|

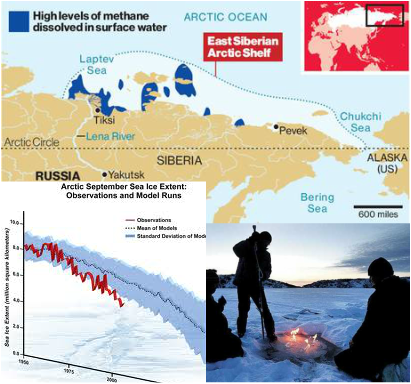

18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.

0 Comments

Bangkok floods (Source: UN/Mark Garten) Bangkok floods (Source: UN/Mark Garten) Shuo Zhang Originally published at http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/climate-change-threatens-health-in-the-new-megacities/ Weather was big news in 2012. Australia’s decade-long drought the ‘Big Dry’ ended in May, and the US drought last summer caused a major crop failure. Hurricane Sandy broke records and may well have contributed to a shift in opinion on climate change and possibly helped to swing the election in America. Then Christmas 2012 in the UK was filled with reports of severe flooding, travel delays and damage to property, coming at the end of a year that is the second wettest on record. News stories tend to focus on personal stories, injuries, economic costs and daily inconveniences, but rarely touch upon the impact of these events more broadly on urban systems, and the wider actions that governments need to take to mediate risk and manage impacts on vulnerable populations. In cities in developed countries like the UK, there are contingency plans and reasonable infrastructure for extreme events, but this isn’t the case for all cities. Beyond thinking about discrete climate events, in the developing world, the sheer rate of urbanisation means that poor neighbourhoods in many cities have sprawled onto floodplains and unstable hillsides, which is combined with insufficient infrastructure and services to support health and wellbeing. In many cases, rapid urbanisation has also been both bad for the environment, and for people. Inequality is exacerbated by the unmet demand for housing, services, transport and work. Cities themselves can contribute to ill health and obesity through poor urban planning, inadequate transport provision, pollution and unsafe roads. A lack of or poor regeneration and planning often results in damage to our mental and physical health. The concept of interlinkages between cities, health and climate change has only fairly recently started to come to the fore. When the 2008 UCL/Lancet Commission on the effects of climate change on health was first published, attention was focused on the big uncertainties and risks to health: changing patterns of infectious disease, and indirect impacts of famine, political instability and migration. Although excess deaths due to heatwaves were identified, there was little discussion of the particular vulnerabilities of people in informal settlements. Since then, droughts, storms and floods have also shown the potential for climate change to take us by surprise, and that greater effort and funding for mitigation and adaptation are needed now. Megacities at risk There is increasing urgency to focus our attentions on cities, and it is predicted that the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people living in cities will be affected by climate change over the next 5-10 years. The humanitarian imperative isn’t the only one: we must also remember that the most vulnerable have in general contributed least to atmospheric greenhouse gases. According to a UNFPA report, half of Africa’s 37 ‘million cities’ are at risk from sea-level rise and storm surges. Many Asian cities are in the floodplains of major rivers such as the Ganges, Mekong and the Yangtze. Climate change will have complex impacts on cities, and is exposing vulnerabilities in the social, economic and political fabric of our communities. The longer we wait, the more it will cost – not just in GDP as outlined by the Stern Review but in health, and in lives. We can’t just go on with business as usual. It’s not all bad news – urban environments can also allow new forms of social organisation to lead the way and offer new solutions. Cities can offer a possibility for decoupling high standards of living from high carbon footprints, and a small effort may lead to big change because of their centralised nature – for example in improving roads for pedestrians and cyclists to use. There is a range of ways to change policy and in turn change physical realities. Karachi’s Urban Resource Centre – an organisation founded by teachers, professionals, students, activists and community groups from low-income settlements – has successfully challenged government plans, showing that community action can make a difference to those living closest to the edge. For the first time in history, half the world now lives in cities, and this number is set to continue growing. We need a concerted effort to improve our global cities by putting systems in place to facilitate environmentally sustainable and healthy lives and ensuring that they are adapted to climate risk and able to protect the most vulnerable.  Land degradation (source: UN/John Isaac) Land degradation (source: UN/John Isaac) Dalvir Kular With conservative estimates forecasting a population of around 9 billion people by 2050, the question of whether the world food system’s production capacity can keep up with increasing demand is a very important one. How it can do so in a world increasingly influenced by climate change is an even tougher question. Imagine if 2013 were the year where we started to take real action on climate change. The year where we changed our course to end malnutrition, for good. I choose to be optimistic. In the global north we have warped our basic need for food into a multi-billion pound industry in which it’s not so much about nutrition but luxury…at least as long as you have the money. In the global south, the losers of our success are driven further into poverty, due to injustices in the political decisions of the global north. The lack of regulation, commodity speculation, inequitable trade policies and climate change combined are helping to send food prices through the roof for the poor. The recent launch of the ‘Enough Food For Everyone IF‘ campaign hammered home the truth that for now, there is enough food available to feed everyone on Earth, but the real problem is how to ensure that people have sufficient access to ensure their food security. Unsustainable energy use and agriculture are fueling a warmer climate, which is resulting in unpredictable and increasingly frequent natural disasters such as floods and droughts. The problems described above – and the increasing shadow of climate change – are directly and indirectly impacting on access to food for the world’s poor; and climate science tells us there’s more to come. Safety nets and speculation According to the United Nations global food reserves are at their lowest levels in nearly 40 years, meaning that there’s a much smaller margin for those already food insecure. If the cost of staples goes up 170%, people either increase their expenditure for the same amount of food, you change your diet to a cheaper and often less nutritious one or you eat less. If you’re poor, ie. when the food required to be secure represents a reasonable proportion of your income, the first option may not be open to you, and there is much less scope to adapt. Rapid urbanisation in the developing world creates the opportunity of greater inequality of livelihoods and income in a higher population density. This give rise to possible future food security issues and a need for safety nets to help city dwellers cope when food prices may be volatile in the future. Helping farmers to adapt to the impacts of climate change can defend food supplies. Laws to prevent speculation have been largely opposed by the big players. Barclays is the biggest UK operator in food commodity markets, making up to an estimated £500m from speculating on food prices in 2010 and 2011. Legislation to limit commodity speculation was backed by the EU in early 2013. Germany’s fourth largest bank, DZ Bank, has announced it would no longer speculate on food prices. Agriculture – especially large-scale, intensive farming of livestock – contributes heavily to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which in turn are a big part of the reason why we’ve been seeing crop failures all around the world, from Africa to the USA to Russia. Agriculture needs to be part of the solution – and with an increase in investment and better policies, sustainable agriculture technologies and practices may be adopted to improve food security and sovereignty for farmers and consumers in the global South, and to reduce emissions and preserve biodiversity. The recent extremely successful UK-based Fish Fight campaign, spearheaded by the food writer Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, is proof that people power – assisted by the internet and social media – can bring real change. It coordinated its supporters to send emails to MEPs in all the official languages of the EU, with more than 120,000 sent within 24 hours in a, successful, effort to ban fish discards. We need similar political momentum to set a more ambitious 40% emissions reduction target for Europe. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which receives nearly 40% of the EU budget must be reformed along the lines advocated by the ‘Enough food for everyone IF’ campaign. It suggests stopping food from becoming fuel for cars, a false economy when it comes to tackling climate change. Certainly we in Europe should pressure our MEPs to lobby for sustainable agriculture in the context of the CAP reform being carried out this year. The idea of a low GHG diet – more domestic, home grown foods, seasonal, local, and including less red meat and dairy – is far from new, but it’s one of the ways that people can make the biggest difference to their carbon footprint. The really good news is that it isn’t only more sustainable, but also often healthier too. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed