The plenary room in Bonn (from UNclimatechange on Flickr) The plenary room in Bonn (from UNclimatechange on Flickr) Gabriele Messori The United Nations’ climate negotiations usually gain the press spotlight once a year, when the big Conference of the Parties (COP) meeting takes place. However, the process of designing a global climate agreement is ongoing, and additional meetings are scheduled throughout the year. One such meeting is currently taking place in Bonn. The meeting addresses a broad range of topics, among which mitigation, adaptation, climate equity and climate finance. All of these are crucial for minimizing the social and economic impacts of climate change, and all can reduce the severe health footprint that a changing climate inevitably has. There is a wide consensus that time is running out and the meeting’s co-chair, Mr. Runge-Metzger, warned that if no decisive action is taken we could be looking at a 4 ˚C warming by the end of the century. This would spell catastrophe for the most vulnerable countries, such as small island states and least developed countries, Because of this, the least developed and developing countries are demanding that the developed countries step forward and take the lead, both in terms of national plans to reduce emissions and in providing climate finance. As eloquently stated by the Philippines, “In our delegation we do not speak of support... finance is a commitment by developed countries, not support.” In line with the feeling that the time is ripe for decisive action, it was decided to establish a formal negotiation group, called “contact group” in UN jargon, to continue the work on a global climate treaty. This decision will come into effect in June, when the parties will meet again to proceed with the negotiations. This is a distinct step forwards from the informal consultations that have taken place for the last two years. Besides this, however, the meeting in Bonn has had few concrete outcomes. The talks have been plagued by clashes over procedural and organizational issues, which have often overshadowed the central point of the negotiations, namely climate change. With time running out and the aim to have an ambitious global climate treaty in place by 2015, every second of negotiating time is precious. Today is the final day of meetings here in Bonn, and we all hope it will end on a positive note, preparing the ground for the next round of talks in June.

0 Comments

Alistair Wardrope The climate crisis is, first and foremost, a crisis of over-consumption. This was one of the overriding themes of the ‘Global Health and Justice in a Changing Environment’ conference this weekend. This conference, organised by the UCL branch of Healthy Planet UK, looked at the intersection of environmental change, health and social justice. The speakers highlighted how intensifying patterns of unsustainable, resource-intensive and inequitable consumption are driving global environmental change. They also demonstrated that although the crisis is primarily about consumption does not, despite what some dominant paradigms would leave us to believe, mean the solutions are all in the hands of individual consumers. Consumption is a function of interwoven social, political and economic norms, and the conference showed that the transition to a more sustainable society demands collective action to restructure those norms. This observation should be familiar to anyone who has looked at the evidence on behaviour change in health promotion. In many nations in the global ‘North’, individualism dominates in health promotion - yet individualistic interventions have largely been unsuccessful. As Daniel Goldberg has highlighted, their benefits are frequently modest and short-lived, they exacerbate already-severe health inequalities, and – through ignoring the societal factors that influence patterns of disease - can increase stigmatisation of already-marginalised groups. This individualistic approach is neatly satirised in the Townsend Centre’s alternative to the UK Chief Medical Officer’s ‘Ten Tips for Better Health’:

The Townsend Centre’s Alternative Tips highlight the absurdity of prescriptions for individual behaviour change that ignore the social context. It is the social context which shapes people’s capacity to act upon such advice, and such prescriptions also ignore the direct influence that the social environment has on health. Yet our governments have embraced a similarly individualistic approach in looking at the changes required to combat climate change. DEFRA’s Pro-Environmental Behaviours Framework, for example, provides a set of 12 “headline behaviour goals”. Following the Townsend Centre’s example, the contributions of those present at the Healthy Planet conference this weekend provide us with ample information to revise this framework in a way that better understands the social context. Pro-environmental behaviours: an alternative framework DEFRA’s first behaviour goal looks at proper water resource stewardship, but a rather different dimension of water management was, unsurprisingly, more on the minds of those present at the conference – flooding. Andrew Watkinson and Mark Maslin highlighted how flooding embodies a recurrent pattern in the consequences of climate change – those least responsible are often those worst affected.

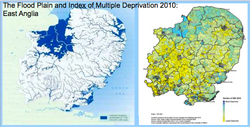

This applies not only internationally – 25% of Bangladesh being under threat from sea level rise, for example – but also within the UK; as Andrew Watkinson showed in a highly visual way (see images, left), the regions of East Anglia most threatened by flooding coincide neatly with those with the highest indices of multiple deprivation. While the distribution of these risks is to some extent about physical geography, our response to them is a matter of political will – and, as Watkinson further observed, the need for government intervention to compensate for flood damage and mitigate further flooding risks only started to move up the agenda when wealthy Thames Valley land and capital was threatened; similar discourse was notable only by its absence when flooding hit Hull and Sheffield. This is a profound injustice which we must not overlook. As Mala Rao and Ilan Kelman highlighted, there are many more dimensions than poverty alone when considering the social justice implications of climate-driven natural disasters, looking at the impact of gender on morbidity and mortality in flooding (where, for example, women and children are up to 14 times more likely to die than men, worldwide – although in some developed countries this pattern may be reversed, again due to gender stereotypes and different cultural expectations). Whose mobility, how?

Rachel Aldred left the conference in no doubt that transport was an issue of social justice. If one image alone could provide sufficient argument for that point, her photo of a Ryanair advert over a dangerous, unpleasant inner city highway (right) was it: a city designed for able-bodied, affluent car users, providing an alienating, intolerable lifestyle escapable only by cheap flights to sunnier shores. She also examined the relationship between gender and active travel in the UK, noting that our cities, where they cater to the preferences of cyclists at all, favour men’s perspectives on what makes cities fit for cycling. The ugly situation described by Dr. Aldred is in stark contrast to the potential benefits to be realised from embracing approaches to active travel that look first at the environment we create for it – Freiburg is a prominent example of what can be achieved when we look beyond the individual in trying to reduce our dependence on cars, instead creating cities that do not lead to such dependence. Energy & fuel poverty DEFRA’s goals do consider the importance of approaching energy production and consumption for tackling climate change, but entirely neglect the obstacles to this posed by a broken energy policy.

Bryn Kewley of the Energy Bill Revolution spoke of the absurdity of expecting individuals to invest in the long-term returns of better home insulation when rising UK fuel poverty means fewer and fewer are able to afford to heat their homes at all. He also offered a simple and appealing solution: invest revenue from the carbon tax in social housing stock to provide people living in fuel poverty with better insulation, at a single stroke reducing cold-related deaths, energy bills and energy consumption. Others looked at different aspects of energy policy, seeking alternatives to a UK market in which over two decades of liberalisation and a lack of concern about externalities have been dominant themes. This has resulted in investment in renewable energy R&D having collapsed, the energy production oligopoly being dominated by those companies who profited from the initial privatisation fire-sale, and most if not all major investors plough their resources into the fossil fuel industry, inflating a carbon bubble whose value is reliant upon resources we know we cannot afford to use. Partial solutions to this situation discussed at the conference included divestment from fossil fuels (as represented by a workshop delivered by UCL’s Fossil Free Campaign, part of a growing international movement for university divestment from the fossil fuel industry) and lessons from Germany and Denmark about intelligent market regulation to support community renewable energy. “The only truly progressive thing Coca-Cola could do is to go out of business.” So said Tim Lang, warning the conference how public health dimensions of food policy had transitioned in his lifetime from questions of how to produce sufficient food to prevent malnutrition, to how to control its rampant overproduction. He described a supply-driven food market that produces a situation in which it would take 4 planets for all of us to eat like an American (and 2-3 of them to support the EU); and a system of international trade liberalisation policies that spread this market globally, crippling local systems of more sustainable agriculture and diet in the process.

Buy right, recycle the packaging, and you’ve 'done your bit’. The last objectives on DEFRA’s list come to the crux of the problem: a focus on behaviour change views individuals primarily as consumers, rather than citizens, and the answer to all ills as being to provide more information and then to enable the unrestricted exercise of consumer choice. This approach breeds complacency, a theme touched upon by both Andrew Watkinson and David Pencheon, whether in the 65% of the UK public who feel they are doing their bit for the environment, by recycling and buying energy efficient fridges, or in the doctors “too busy saving patients to save the planet”.

It also neglects the many societal issues already discussed. Furthermore, this individualisation of responsibility carries much the same risks here as it does in health promotion – ineffectiveness, rising inequality, and stigmatisation.

David McCoy, the current chair of Medact, provided a striking illustration of these risks – showing us why an agenda for ‘sustainable development’ based on the neoliberal argument that 'a rising tide lifts all ships' would see the eradication of extreme poverty only in another 100 years. Moreover, tackling poverty through attempts to promote continued economic growth across the board, as opposed to a greater focus on wealth redistribution, requires a 97.5% reduction in the current carbon intensity of production to stand any chance of keeping to the 2C warming threshold. Even then, this would be at the cost of vastly increased inequality (with immense resultant damage to health and wellbeing, and to societal cohesion). It is clear that we need to seek another approach. The 2014 Healthy Planet conference did not present such an approach in its entirety, but presented some steps that could be taken towards it. The rest of the story is up to us. Contact: [email protected] Alistair is a current medical student at the University of Sheffield, unable to sever ties with former life in physics and philosophy, writing his blog, Unprincipled: bioethics against individualism, which is chiefly on health care ethics with a consequentialist/communitarian/feminist-allied flavour; occasional musings on related issues in philosophy of medicine. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed