|

Alicia Pawluk Negotiations in the United Nations can often be lengthy and complex. For a succinct summary of today's negotiations, please view the overview below.

0 Comments

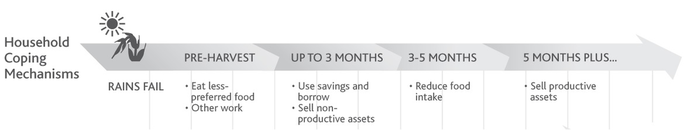

Alicia Pawluk Implementation of adaptation and mitigation measures is reliant on strong financial commitments. Therefore, developed countries are called upon to contribute to adaptation measures for developing nations. Below is a transcript from the COP 19 High-Level Ministerial Dialogue on Climate Finance, which discusses some of these issues.  Image source: UN_Spokesperson on twitter (click for link) Image source: UN_Spokesperson on twitter (click for link) Ricardo Tavares Da Costa This event was probably the highlight of the COP so far. At the start, the Prime Minister of Poland, Donald Tusk, addressed the audience, underlining the delicate and complex environmental issue we are trying to deal with in this conference. He argued that mitigation should not be associated with high costs, and that shale gas might be a sustainable solution. The audience was not impressed. The Secretary-General of the United Nations, Mr. Ban Ki-Moon, started by presenting his condolences to the Philippines, and emphasising the urgency of action: 'the climate science is clear and that we must rise to the challenge. The scale of our action is still limited, but there’s hope and opportunity. We need to reduce our footprint and walk towards carbon neutrality. Our targets must be bolder and we must send the right policy signals for investment. Plan not only for your country but for your neighbour and your neighbour’s neighbour, for your children and your children’s children'. Leadership John Ashe, President of the UN General Assembly, spoke next: "We in this room, the UN family, must reach a deal by 2015 and we cannot ignore the need for real implementation and progress. There is currently a wealth of knowledge and experience to limit emissions. We have good solutions, but we need to deploy them faster. Outside this room the world is becoming increasingly frustrated by the pace of these negotiations. Why are we not fulfilling our roles as leaders? Push back and say yes! We will act today! Right here, right now! Do not do it for yourself, do it for the present generation and for the ones to come". The Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Christina Figueres, spoke next, with characteristic passion: "The Conference of the Parties must respond to the need for climate action and we have a strong case for it (e.g. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). We need to focus on what is feasible and necessary and we need courageous leadership. I know you can, I know we can, so let us do it. Equity The President of Tanzania Mr. Jakaya Kikwete followed: "Africa suffers more than any other continent, despite having the smallest carbon footprint, less than 1t/year and not likely to exceed 2t/year by the end of 2030". This is a key point in terms of health equity: those least responsible are those who's health is most vulnerable to, and most affected by, climate change. This is of course also true in terms of future generations, a point which has been highlighted by extensive work on intergenrational equity by YOUNGO, but this area is still largely absent from draft texts. It is clear that there is a strong and urgent case for action, and that equity needs to be a central part of the agreements made. Now we must push hard to ensure that real and meaningful progress is made in the last week of the talks, and in the next two years leading up to 2015. Alicia Pawluk Whilst negotiators struggle to come to a consensus, time is slowly running out at COP 19. Healthy Planet UK has made many excellent contributions to the climate meetings, and has had the opportunity to listen to many world leaders. In order to get an idea of what a typical day would be like, we've attached our daily summary below. Please follow us on twitter @HealthyPlanetUK to get more regular and detailed updates!  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. It has been quite an experience being out in Warsaw for the climate summit so far, both good and bad - and very tiring! The first week at COP19 was spent mostly finding our feet in Warsaw and at COP19 (the national stadium is a maze!), getting our heads around the negotiations - and just how visible the corporate influence is, with sponsors ranging from coal to car and aviation companies, taking the term greenwashing to an entirely new level (could be a strong case for something similar to Article 5.3 of the WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control here, we think!) We've also had the chance to meet and talk to members of the UK government delegation, from both DECC and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, thanks to our friends over at UKYCC, which was particularly interesting. And we found ourselves in shock - and anger - after the irresponsible moves backwards on climate domestically by both Australia and Japan, especially coming just after the Philippines' lead negotiator Yeb Saño's historic and very moving speech about the devastation wrought by Typhoon Haiyan and his announcement that he was going on hunger strike for the duration of the talks unless there was meaningful progress.  The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action On Monday, we took part in 'People Before Coal', a protest action outside the Ministry of Economy who were - outrageously - hosting a 'Coal and Climate' Summit during the second week of COP19. Perhaps 'coal versus climate' would have been more accurate if you take a look at the World Coal Association's 'Warsaw communique'... Although the fact that the summit was taking place at all is a travesty, the demonstration was a colourful and exciting gathering of people from all over the world; speakers from Poland via the UK to the Philippines and many participants from all over Europe, gathered to highlight the health impacts of coal, on both people and the planet - with these amazing giant inflatable, breathing lungs (!) which were made by #Cough4Coal. There were three scenes in total, showing that the dirty energy future the coal industry's lobbyists are trying to sell us with their Coal Summit is not the clean, healthy future we want. As Christiana Figueres put it at the Summit, "we now know there is an unacceptably high cost (from burning coal) to human and environmental health".  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Along with some of our friends from the International Federation of Medical Students' Associations (IFMSA), we took up the role of young health professionals enthusiastically, with one of our delegation speaking in the gap between two of the scenes about how coal impacts health - both through the air pollution it creates, and through the health impacts of climate change. Some of our photos from the stunt are on the right, with more here; there's also a great blog from 350.org here. One of the best things about COP19 has been the chance to connect up with and talk to other young people from around the world, many of whom have gone to great lengths to fundraise to come and overcome immense obstacles in their fight for climate justice - although our backgrounds and organisations are different, we share a common cause. And it is clear that our governments are currently making nowhere near enough progress towards a binding deal that will keep the planet below dangerous temperatures which would pose a major threat to health. The last few days are likely to focus mainly on Loss and Damage, but - as Yeb Sano has eloquently reminded us - it is essential that we don't lose sight of the ultimate point of the UNFCCC, which is to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate change. At present, the vested interests that rear their heads through 'fossil-friendly' governments like those backing down on climate ambition, are still succeeding in delaying that process for as long as possible.  Tim Dobermann Increased food insecurity resulting from climate change is a big threat to many individuals living in the developing world, and likely to become increasingly so, especially with inadequate action on mitigation, as we're currently seeing. Unfortunately, the inequality of climate change means we will see the greatest health impacts falling on the world’s poorest – and those least responsible for the problem. Naturally, agriculture is a key issue for many parties here at COP. For much of Africa and South Asia, the incomes and health are directly linked to the yields of their crops. Moreover, it is one of, if not the most, climate-sensitive sectors. That agriculture can play a key role in both adaptation and mitigation - and that they need to be integrated better - has been a common theme voiced in many events thus far. Better management practices and techniques such as conservation tillage or proper application of fertilisers can both reduce emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (among others) and improve the resilience of smallholder farmers in the face of climate change – and so help to protect against malnutrition. Frustrations and setbacks Unfortunately, in a late night (or more accurately early morning) session of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), it became clear that no formal progress on establishing a working group or body to focus on agriculture would be made. Perplexing to those outside the negotiations – but, as it seems, entirely normal within them – is that all sides agree on the importance of raising efforts into climate-smart agriculture, yet no substantial agreement can be found and so it has had to be pushed to the agenda for COP20 in Lima next year, to many Parties’ and NGOs' dismay. Farmers and their families deserve so much better. Silver linings However, there is some good news amongst the largely frustrating negotiations. Comparatively little attention has been given to the advancements thamade in reducing emissions through deforestation and land degradation (REDD+), where the plus represents considerations about biodiversity and local and indigenous communities’ rights. Forests serve as natural ‘carbon sinks’, which take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen through photosynthesis. Parties have quickly recognised these benefits, and have readily moved towards mechanisms which can help to incentivise and implement these types of projects. Brazil has made significant leaps in reducing its emissions by combating deforestation; much could be gained by supporting other developing countries such as Indonesia to do the same, although the surge in global demand for palm oil of recent years poses a major challenge for REDD+ - and for climate and biodiversity. What now? The next few days see the start of the ‘high-level segment’ of the UN climate talks, where ministers and heads of state arrive to flex their political muscle in the negotiations. This next week should be seen as an opportunity to bring forth practical and comprehensive steps forward in the lead-up to a potential 2015 agreement in Paris. Genuine progress can be made on the issues concerning climate finance, ambitions for mitigation, and loss & damage. It is clear that no big agreement will be reached in Warsaw, but this does not prevent it from laying out a solid framework to build upon in Lima, when the Parties meet next in 2014, and in Paris in 2015.  Gabriele Messori Typhoon Haiyan has dramatically brought the human cost of climate extremes before the eyes of the world. Here at the United Nations climate negotiations in Warsaw, the impact of the typhoon was echoed by a passionate speech from the delegate of the Philippines, Yeb Sano. In most geographical areas, climate change will lead to increasingly severe climate extremes. The nature of these extremes largely depends on the region of interest. While South-East Asia is prone to devastating typhoons, other regions are crippled by droughts. All these have devastating effects on public health, seriously compromising food security. There is therefore a strong need for an international mechanism addressing the losses and damage caused by climate extremes. A loss and damage agreement is currently being negotiated at the United Nations Conference of Parties, but the starting positions of many countries are radically different. While the developing countries push for a new mechanism dealing specifically with loss and damage, the developed countries speak of strenghtening existing mechanisms and bodies. Some countries, notably the U.S.A., also ask for loss and damage to be discussed in the framework of adaptation to climate change as opposed to as a separate mechanism. The question of liability for damage due to climate change is also a very contentious point. The U.N. negotiations are central to the matter, and need to provide a global coordination for tackling loss and damage. However, this does not mean that parallel approaches should not be developed. While the negotiations continue, the African Union has established a new specialized agency called the African Risk Capacity (ARC). The ARC is an extreme weather insurance mechanism designed to overcome the current ad-hoc disaster relief system. Countries will be able, by paying a premium, to insure themselves against drought-related damage. It is envisaged that the Capacity will be extended to other climate extremes in the future. The design of the Capacity and its current focus on droughts means that it has important co-benefits relating to public health. Research into household coping mechanisms has shown that droughts in Africa typically lead to a reduced food intake within a few months of the rains failing (typically 3-5 months, see infographic below). This can be averted if aid is received before this time. The objective of the ARC is for assistance to reach the designated areas within 120 days, meaning that the food security of the affected communities would be largely guaranteed.  Household coping mechanisms in the aftermath of a drought, courtesy of ARC. Currently, over 20 countries have signed the establishment treaty of the ARC. The mechanism will soon be operational, and has the full potential to become a leading example of international loss and damage mechanism. As with any project involving humanitarian assistance, the financial efficiency of the operation is crucial to its success. Projections indicate that the fast response mechanism on which the ARC is based would be over three times more effective per dollar spent than ad-hoc aid received after a crisis has unfolded. This is particularly true in those african countries where rain-fed agriculture employs a significant portion of the population. Regarding the scientific implementation of the project, the data collection is based on a satellite weather-surveillance system. An algorithm then translates the data collected into a risk and damage profile for each country, allowing for a precise value to be attributed to both the country's premium and its financial needs relative to a specific drought event. Currently, over 20 countries have signed the establishment treaty of the ARC. The mechanism will soon be operational, and has the full potential to become a leading example of international loss and damage mechanism.  Isobel Braithwaite Published in Outreach magazine at http://www.stakeholderforum.org/sf/outreach/index.php/previous-editions/cop-19/193-cop-19-day-3-climate-change-and-health/11583-climate-and-mental-health-impacts-and-inequalities The health impacts of climate change, and the importance of integrating health into adaptation planning, have become increasingly prominent in recent years - though arguably not prominent enough. For example, there have been several declarations from health organisations – the World Health Organization (WHO) has this year trained a number of Ministers of Health in climate policy, who are attending in their country delegations – and many adaptation initiatives now prioritise the health sector. Often the health impacts which are highlighted are things like heat deaths, malnutrition associated with food insecurity, changing distributions of infectious diseases, such as dengue fever, and the direct deaths and injuries caused by extreme weather events. All are important, and are likely to pose a significant threat to health – especially without an ambitious and equitable global deal, and successfully closing the pre-2020 emissions gap. What is less often considered, but equally important, is that climate change not only affects physical health but also mental health – and is likely to impact on mental health dramatically. It matters because of the immense detriment to people’s wellbeing, and because the other impacts of mental health are wide-reaching. There are knock-on effects on physical health and life expectancy, people’s ability to work and to participate actively in their communities, and of course on healthcare costs. After climate-related disasters such as floods, tropical storms and forest fires, affected communities have been documented to suffer rates of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many times higher than 'control' communities with similar socioeconomic conditions and baseline levels of mental health. For example, a 2001 study by Dr. Armen Goenjian and colleagues after Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua found that estimated rates of PTSD and/or depressive disorders in the worst-affected town of their study, Posoltega, reached 80-90%, compared to levels around a third as high in the least severely affected town, Leon. Slow-onset crises, such as those caused by droughts or sea-level rise, can also impact mental health adversely, and uncertainty about the future is a particularly important factor. At present the evidence base on the mental health impacts of disasters is sparse, because of the difficulties associated with conducting rigorous research in disaster contexts, the complexities and ambiguities that surround mental health in general, and the fact that – legitimately – research is not an immediate priority after a major disaster. However, the evidence we do have shows that the effects can last for months to years, and effective strategies exist to support mental health after disasters. This is of course a complex subject but evidence seems to suggest that the best approach is not necessarily to provide counselling for those affected, but instead to focus on resolving the main causes of distress, such as the need for shelter, social support and medical care, and in the longer-term, support to rebuild. The opportunity to rebuild elsewhere, or to migrate, can also be important, including to reduce future risks, and can be a form of adaptation – especially for those affected by sea-level rise or desertification for instance. This issue has not yet been adequately addressed by the UNFCCC framework or other international institutions. Mental health is already a major challenge in global health today, and it is rising. By creating the concept of a 'Disability-Adjusted Life Year' (DALY; comprised of years of life lost and years lived with disability, where weights are applied), the Global Burden of Disease project has enabled us to compare a wide range of conditions in terms of ‘healthy life years lost,’ including those which are generally non-fatal, such as mental health conditions, into priority-setting. According to the latest assessment in 2010, major depressive disorders have risen to become the second highest cause of DALYs lost worldwide; anxiety disorders are close behind. In both women and younger age groups, both rank higher still. Both are also particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, particularly in the poorest communities: climate change creates a doubly uneven playing field for women’s and young people’s mental health. We also know that the levels of mental distress and conditions such as PTSD seen after disasters are influenced by factors such as the severity of the event, the damage caused, the existence of effective relief systems, and access to funds to enable people to rebuild their homes and for communities to recover. As well as strengthening the case for investment in adaptation, this is highly relevant to the ongoing discussions around Loss and Damage at COP 19, and – as the science of climate change grows stronger; the task of mitigating it ever more urgent – it is essential that wealthier countries, who have benefitted from their early industrialisation, support those who have contributed least to climate change to cope with and recover from its’ impacts. More references and links: http://climate.adfi.usq.edu.au/statements/74/  Loss and damage highlighted on the first day at UN Climate Talks Tim Dobermann, Healthy Planet COP19 delegation "I will voluntarily refrain from eating food during this COP until a meaningful outcome is in sight,” announced the Philippine lead negotiator Yeb Sano today. This was in the opening session of the 19th Conference of the Parties (COP19) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Warsaw, Poland. Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest typhoon on modern record, slammed into the Philippines and much of South-East Asia late last week. So far, anestimated 10,000 have died, but it is likely that the final toll will increase as the Philippines cleans up the destruction left in the typhoon’s wake. In the opening session, Mr. Sano gave a passionate plea for us to “open our eyes to the stark realities we face” and to come together to make significant progress on a global deal covering mitigation, adaptation and finance for developing countries. Devastating storms like this are becoming more common. We cannot attribute a given extreme event to climate change with certainty, but they form part of along-term trend of more severe storms, heatwaves, floods and forest fires, and are consistent with the IPCC's predictions.

On the other hand, many developed countries are worried that loss and damage payments could easily spiral out of control, and that they may weaken incentives for countries to invest in adaptation efforts. Both are probably correct. Loss and damage – an issue that has only very recently emerged on the negotiating scene – will require an international body to determine the extent of losses as well as to spread reparation responsibilities in an equitable manner.

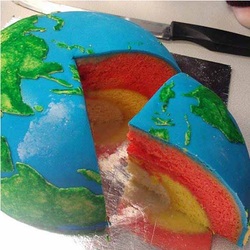

Much of this year’s climate negotiations will be focused on establishing the framework for a post-2015 deal, designed to be agreed upon when countries meet in 2015 in Paris. In this sense, there may not be many ‘big outcomes’ from the negotiations. However, given recent events and a considerable degree of attention, there is potential to make rapid progress on loss and damage over the next two weeks. Having been fortunate to call the Philippines home for 16 years, it truly saddens me to see this continual suffering. Mr. Sano fully embraces his role not only as a diplomat or a proud Filipino, but as a representative for all of those on this planet who will directly feel the effects of climate change. The human cost of climate change is real, and it has never been clearer. It is a shame that we are in a situation where Mr. Sano needs to resort to a hunger strike to communicate the seriousness of these issues. All of society – NGOs, governments, the public – must take this message and respond. I hope that we will remember these next two weeks as the time when a brave man took a stand, to which we, finally, responded. By Connor Schwartz  Emissions rights. Who deserves the biggest slice? Emissions rights. Who deserves the biggest slice? In part one we laid the groundwork of theory upon which to build a climate regime which recognises the entitlement of all to the dignity and respect of a life that is fully human. Now I would like to begin to flesh out what such a regime demands of our approach to climate change and our distribution of the burdens associated with solving it. First of all, health. Although not indexed, it is clear that health is one of the most vital capabilities we are entitled to. Climate change has far reaching distributive effects for global health if we choose to do nothing, but so too do our possible attempts to mitigate and adapt to it. The messages from Sen and Nussbaum are clear. Allowing climate change to continue unabated will harm our entitlement to adequate health gained by our species membership, therefore seriously contravening the demands of justice. Furthermore, the way we respond to climate change must be in accordance with the promotion of global health to all of the world’s people and not to the detriment of it. Sounds just so far. Secondly, emissions allocation. GHG emissions, if we are to mitigate the effects of anthropogenic climate change, are a resource and therefore must follow a distribution. We can think of the “safe level” of emissions that we can emit and still prevent runaway climate change as a huge cake. This cake is thought to have been about 1 trillion tonnes in 2009, in order to remain below a 2 degree warming on pre-industrial levels. Mmmm, delicious emissions cake. Well one of the key jobs of the UNFCCC is to divide up that cake while all the countries of the world ask hungrily for a decent slice. Under a capabilities analysis, the current distribution of the cake has got to change. At the moment, people in Australia, the USA and Europe scoff their slices while driving SUVs, eating meat and jumping on short haul flights. Meanwhile, those in the developing world cannot scrape together the crumbs to industrialise their domestic agricultural practices and ease food security crises. This contravenes seriously the demands of justice. I think we can go further still. I would argue that the costs of mitigating and adapting to climate change should be distributed according to the levels of emissions that have not been used to secure basic capabilities. Since we are each entitled to our basic human capabilities, we can lay no blame for emissions used to provide decent healthcare, adequate education, ensure the empowerment of women, secure equal political rights, etc. We can lay blame, however, for emissions used to provide luxury while the planet plunges into climate crisis. One final point on capabilities for any who are still with me. Any distribution found in a climate change regime, and there are many, seems appropriate for analysis as a distribution not of the resource but of human capabilities. Any, that is, except for one. As the effects of climate change begin to come about, and the extent of the effects we have already “locked in” to our climate system are realised, an area of growing importance is compensation for negative effects – known as “loss and damage” within the UNFCCC. This area of negotiations is likely to be a significant part of the focus for COP19 just around the corner, and a main focus for NGOs in attendance. So what to make of loss and damage within a capabilities framework?  The explosion of climate refugees is a tragedy beyond measure. The explosion of climate refugees is a tragedy beyond measure. It is hard to reach any conclusions at all. Recall that the cornerstones of the approach were that human goods were neither aggregable nor fungible. That we just can’t make sense of capabilities having a value in terms of anything other than themselves. Financial compensation for the loss of capabilities does not a just situation make. They are simply qualititatively different. The most we seem able to say is that the situation in which someone is forced from their own environment by environmental factors caused by those on the other side of the world is unbelievably tragic and should never have happened. Although undoubtedly true, this expression of sadness doesn’t seem of any practical use when faced with the reality of millions of climate refugees, of the loss of political freedoms as resource wars are waged, and of backsliding in gender equality when female-dominated industries such as agriculture suffer in the hands of climate crisis. Well then, what else can we say? We can say that compensation paid to nation states without directions on what the money is for is morally wrong. It doesn’t matter how many millions we give to Bangladesh for their climate damages, if there are people without replacement homes that they feel comfortable and safe in then justice has not been served. Any lost capabilities therefore must be compensated for in kind. For example, environmental refugees must be provided property rights on an equal basis with others in the countries in which they settle, and political rights to have an equal say in how they are governed. Those whose diets are disrupted by the effects of climate-related extreme weather events on agricultural yields must be recognised as having an entitlement to the provision of adequate nutrition as a minimum requirement of justice. So, all in all, this is just one approach at a robust theory of climate justice and just one provision for a just climate regime. Fundamentally I think, if imperfect, it starts us down the right track. We must recognise that climate change not only has the potential to exacerbate inequalities when left unchecked, but also when solved inequitably. We must refuse to equate human good to a monetary value and reject the politics of self-interest. We must recognise the entitlement of all to adequate health, and the dignity and respect of a life which is fully human. There is no reason why my answers are more valid than yours, but it is vital that we keep trying to provide them and never fail to ask the questions. We have a colossal challenge ahead of us in mitigating, adapting to, and compensating for anthropogenic climate change. But we must embrace justice as we move forward. The wrong solutions threaten to do as much damage as none at all. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed