CREATING A LIVABLE ANTHROPOCENE: THE ROLE OF HEALTH WORKERS

|

So, humans are changing the natural environment in radical and unpredictable ways; global environmental change poses an immense threat to global health; but acting to protect the environment and mitigate climate change could be the greatest public health opportunity of the 21st century. Even if that is all the case, why should it be important for health workers? And how can they act on this knowledge? We contend that the health sector has a vital role to play in the transition to a more sustainable society, both in advocating for the political and social conditions that make the transition possible, and in making health and health care itself more sustainable.

In this section we review the environmental impacts of healthcare in the UK and worldwide, identify some practices that make it unsustainable and highlight programmes seeking to cut emissions and improve patient care. We also highlight the important political role health workers and their organisations can play in bringing the health frame to national and international climate policy negotiations; health workers are the most trusted professionals, and health impacts provide a concrete motivation for combatting abstract threats like climate change. |

Key points

|

Healthcare without harm - creating sustainable health systems

In industrialised nations like the UK, a highly-intensive model of interventionalist, curative medicine is practiced - often to cure the late-stage manifestations of diseases that are produced by those same resource-intensive ways of living. The economic cost of such medical practice is deemed newsworthy on a regular basis (usually in a bid to push punitive policies limiting health and social care support for the most marginalised in our societies); however, the environmental cost of this approach to health care is less regularly discussed.

|

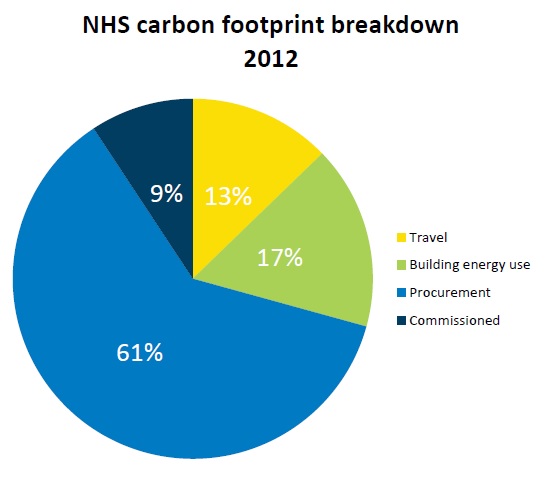

Latest estimates of the 2012 carbon footprint of the health care sector in England (including the NHS, public health, and social care) comes to 32MtCO2e – 40% of public sector emissions – out of a total UK footprint that year of 571.6MtCO2e (NB this includes Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, whose contributions are not included in the health care sector footprint). Previous estimates of the US health sector’s footprint have claimed that it accounts for 8% of the nation’s total GHG emissions. But a carbon-dependent health system is not inevitable. The Cuban health care system uses just a tiny fraction of the resources of the US or UK health systems (spending just $430 per capita on healthcare – contrast this to the UK and US figures of $3,322 [still one of the most efficient in OECD nations] and $8,608 respectively), yet still achieves comparable or even better outcomes on many metrics of population health. The so-called ‘Cuban paradox’ shows that it is entirely possible to achieve more sustainable models of healthcare and limit the extent to which it exacerbates global environmental health threats.

As shown in the image to the left, the ecological footprint of UK healthcare is rather heavily due to the goods we consume - 'procurement' (the general term for goods and services consumed by the health sytem) makes up over 60% of the carbon footprint. Breaking this category down shows major offenders to include pharmaceuticals (21% of the overall footprint) and medical instruments (11%). |

The carbon hotspots in the NHS footprint highlight how models of care need to change to produce health systems fit for the future. Part of the answer lies beyond the health system - moving away from individualistic health promotion strategies based on exhorting people to eat less and move more, and instead building environments that support healthy communities. As David Pencheon, director of the NHS Sustainable Development Unit, argues, we need a true National Health Service - one in which unplanned hospital admissions are deemed a sign of failure until proven otherwise. But there are also more direct actions health systems can take. Change how care is funded, so - unlike with the present NHS tariff system - activity is not rewarded for activity's sake (making an ounce of cure worth a pound of prevention rather than vice versa). Use education and technology to empower patients to manage their own care, Use more rational prescribing to cut the vast carbon cost of pharmaceuticals, while simultaneously making healthcare more effective and economical. And so on.

|

Slides adapted from a Healthy Planet workshop run by Shuo Zhang at the Medsin conference, Warwick 2012

|

The good news is that health care systems are beginning to wake up to the 'win-win-win' scenario of more sustainable health systems that are cheaper, provide better care, and are better for the environment. In the UK, the NHS Sustainable Development Unit works to monitor the environmental impacts of UK healthcare and to develop more sustainable policies for healthcare provision and clinical practice. The Oxford-based health workers' organisation the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, meanwhile, supports health workers of all disciplines to perform their work more effectively and sustainably, pioneering initiatives such as greener dialysis and sustainable mental healthcare, as well as making NHS facilities foci of healthier communities through initiatives like the NHS Forest. Worldwide, the Global Green and Healthy Hospitals Initiative established by NGO Healthcare without Harm connects hospitals internationally to share best practice on sustainable healthcare and improving environmental health, while the Institute for Healthcare Improvement increasingly acknowledges environmental sustainability as a core component of healthcare quality improvement.

|

Healthcare as mitigation

|

Beyond reducing the climatic harms of healthcare, some forms of health care provision can actually act as part of effective mitigation policy. As already covered, health promotion surrounding food and physical activity are obvious examples here. Another is that of reproductive healthcare and family planning. While it is important to stress, contra certain neo-Malthusian voices, that the climate crisis is not one of overpopulation – as a recent Lancet review puts it, “consumers, rather than people, cause climate change” – it is nonetheless the case that population growth (not just in terms of numbers, but in the fashion in which it grows, e.g. with increasing urbanisation and changing patterns of food and water consumption) significantly affects human impacts on the environment. Recent evidence suggests that globally there is a huge unmet demand for family planning – with as many as 200 million wanting, but lacking access to, contraceptives – and that improving access to and quality of family planning services that focus on women’s empowerment and improved reproductive autonomy can have major maternal and child health benefits, as well as contributing significantly to climate change mitigation. Improved access to such services in less-industrialised countries could reduce GHG emissions by 40% (relative to higher population-growth paths) by 2100.

Read more on this subject at our page on gender, family planning, and climate change. Health workers as advocates

A neglected but vital role that health workers have to play in the creation of more sustainable societies is that of public advocates for the health imperative for such a transition. Health workers are the most trusted professionals in society and, when they speak out, have an influential voice in policy debates. Global environmental change can seem an abstract and intangible threat, perhaps accounting for the cognitive dissonance that allows people to accept the dangers it poses while simultaneously doing little to mitigate it; framing its discussion in terms of the concrete and immediate impacts on local and global health is a powerful means of rendering it more concrete and so stimulating social and political action.

|

This is why much of Healthy Planet's work involves advocacy and activism - whether in calling for stronger action on climate change from national or international governments, or pushing for the health sector to divest from the fossil fuel industry - and so break its stranglehold on climate science and policy. See our Advocacy and Action pages for more.

Further reading

- Frances Mortimer, 'The sustainable physician'. Clinical Medicine 10(2):110-11. 2010.

- David Pencheon, 'Making healthcare more sustainable: the case of the English NHS'. Public Health. 2015.

- Muir Gray, 'An Introduction to Sustainable Healthcare'. Online learning from www.healthknowledge.org.uk

- Eric Chivian, 'Why doctors and their organizations must tackle climate change: An essay'. BMJ 348:g2407. 2014.