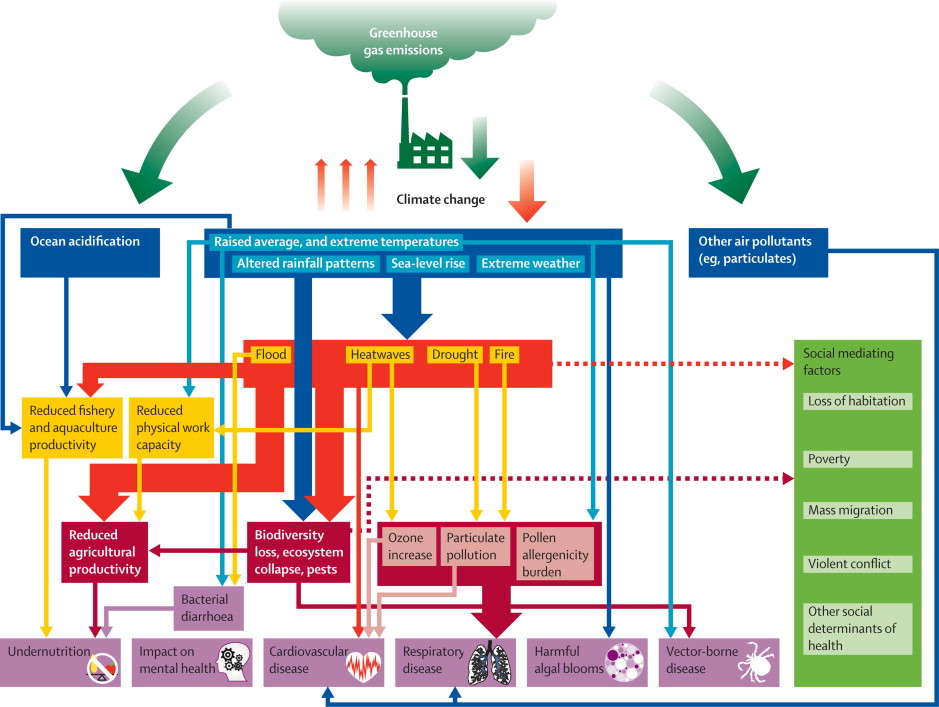

From a life-course approach, the developmental impacts of air pollution are of particular concern, with detrimental impact on respiratory and cognitive development in particular, these effects showing even in utero. In India, over 40% of children in Delhi (the city with the highest level of small particulate [PM2.5] pollution in the world, according to WHO figures) showed restricted lung function (compared to around 20% of rural controls). And even within a single city, higher air pollution exposures at school correlate with impaired development of working memory, even after controlling for social, economic, gender, age, and home exposure-related factors.

Air pollution is also an important concern from an environmental justice perspective. In the UK, while higher socio-economic status groups disproportionately produce air pollution (especially from road traffic), it is poorer communities - with low rates of energy usage and car ownership - who suffer from the greatest burden of ill health. For more on this topic, see our page on 'The environment and health equity'. While often seen to be an 'invisible killer', air pollution is increasingly becoming a focus for grassrooots environmental justice campaigning, as communities react to the health burden imposed upon them. The publication of Public Health England's air pollution mortality figures by local authority in 2014 surprised many, gaining local and national media coverage for the heavy death toll exacted by pollution. To support communities organising around these actions, see our 'Act!' pages. |

Ocean acidification

Most health students will be familiar with the carbonic anhydrase reaction - the interconversion of CO2 and water into carbonic acid (rapidly dissociating into bicarbonate and protons). It orchestrates the buffer system that serves to maintain a physiological pH within humans. The same reaction occurs in our atmosphere and oceans to maintain a chemical equilibrium. Increasing CO2 concentrations, therefore, mean increasing rates of carbonic acid formation - and ocean acidification. This may not seem to be of direct concern for humans (living on land as we do), until one remembers that many communities are partly or wholly dependent upon oceanic ecosystems for food and economic wellbeing. Much like an acidotic patient, these ecosystems are starting to collapse as they move outside their stable pH zone. Populations of certain species like molluscs and Antarctic krill are already declining, with likely knock-on effects for their many predators. These include humans, who in some areas are already feeling the costs of ocean acidification; for example, the Pacific Northwest oyster industry has been hit by this process, costing nearly $110 million and jeopardising 3200 jobs.

Biodiversity and health

|

Biodiversity - the variety of life, including species, the genes they contain, and ecosystems they form - has not traditionally been a concern for public health. But there is an increasing realisation that it underpins much of what we need for healthy lives, from clean water, to food, medicines, and infectious disease control. Biodiverse ecosystems are robust - that is, they have the adaptive capacity to remain stable in the face of external disturbances. By contrast, systems with low biodiversity are susceptible to catastrophic collapse in the face of a new pathogenic influence.

The effects of biodiversity on infectious disease offer a salutary illustration of this phenomenon. In biodiverse environments, the Lyme-disease spreading black-legged tick feeds on a variety of mammals, only a few of which are able to maintain the chain of infection; but disrupt this forest habitat, and only a few mammal species (such as mice, which are able to pass the Borrelia spirochaete onto other ticks) remain, increasing the spread of disease. |

|

And the intensively-cultured, low-variation environments of single-species factory farms provide ideal incubators for infectious diseases to spread, mutate, and reassort - the two most recent cases of antigenic shift in influenza - 'swine' and 'avian' flu - have both originated in intensively-reared animals. To combat the bacterial infections that run rampant in industrial animal farming as a result of this process, farmers turn to increasingly higher usage of prophylactic antibiotics, a major driver of antimicrobial resistance worldwide. There is epidemiological evidence, by contrast, that higher biodiversity is protective against a range of infectious diseases, with malaria and respiratory and diarrhoeal disease incidence negatively correlated with environmental protections in the Brazilian Amazon.

A cone snail. Photo: Richard Ling

A cone snail. Photo: Richard Ling

While we're not massively keen on the coldly economistic terminology, another way to understand the importance of biodiversity for human health is in terms of 'ecosystems services' - the functions diverse ecologies play in maintaining public goods vital for human societies. Forest and wetlands systems, for example, are central to the provision of clean, fresh water in many regions of the world, plant species serving to filter and purify water, while woodlands stabilise and reduce the saturation of soil on steep surfaces, preventing landslides and flooding. Plant life plays a similarly important role in regulating air pollution; not only do plants form one of the most important carbon sinks worldwide, they also reduce other gaseous (e.g. SO2) and particulate pollutants, with measurable health benefits. Biodiverse ecologies are vital for research, too. More than half of all drugs registered with the US FDA in the 1981-2010 period were derived from natural sources, the figure for new antimicrobials being even higher - as much as 80%. But human activity is threatening these natural reservoirs of pharmaceutical innovation. Deforestation in the Amazon threatens the extinction of the tree frog species whose toxins underpin our understanding of local anaesthetic and muscular relaxant agents still in use today. And climate change and ocean acidification are destroying barrier reefs, and with them the cone snail species (pictured) whose potent toxin is being used to develop new painkillers, while destroying the Arctic habitat of polar bears will deny us the chance of understanding how they manage to avoid renal failure, diabetes and osteoporosis in circumstances that would cause these conditions in other mammals like us.

Health benefits of a changing climate?

Some commentators suggest that, while climate change is happening and due to human causes, we need not worry too much about it because it will in fact have many beneficial impacts. Some of those suggested relate to health; fewer cold-related deaths and higher crop yields in temperate zones are the ones most frequently cited. Without going into this topic in too much detail, it is important to acknowledge that some regions, in certain specific ways, may see some health benefits from the changes our climate is facing. However, these are likely to be smaller in magnitude than often suggested, and certainly will be far outweighed by potential damages - either to different aspects of health, or in different geographical regions. On crop yields, best simulation evidence suggests that, while there may be a short-term boost to yields in some temperate zones in the earlier part of the 21st century, this will be more than cancelled out by reductions elsewhere, and even temperate zone yields will drop in the later 21st century without significant mitigation and adaptation. As for cold weather, the bulk of winter deaths in temperate zones - due to cardiovascular disease - show little to no temperature correlation, while overall mortality does not appear to reduce significantly with temperature increase. This paradoxical conclusion may be because winter mortality is more closely related to indoor living temperature than conditions outside - and thus interventions to improve energy efficiency and fuel poverty (see our page on the health cobenefits of mitigation) are better strategies for health promotion that waiting for the world to warm!

Issues in global health and the environment

As we argue above, environmental health is an important factor in almost all global health issues facing the world today. Are you interested in a particular health and development topic, and want to know more about how global environmental change is affecting it, and the cobenefits of environmental protection? You'll find more information on our special topic pages, covering:

- Food and agriculture

- Environmental health and health equity

- Water

- Gender and women's health

- Child health

- Migration

- Conflict

- Mental health

- Energy policy and development