|

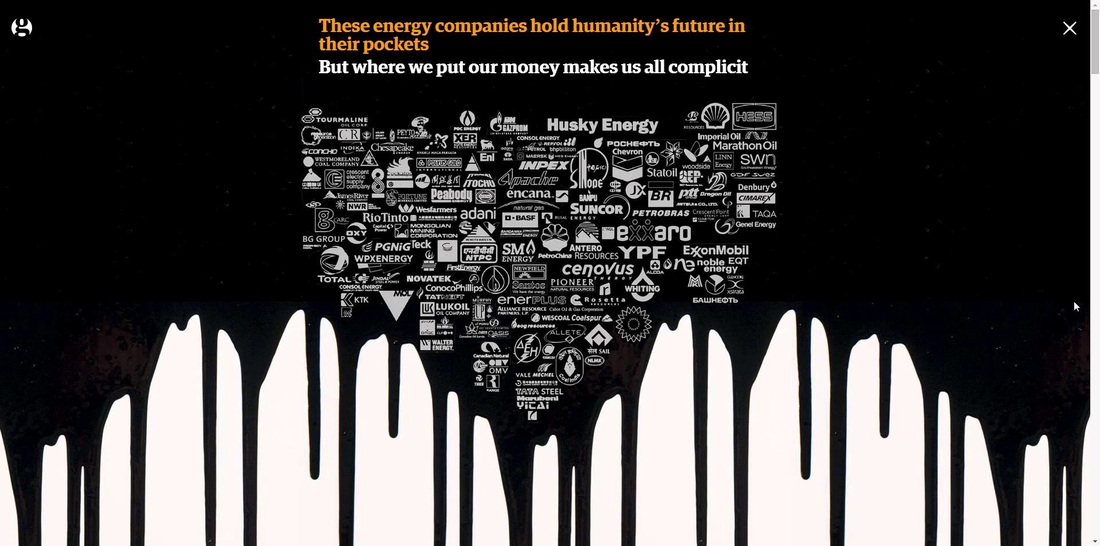

You may have noticed a running theme in the posts on the HPblog recently; we’ve been working a lot on divestment – convincing the health sector to stop funding the companies driving climate change, and instead to take its commitment to ‘do no harm’ seriously and move its money towards those working to achieve the energy transition our planet and our health requires. Health sector divestment has taken a huge step forward in the past month, since the Guardian newspaper launched its ‘Keep it in the Ground’ campaign, calling for divestment from the fossil fuel industry. What’s particularly notable about the campaign is their chosen targets – the two biggest private global health funding organisations in the world, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. It’s hard for anyone with more than a passing interest in global health to criticise the Wellcome Trust; Wellcome-funded research has achieved extraordinary advances in healthcare. They are more willing than others to fund research involving higher levels of risk, complexity and uncertainty, an approach typified by their making exploration of the connections between environment, nutrition and health one of their five ‘key challenges’. Moreover, their commitment to transparency – whether in championing open access to scientific research or in making the details of their investments freely available to the public – pervades all the Trust’s actions. But there would be little virtue in such openness if none were willing to challenge them when mistaken. Their stance on continued investment in the fossil fuel industry – as outlined in a recent Guardian article by Director Jeremy Farrar – demands such a challenge. We agree with much of what Farrar has to say. That climate change, as one of the greatest threats to global health of the 21st century, demands concerted action from health organisations. That this requires a commitment to a rapid decarbonisation of the global economy in order to remain within a 2C warming carbon budget. And that consideration of the impacts on human health and wellbeing need to be at the forefront in planning a just and sustainable transition. However, where we disagree is in the role of fossil fuels – and the fossil fuel industry – in making that transition.

He also proposes that it is from within the fossil fuel industry that the necessary decarbonisation will come, and the best way to achieve that is from within, as an active and engaged shareholder. But it is difficult to see how shareholder engagement alone could bring about the scale of transition needed with the required urgency (the IPCC’s 2C carbon budget will be exhausted by 2036 at current rates). Health institutions, more than any other organisations, should be aware that businesses stop responding to shareholder engagement when that engagement challenges the very core of their business model – it’s why it failed with the tobacco industry, and why it’s failing now with fossil fuels. Farrar is optimistic about the role of fossil fuels in a low-carbon economy – citing natural gas and carbon capture and storage as central components – but it is hard to reconcile this position with evidence that half of already-known gas reserves will have to remain unburned to stay under 2C, and that CCS will do nothing to alleviate the health burden of particulate air pollution.

Nonetheless, selective engagement may have its place alongside divestment. But it is only possible with companies who display a realistic commitment to keeping warming under 2C – one that moves beyond words. We applaud the Trust’s acknowledgement of the inconsistency of coal and tar sands development with a healthy climate. But so too is pursuing Arctic drilling, not to mention funding attempts to undermine climate science or legislative efforts on mitigation policy – of which companies in which the Trust invests are guilty. For companies that fall short of the required action, divestment must follow. While we focus here on the Wellcome Trust, that is only because their commitment to public debate permits us to engage in this conversation. The same arguments apply to all health sector organisations, who share the same responsibilities for health of people and planet alike. If, like us, you're convinced that it's time for health organisations to ditch their dirty investments, here are a few things you can do:

0 Comments

Yesterday evening marked the launch of Unhealthy Investments, the report on climate change, global health and the fossil fuel industry. Medact and Healthy Planet produced this report, published alongside the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, the Climate and Health Council, and medsin, as a tool to help health workers make the case for their representative bodies, funders, and other health sector institutions to divest from the fossil fuel industry. The report argues that:

There has been significant coverage of the report’s launch in various venues.

What now? This is only the beginning; the report and related resources, and the coverage and debate surrounding it, provide the perfect tools for healthcare students and health workers to take the case for divestment – and action on the health impacts of climate change – to their universities, trusts, unions, professional organisations, representative bodies, and other representatives of the health community. How can we go about doing this? Some ideas:

For more on divestment and health, visit the Unhealthy Investments report site: www.unhealthyinvestments.uk.

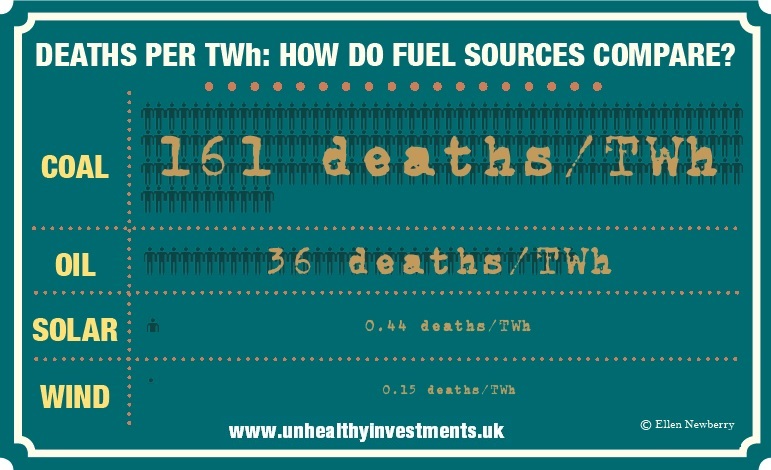

Gabriele Messori and Izzy Braithwaite Adapted from a blog post at http://climatesnack.com/2014/01/30/cough-for-coal-at-cop19/#more-1673  Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Neither of us had imagined we’d end up carrying a pair of giant pink lungs in front of the Polish Ministry of Economy on a cold November morning. Why were we there? It’s a long story… We were in Warsaw for COP19, the annual UN climate talks (COP = Conference of the Parties). The aim of the talks is to reach a global deal to tackle climate change in 2015, which will come into force in 2020. We went as part of a delegation of students from Healthy Planet UK, a small, student-led group which seeks to raise awareness about the links between climate and health, and to advocate for UK policy that benefits both health and the environment. As students, researchers and young people, our motivation was the growing body of evidence that climate change poses a major threat to global health, and that sustainable development presents major opportunities for public health. Examples of such climate-health synergies (sometimes called health ‘co-benefits’) can be found across energy, transport, housing and food policy – and quite possibly elsewhere too. Air pollution – bad for health, bad for the climate We know that greenhouse gas emissions affect health indirectly through their contribution to climate change, via changing temperatures and rainfall patterns. Although carbon dioxide has no direct health effect except at high concentrations, it is often, if not invariably, produced alongside other air pollutants. These include substances such as particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen and sulphur oxides, which are emitted both in energy production and motorised transport. Some are greenhouse gases themselves, and all are harmful to our health with myriad effects on our lungs, blood vessels and even cancer risk. The cumulative impact of chronic exposure shortens lives and exacerbates a range of other medical conditions. Around the world, man-made outdoor air pollution accounts for an estimated 2.5 million excess deaths every year. Indoor air pollution (much of it from inefficient cookstoves) accounts for at least as many again, which means that overall air pollution is one of the leading killers globally. Lessons about how politics works… Given the clear evidence that air pollution from burning fossil fuels is so bad for health, combined with the urgency of tackling climate change, you might think governments would be rushing to capitalise on those win-wins. This is where the inflatable lungs come in. Whilst some countries are already taking the kinds of steps that we need, cutting emissions and simultaneously reducing air pollution, over the course of the talks it became fairly clear that some others are working very hard to promote a fossil-fuel dependent future. Almost all of the conference sponsors were fossil-fuel intensive industries. Even more astonishingly, just one day after a summit on climate change and health, organised by the newly-formed Global Climate and Health Alliance, the Polish Ministry of Economy hosted an “International Coal and Climate” summit in parallel with the COP. Feeling that this was outrageous, our team joined many other groups to take part in ‘Cough4Coal’: a public action staged outside the Coal Summit. The stunt involved a series of scenes alternating with speakers from Poland, the Philippines and the UK – one of our team – with the impressive accompaniment of a 7m tall pair of lungs. This was intended to be a visual symbol of the direct health impacts of burning fossil fuels, but also of the less direct health impacts of climate change. Tip of the iceberg

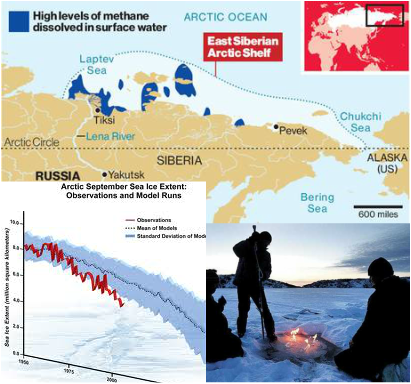

Climate change has been described as “the greatest global health threat of the 21stCentury” by the leading medical journal The Lancet. A 2012 analysis by the DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor arrived at a total of 400,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2010, the greatest burden within this being due to hunger and diarrhoeal disease. However, it is by no means clear that it is accurate to simply extrapolate the future burden due to climate change from the impacts seen so far. These may well be the tip of the iceberg, given that we’ve only seen limited warming relative to what is projected for the coming century. What are the main health impacts of climate change? They range from increased heat exposure, a particular problem among older people and manual labourers, to extreme weather events (which can often affect mental health particularly severely). Changes in the distributions of infectious diseases, and malnutrition and/or starvation due to effects on food production, are equally important. The indirect impacts, such as exacerbation of poverty, migration, and conflict, are both harder to attribute to climate change and significantly harder to forecast. Such impacts are likely to be non-linear and could well be very large indeed – especially with the levels of warming scientists are currently projecting in business-as-usual scenarios. For those interested in finding out more about the health impacts of climate change, we've compiled a summary here. Bridging the gap There may also be pragmatic reasons for framing climate change as a health threat; namely that it connects to people’s own lives and the things they value. In a 2012 study by Teresa Myers and colleagues, a test audience was presented with articles that discussed climate change from a range of different perspectives. Right across audience segments, the articles emphasising the health frame were more likely to elicit strong support for mitigation and adaptation policies than those focusing on the environment or national security. The second working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s fifth assessment report will include a substantial chapter on human health, which could present a useful opportunity for more public communication about climate change using the health frame. It is clear that the stakes are high for health if we continue on our current path. The evidence that action on climate change can benefit public health in all regions is strong – and growing. Emphasising the health implications of climate change can be a powerful way to engage a wider audience in the issue, and everyone with an interest in human health, or just the future of our planet, has a role to play. Not to suggest that you’d need to carry any giant lungs in front of government departments – though by all means get in touch if you’d like to…  Izzy Braithwaite From a BMJ Blogs series for the upcoming CleanMed Europe Conference - edited version at: http://bit.ly/13EBL8D The concept of sustainable healthcare and – related to that - how environmental change affects health are not generally taught in medical schools, but I was lucky enough to take part in a student-led national programme on the topic in my first year. I had long been interested in global health and the environment, so was keen to find out more and get involved in this area. The focus of my work has been with the Sustainable Healthcare Education (SHE) Network, for example contributing to a set of downloadable teaching resources and subsequently helping to collate a set of case studies on existing student-selected components. I’ve also been involved in the most recent project on curriculum learning outcomes, organised in response to a request from the GMC, which has been a multi-stage consultation process. The three overarching learning outcomes proposed on the basis of the consultation are to be published online soon and cover: the relationship between the environment and health; the environmental sustainability of health systems; and the ethical and policy-related issues that arise from understanding these two topics, such as how the duty of a doctor to protect health applies to future generations. As I‘ve read more about our impacts on the environment, climate science and the extent to which human health depends on ecosystems and climate stability, I’ve been surprised and concerned by how little of this information seems to reach the general public, including medical students. To help change that, I’ve been running workshops and campaigns with a student group called Healthy Planet UK, in partnership with a larger network called Medsin. Medical educators, students and clinicians wishing to set up more teaching in their medical school often encounter objections that there's not enough space in the curriculum or that these topics aren't relevant. Yet the evidence shows that climate change is an increasingly important threat to global public health, and I think the scope for health professionals to help shift political narratives around environmental issues is often underestimated. If my cohort of future doctors needs to know about tobacco or antibiotic resistance, then surely we also need to understand how changes to weather patterns and ecosystems are affecting, and predicted to affect, health. Equally importantly, we need to be aware of the growing evidence base around the opportunities, termed 'co-benefits', to deal with burgeoning public health problems such as obesity and poor mental health in a way that's synergistic with the goals of sustainable development. Given some of the details I had to learn in pre-clinical medicine, the argument that there's not enough space in the curriculum suggests it’s an issue of priorities. Do we really think enabling tomorrow's doctors to tackle what may well be a bigger health threat than tobacco - especially considering the complete inadequacy of the political response so far - matters less than learning, for example, all the steps of the Krebs cycle? My learning in this area has influenced the way I think about the rest of my education, and I think I'll be a better doctor for it; better able to understand the macro-scale influences on patients' lives, and to contribute to discussions about how health services could be better for both patients and the environment. To create lasting change - whether in sustainable healthcare, climate policy or other public health issues – tomorrow’s doctors require an understanding of the issues, to have had the freedom to discuss them and try out their ideas, and the skills for effective collaboration, including inter-sectorally. Through the SHE network, we are seeking to create this space for students to learn, reflect and debate about the issues, and to develop the skills to help lead the transition to sustainable healthcare. The fourth CleanMed Europe conference takes place at the Oxford Examination Schools from 17th-19th September, and Izzy will be talking about the SHE Network and Healthy Planet's activities during the conference. 18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.  Izzy Braithwaite A few weeks ago, I went to an Enough Food IF training day, organised by a number of the big organisations behind the campaign. It aimed to give us the background needed to visit our MPs to talk about two of the main asks – aid and tax – in advance of the Budget and the Finance Bill. The question the IF campaign asks is ‘IF we produce enough food to feed everyone, why do one in 8 people go hungry?’ The crux of the argument is that IF we can change a number of key things about our current system, we can make sure everyone gets enough to eat. I couldn't really argue with that, and I decided I wanted to meet my MP about it - which I did as part of a group on Friday afternoon, and really enjoyed. How is the campaign linked to climate and health? I’ve been interested in global health for several years, focusing more recently on how climate change affects, and will affect, global health, which is how I got involved in Healthy Planet. It seems to me that one of the big impacts climate change is having on people in the poorest countries – and one of the biggest effects it’s likely to have on health in the future - is through food. It makes a lot of sense to me that IF we can build a fairer food system, including through changes in the way tax works for developing countries, that will help reduce the impact of climate-induced crop losses on the health of the poorest. Although the Enough Food IF campaign doesn’t focus explicitly on climate change, there’s a fair amount of evidence that land grabs, food price speculation and short-sighted biofuels policies – all of which the campaign aims to highlight and tackle – act alongside more unstable weather and inadequate social security to push more people into food insecurity. But even if it weren’t for climate change, we have massive injustices around food and access to it; climate change just exacerbates them. You can't really disagree that a world in which almost a billion who don’t have enough to eat while so many others throw away as much as they do, and while so many people are suffering the health effects of obesity, is kind of crazy. Tax and development I didn’t know a lot about the ins and outs of tax policy and how it related to international development before getting involved in the IF campaign, but came away from the training day and my reading online afterwards with a better understanding. I learnt how crucial tax revenue is in enabling developing countries to finance public services, and had no idea that tax avoidance currently costs them to the tune of 3 times as much revenue as they receive in aid each year. I was shocked to learn how Associated British Foods, which produces vast quantities of sugar in Zambia – a country where many people struggle to afford enough to eat – has managed to ensure that it pays less tax in Zambia than the woman in this ActionAid video, a shopkeeper who sells their sugar. Then there was the story about the Rwandan revenue authority, set up with a grant of £24 million from DfID, which now generates that much in tax every 3 weeks. Talk about value for money. That revenue stability enables the Rwandan government to finance essential public services like schools and healthcare, and helps it to ensure that it’s people have enough to eat. If we want aid to be effective and countries to be able to finance aspirations like Universal Health Coverage, tax should be a global health priority, and it was great to have some real examples to illustrate that at the meeting.  The meeting Alison Marshall, who works at Unicef UK and had signed up as a coordinator for my borough on the online lobbying forum, managed to set up a meeting with my MP Jeremy Corbyn for yesterday afternoon, and put everyone who’d expressed an interest in touch with the other interested people in Islington North. About half of those on the email list were able to make it, with quite a range of ages, jobs and backgrounds. Most of us had never met one another before the meeting, so we divided up tasks and subjects in advance and turned up for a chat half an hour before. Unforeseen circumstances meant the office was unavailable that day so we had to relocate, but fortunately an incredible woman called Theresa had offered up the nearby Finsbury Park Community Centre for the meeting. She filled us in on what things are like in the ward, which is one of the most deprived in England, and it was sobering to hear some of the statistics and stories. I'd read a bit about Mr Corbyn’s voting record and past involvement in international development-related work, so I had thought he would probably be happy to support the 0.7% aid goal, but I hadn’t known how he’d respond to the ask on tax transparency, which is a relatively technical one and took more explaining. It relates to the upcoming Finance Bill, and specifically asks that it extends DOTAS (disclosure of tax avoidance schemes) rules to any which impact on developing countries, in order to help them tackle tax avoidance by multinational corporations operating in their countries. The DOTAS regulations help tackle corporate tax avoidance in the UK, and it essentially requires companies to disclose any schemes they use to get out of paying tax. The IF ask (briefing here) is to introduce a similar requirement for UK companies and wealthy individuals to report their use of tax schemes with an impact on developing countries. It also asks that the bill require that when such schemes are identified the UK will use its existing powers under bilateral and multilateral treaties to notify developing countries’ tax authorities, and to assist in the recovery of that tax. Of course, transparency doesn’t in itself prevent tax avoidance, but it does make it much easier to hold companies accountable, and helps to enable developing countries to enforce and improve their laws. And of course UK action is not the whole of the answer – that will include international cooperation, which hopefully the G8 will make progress on, and country-by country reporting amongst other things. But it would be a good step on the road towards a fairer and more effective tax system, and could potentially set a useful precedent for other countries, and the EU, to follow. I quite like a challenge, so I’d kind of hoped we’d have to argue our case a bit more, but in fact he was very much in agreement with both of our asks, and agreed to write to the Chancellor and to lobby other Labour MPs and to raise it after the Budget and the Finance Bill. I suppose I can hardly complain that I have an MP who cares about international development and takes an interest in the details of how we should contribute to it even though most of his time is spent dealing with much more local issues. He told us about some of the problems he'd been trying to fix recently, such as the story of a guy who’d been sleeping on a bus for months who he’d just spent the afternoon trying to get re-housed. I hadn’t really thought there would be many parallels between politics and medicine before the meeting - not least because doctors tend to be trusted by the public whereas many politicians aren’t - but if I'd had to guess his job without knowing, I could easily have guessed a doctor or an overworked social worker. Both are both more of a lifestyle choice than a nine-to-five job, and both doctors and politicians have the opportunity to change peoples’ lives for the better.  Now is when the real test for the campaign begins - making sure there's enough pressure, and enough other MPs on board - to push through specific reforms. Which is where you come in... How can you get involved?

|

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed