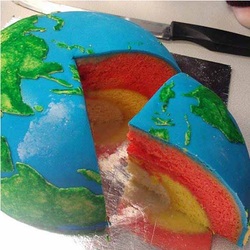

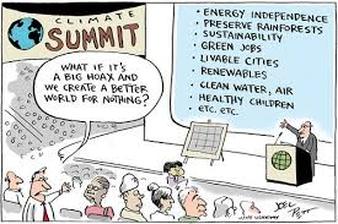

By Connor Schwartz  Emissions rights. Who deserves the biggest slice? Emissions rights. Who deserves the biggest slice? In part one we laid the groundwork of theory upon which to build a climate regime which recognises the entitlement of all to the dignity and respect of a life that is fully human. Now I would like to begin to flesh out what such a regime demands of our approach to climate change and our distribution of the burdens associated with solving it. First of all, health. Although not indexed, it is clear that health is one of the most vital capabilities we are entitled to. Climate change has far reaching distributive effects for global health if we choose to do nothing, but so too do our possible attempts to mitigate and adapt to it. The messages from Sen and Nussbaum are clear. Allowing climate change to continue unabated will harm our entitlement to adequate health gained by our species membership, therefore seriously contravening the demands of justice. Furthermore, the way we respond to climate change must be in accordance with the promotion of global health to all of the world’s people and not to the detriment of it. Sounds just so far. Secondly, emissions allocation. GHG emissions, if we are to mitigate the effects of anthropogenic climate change, are a resource and therefore must follow a distribution. We can think of the “safe level” of emissions that we can emit and still prevent runaway climate change as a huge cake. This cake is thought to have been about 1 trillion tonnes in 2009, in order to remain below a 2 degree warming on pre-industrial levels. Mmmm, delicious emissions cake. Well one of the key jobs of the UNFCCC is to divide up that cake while all the countries of the world ask hungrily for a decent slice. Under a capabilities analysis, the current distribution of the cake has got to change. At the moment, people in Australia, the USA and Europe scoff their slices while driving SUVs, eating meat and jumping on short haul flights. Meanwhile, those in the developing world cannot scrape together the crumbs to industrialise their domestic agricultural practices and ease food security crises. This contravenes seriously the demands of justice. I think we can go further still. I would argue that the costs of mitigating and adapting to climate change should be distributed according to the levels of emissions that have not been used to secure basic capabilities. Since we are each entitled to our basic human capabilities, we can lay no blame for emissions used to provide decent healthcare, adequate education, ensure the empowerment of women, secure equal political rights, etc. We can lay blame, however, for emissions used to provide luxury while the planet plunges into climate crisis. One final point on capabilities for any who are still with me. Any distribution found in a climate change regime, and there are many, seems appropriate for analysis as a distribution not of the resource but of human capabilities. Any, that is, except for one. As the effects of climate change begin to come about, and the extent of the effects we have already “locked in” to our climate system are realised, an area of growing importance is compensation for negative effects – known as “loss and damage” within the UNFCCC. This area of negotiations is likely to be a significant part of the focus for COP19 just around the corner, and a main focus for NGOs in attendance. So what to make of loss and damage within a capabilities framework?  The explosion of climate refugees is a tragedy beyond measure. The explosion of climate refugees is a tragedy beyond measure. It is hard to reach any conclusions at all. Recall that the cornerstones of the approach were that human goods were neither aggregable nor fungible. That we just can’t make sense of capabilities having a value in terms of anything other than themselves. Financial compensation for the loss of capabilities does not a just situation make. They are simply qualititatively different. The most we seem able to say is that the situation in which someone is forced from their own environment by environmental factors caused by those on the other side of the world is unbelievably tragic and should never have happened. Although undoubtedly true, this expression of sadness doesn’t seem of any practical use when faced with the reality of millions of climate refugees, of the loss of political freedoms as resource wars are waged, and of backsliding in gender equality when female-dominated industries such as agriculture suffer in the hands of climate crisis. Well then, what else can we say? We can say that compensation paid to nation states without directions on what the money is for is morally wrong. It doesn’t matter how many millions we give to Bangladesh for their climate damages, if there are people without replacement homes that they feel comfortable and safe in then justice has not been served. Any lost capabilities therefore must be compensated for in kind. For example, environmental refugees must be provided property rights on an equal basis with others in the countries in which they settle, and political rights to have an equal say in how they are governed. Those whose diets are disrupted by the effects of climate-related extreme weather events on agricultural yields must be recognised as having an entitlement to the provision of adequate nutrition as a minimum requirement of justice. So, all in all, this is just one approach at a robust theory of climate justice and just one provision for a just climate regime. Fundamentally I think, if imperfect, it starts us down the right track. We must recognise that climate change not only has the potential to exacerbate inequalities when left unchecked, but also when solved inequitably. We must refuse to equate human good to a monetary value and reject the politics of self-interest. We must recognise the entitlement of all to adequate health, and the dignity and respect of a life which is fully human. There is no reason why my answers are more valid than yours, but it is vital that we keep trying to provide them and never fail to ask the questions. We have a colossal challenge ahead of us in mitigating, adapting to, and compensating for anthropogenic climate change. But we must embrace justice as we move forward. The wrong solutions threaten to do as much damage as none at all.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed