By Connor Schwartz  Amartya Sen ponders justice Amartya Sen ponders justice Climate ethics and climate justice are subjects which hide in the background of COPs and treaties, rarely given any limelight of their own. In fact, the most common appeal to climate justice within negotiations are false ones, nations setting out their stall while grasping furiously for some foundations to stand it upon. Because, while the neoliberal hegemony of self-interested actors fails miserably to encompass the breadth of human social relations, it is demonstrably accurate on an international level. Powerful nations may appeal to political theory and forms of justice to back up their positions, but you can bet that their move went outcome first, evidence second, and not the other way around. For example, in the early 2000s while America was resisting becoming party to the Kyoto Protocol, the Bush administration argued furiously that the Annex 1 countries were being unfairly asked to mitigate a crisis which, all things considered, it looked like other countries had a lot more to lose from than themselves. Slowing anthropogenic climate change will cost us a packet and only benefit Tuvalu, how unjust! It did not matter, of course, that this claim is justified only by a philosophy so libertarian that no US president (Nixon included) has ever come close to it. No, much more important to scream “injustice!” and hope nobody really notices that the argument doesn’t stack up. Thus climate ethics has been sullied and debased by negotiators wanting a transcendent justification for their greed. It’s time to put it back at the heart of a global climate regime. Here is just one such attempt. It’s not perfect but I think it reveals a few key things we are looking for from a global climate treaty, and provides the beginnings of a move away from pragmatism and towards justice. Hold tight, here comes the theory. (If you’re not interested in the theory in isolation, jump straight to part two where climate change comes back onto the scene). When we discuss distributive justice of any kind, the first thing to be argued over is what’s called the “metric” – what exactly it is we should be distributing. Let’s narrow our gaze to egalitarianism – that equality is, for some reason, at least partially good – as it is now almost universally accepted across the liberal democracies. There are two traditional camps in the metric debate: resourcists and welfarists. As their names give away, resourcists believe justice includes a focus on equalising the amount of stuff people have, whereas welfarists prefer a focus on the wellbeing or happiness people get from that stuff. It’s the classic means/ends debate. This division has been standing for hundreds of years, splitting radical feminists from their traditional colleagues and communists from conservatives. This impasse however was, I believe, broken in 1979 when Amartya Sen – a heterodox development economist from Bangladesh – gave his Tanner Lecture entitled ‘Equality of What?’. In this lecture Sen dismantled both metrics, each with a simple thought experiment, asking whether what each model was forced to conclude sounded much like justice or not. Number one. Take two agents: one able-bodied and another with a severe disability needing round the clock care. Equalise resources. After covering their care expenditure, the disabled agent has far less resources than the able bodied agent to increase their wellbeing with. Similarly other divides – gender, social position, country of birth, etc. – reach the same conclusion: that a resource egalitarian looks to be saying that justice permits, or even requires, that wellbeing is determined by factors of luck. Ask yourself: does that sound much like justice? Number two. Brian is a plumber living in the city of London and Vikram works as a dabbawalla, distributing Tiffins to the workforce of Mumbai. Brian, from any objective standpoint, enjoys a far higher standard of living than Vikram yet it is certainly conceivable that Vikram is the happier of the two. Empirically, what’s called “hedonic adaptation” shows us that as our income increases so too can our expectations, resulting in no greater happiness. So say Vikram is the happier of the two because he expects less, and we have some spare resources to distribute. We must be persuaded to give the extra to Brian. Justice? To say a poor person has no claim to extra resources because their expectations are lower doesn’t sound much like justice to me. So what does Sen suggest? Justice, he claims, is found in neither resources nor welfare, but some function between the two, some measure of how we can translate resources into welfare. The correct metric for distributive justice is a person’s capabilities or, to be specific, the capability to achieve particular substantive human functionings. Say what? Put simply, what justice demands is equalised are the real and tangible freedoms that humans can possess. It doesn’t matter how much income a person has, if they have no access to healthcare then they are not being served by justice. It does not matter how happy a person is, if they cannot access education then that is a failure of justice.  Martha C. Nussbaum Martha C. Nussbaum Although the language of capabilities was introduced by Sen, it was American theorist Martha C. Nussbaum that developed it into a robust philosophical doctrine. Borrowing from the young Marx, Nussbaum claims that justice provides entitlement to a plurality of values that are both non-aggregable and non-fungible. In other words, we cannot serve justice by simply giving all a certain amount of a certain thing – say, money – and then leaving them to make choices as to how they trade it. Rather, we must concentrate on fulfilling a range of indicators that are distinct and cannot be traded off against each other. Simplistically, one could not for example be compensated for an inadequate life expectancy by being allocated more political rights. This stands explicitly against classical and neoliberal theories of development, relying on GNP to assess the growth of a nation and the wellbeing its peoples. What’s more we do not have to earn these entitlements. They are derived from our entitlement to “the respect and dignity of a life that is fully human”. We possess them, therefore, merely due to our species membership. (Nussbaum also holds that it is likely many other species are similarly entitled to various capabilities, but for now we can just consider our entitlements on account of our being human.) That’s all well and good, but what on earth does it have to do with climate negotiations? Lots, actually. Part two focuses on bringing climate change back into the picture, and putting justice back at the heart of a global climate regime.

1 Comment

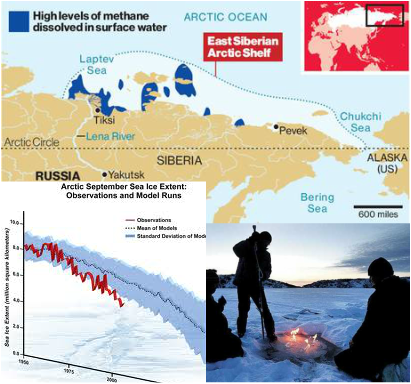

Alistair Wardrope, Healthy Planet Sheffield Originally posted here Would anyone dispute that healthcare systems ought to put their patients first? The mantra has a near-unassailable status in discussions of the best foundations for healthcare. The UK’s General Medical Council makes it first amongst the Duties of a Doctor; it provides the title of the Department of Health’s response to the findings of the Francis Report; and it lies (in its more-theorised form, ‘patient-centred care’) at the core of Don Berwick’s recent report into safety in the NHS. No politician, of any political stripe, would see fit to enter into a debate on health without it taking pride of place in their rhetoric. I’ve used it myself, campaigning for the priority of “patients before profits”. Nonetheless, I’ve long had qualms about it. It took a work of fantasy to figure out exactly why. During a recent and all-too-brief summer break, I decided to read China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station. I had harboured the vague intent of doing so for several years, but a fortuitous alignment of stars and an inability to access the books I was supposed to read in the university library meant I finally did. As a (somewhat lapsed) devotee of speculative fiction, I’d always expected to find more than simple escapism between its covers; however, I did not expect it to form the nucleus around which those nagging worries about patient-centred care would crystallise. The passage that set me thinking is little more than an aside, one of the short conversational detours the novel is littered with. It concerns a society of nomadic bird-people, the Garuda of Cymek. Garuda society is founded on the moral and political primacy of individual freedom. Their legal code admits but one crime – depriving another Garuda of choice; their ethical code, only one vice – disrespect. So far, so Tea Party. But the Garuda take these principles in an altogether different direction. Their interpretation of individualism rests on a particular understanding of what the individual is: the ‘concrete’ individual. As Ged, the autodidact librarian-priest, states: You are an individual inasmuch as you exist in a social matrix of others who respect your individuality and your right to make choices. That’s concrete individuality: an individuality that recognizes that it owes its existence to a kind of communal respect on the part of all the other individualities, and that it had better therefore respect them similarly. With the individual understood in these terms, disrespect becomes at heart a crime of ‘abstraction’: isolating one’s own individuality from the network of social interactions by which it and other persons are constituted and so losing the symmetry between them in which equal status is grounded. The Garuda share their ‘concrete’ understanding of the individual with a strong line of philosophers and political theorists. In his influential essay ‘Atomism’, the communitarian thinker Charles Taylor describes the individual as existing only when grounded in a society that affords the material, psychological and social resources for them to develop into freely-choosing agents, and provides the range of options necessary to make such choices meaningful. Respect for such individuals, therefore, is inseparable from respect for the social conditions underpinning their individuality. This is in stark contrast to the ‘atomism’ of the title, a charge he levels against the libertarian individual, whose values and preferences are interpreted and realised independently of others, and the protection of whose choices sets the boundaries of an acceptable social contract. These ideas are developed upon in recent work in feminist philosophy on ‘relational’ conceptions of autonomy. Traditionally, medical ethics has employed a rather thin understanding of autonomy – interpreted in the doctrine of informed consent, for example, as little more than decision-making capacity. Relational theorists argue that this ignores the role played by our emotions and attitudes towards ourselves and others – and their attitudes towards us – in developing and maintaining our capacities for autonomy. Consider an individual who, after a lifetime of oppression, comes to adopt those oppressive values as his own; the individual who does not have the necessary self-respect to consider herself worthy to make her own; or the individual who, like Aesop’s fox rejecting the inaccessible grapes as sour, comes to view certain ways of living as undesirable only because they are not realistic options available to them. In each case, the individual may be in full possession of the faculties that constitute mental capacity, but faces more subtle, relational, threats to their autonomy. The concrete individualism of the Garuda – and the work of communitarian and relational theorists – captures my concerns about patient-centred care. For in many interpretations of the term, the idea of the patient upon whom care is being centred is what the Garuda would consider an abstract individual. When patient-centredness merely means enhancing patient choice, increasing medical consumerism or a way to promote marketisation of health services, we present the patient as the isolated, rational ‘chooser’ that is the subject of Taylor’s ‘atomism’ critique. More generally, an interpretation of patient-centred care focussed solely on the clinical encounter – where it concerns only the interactions between health professionals and the individuals who come to them at the point of clinical need – risks leaving out other individuals and important aspects of care. When care is centred on the patient, who or what falls into the periphery? It seems to me that many who fall into the margins of this picture are those who are already most marginalised. Most obviously entering into this group are those who need health care but are unable to access it: ‘patient-centred’ care, focused on the abstract patient, has nothing to say about caring for those who – through legal, economic, social or psychological barriers to access – are unable even to become patients. But, even setting aside the tremendous injustice and inequity – where the most vulnerable communities, such as vulnerable migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, poor and oppressed groups, are done further harm –ignoring these groups is a public health disaster. Perhaps this could be remedied by defining ‘patients’ according to their need for health care rather than their ability to access it; but this picture still sees those patients as abstract individuals, and so has little room for public and global health concerns that make no sense in individualistic terms. Infection control, mitigation of climate change and its health impacts, social and political action on the social determinants of health: all are relational public goods. They are not focussed toward, or done in aid of, any individual patient, and only make sense at a population level. In the current political climate in the UK – where attempts are being made to limit access to healthcare for migrants, and such care is increasingly conceived of as a service provided to individuals for individual benefit – the rhetorical use of patient-centredness emphasises only the abstract patient, with the attendant dangers to public health sketched above. But the good news is that, when the individual is understood in concrete terms, these dangers are not just brought back into the fold – they become a central component of patient-centred care. The reason why is simple: the health of the individual simply cannot be considered in isolation from that of the population. As Sir Muir Gray writes, “personalised and population medicine are interwoven like warp and woof.” A healthcare intervention is never solely for a single, isolated patient; it is simultaneously a public health measure. So when the International Association of Patient Organisations puts patient involvement in social policy, universal access to health care, and attention to education, employment and family issues at the core of its definition of patient-centred care, it is not adding these in as an additional ingredient to aiding execution of the interests and desires of individual patients in the clinical setting. Rather, it acknowledges the former as a core component of the latter. And protecting and extending access to healthcare for migrants – economic, asylum seeker or undocumented – is not a good to be weighed against the health needs of a nation’s citizens, but an integral part of serving those needs. In meeting the challenges of shaping more environmentally sustainable health systems – able to meet the needs of people today without sacrificing those of future generations – we need not marginalise or ignore current patient’s interests; as elsewhere in healthcare improvement, “the greatest untapped resource in healthcare is the patient.” Such work on sustainable healthcare – the focus of this September’s CleanMed Europe conference in Oxford – is a re-interpretation of what patient-centred care could be, modelled on a more comprehensive understanding of what it means to be a patient. It turns out, then, that my concern is not primarily with putting patients first, or with patient-centred care – at least, not with what those ideals could and should mean. The problems arise only when the individual is considered in isolation from their social and political context and the environment around them. Given the fundamentally relational nature of health and disease, this isolation is intellectually and ethically untenable; patient-centred care makes sense only when we listen to the lesson I was taught by a fictional society – to view patients (ourselves included) as concrete, inherently social, individuals.  Izzy Braithwaite From a BMJ Blogs series for the upcoming CleanMed Europe Conference - edited version at: http://bit.ly/13EBL8D The concept of sustainable healthcare and – related to that - how environmental change affects health are not generally taught in medical schools, but I was lucky enough to take part in a student-led national programme on the topic in my first year. I had long been interested in global health and the environment, so was keen to find out more and get involved in this area. The focus of my work has been with the Sustainable Healthcare Education (SHE) Network, for example contributing to a set of downloadable teaching resources and subsequently helping to collate a set of case studies on existing student-selected components. I’ve also been involved in the most recent project on curriculum learning outcomes, organised in response to a request from the GMC, which has been a multi-stage consultation process. The three overarching learning outcomes proposed on the basis of the consultation are to be published online soon and cover: the relationship between the environment and health; the environmental sustainability of health systems; and the ethical and policy-related issues that arise from understanding these two topics, such as how the duty of a doctor to protect health applies to future generations. As I‘ve read more about our impacts on the environment, climate science and the extent to which human health depends on ecosystems and climate stability, I’ve been surprised and concerned by how little of this information seems to reach the general public, including medical students. To help change that, I’ve been running workshops and campaigns with a student group called Healthy Planet UK, in partnership with a larger network called Medsin. Medical educators, students and clinicians wishing to set up more teaching in their medical school often encounter objections that there's not enough space in the curriculum or that these topics aren't relevant. Yet the evidence shows that climate change is an increasingly important threat to global public health, and I think the scope for health professionals to help shift political narratives around environmental issues is often underestimated. If my cohort of future doctors needs to know about tobacco or antibiotic resistance, then surely we also need to understand how changes to weather patterns and ecosystems are affecting, and predicted to affect, health. Equally importantly, we need to be aware of the growing evidence base around the opportunities, termed 'co-benefits', to deal with burgeoning public health problems such as obesity and poor mental health in a way that's synergistic with the goals of sustainable development. Given some of the details I had to learn in pre-clinical medicine, the argument that there's not enough space in the curriculum suggests it’s an issue of priorities. Do we really think enabling tomorrow's doctors to tackle what may well be a bigger health threat than tobacco - especially considering the complete inadequacy of the political response so far - matters less than learning, for example, all the steps of the Krebs cycle? My learning in this area has influenced the way I think about the rest of my education, and I think I'll be a better doctor for it; better able to understand the macro-scale influences on patients' lives, and to contribute to discussions about how health services could be better for both patients and the environment. To create lasting change - whether in sustainable healthcare, climate policy or other public health issues – tomorrow’s doctors require an understanding of the issues, to have had the freedom to discuss them and try out their ideas, and the skills for effective collaboration, including inter-sectorally. Through the SHE network, we are seeking to create this space for students to learn, reflect and debate about the issues, and to develop the skills to help lead the transition to sustainable healthcare. The fourth CleanMed Europe conference takes place at the Oxford Examination Schools from 17th-19th September, and Izzy will be talking about the SHE Network and Healthy Planet's activities during the conference. 18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.  The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) Izzy Braithwaite Originally published at: http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/comment-health-overlooked-in-our-response-to-climate-change/ The protection of human health and wellbeing is a central rationale for the emissions reductions called for in the very first article of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Yet, somehow, the issue is missing from many parts of the UN talks. The growing body of research and evidence in the area over the past couple of decades hasn’t really translated into a broader understanding of how climate change and health are related, beyond a relatively small community of academics and health professionals. Knowledge about the links between climate and health among the public, climate negotiators and environmentalists is often limited and quite superficial. It typically doesn’t stretch far beyond the more direct impacts, such as heatwaves, vector-borne diseases or extreme weather events such as flooding. Indirect effects on health are rarely considered, and both the media and the public tend to frame the impacts of climate change in terms of the risks to ecosystems and species or economic losses; very rarely in terms of its other impacts on people and their health. Perhaps this is part of why climate mitigation and adaptation measures fail to get the levels of both political and financial support they need to tackle climate change and to protect and promote health in the face of it: current levels of adaptation finance, much like current emissions reductions pledges, are grossly inadequate. As a glance at any newspaper or polls about the relative political importance of different topics make clear – most of us are concerned about our own health and the health of those we care about, including that of our children and grandchildren and less visible problems like climate change, which are also delayed in time, often feature far below this on the agenda. Climate change will dramatically affect the health of today’s children and young people, and more than that, policies to promote the health ‘co-benefits’ of sustainability and climate action could greatly improve health. Surely those messages, if communicated more effectively, could be a strong driver to help us achieve the sort of rapid, meaningful changes we need in order to avoid catastrophic climate change - couldn’t they? In the UK, several thousand health professionals have joined the Climate and Health Council to add their voice to a global climate and health movement which already has strong voices in Australia, Europe and the US, along with several other regions, and they are starting to connect up, for example with the Doha Declaration. Doubt is their product... At the same time, communication with negotiators, the mainstream media and the wider public around what’s known about climate and health clearly hasn’t yet been very effective, and has been compounded by the confusion that biased and inaccurate media such as Fox News and the Murdoch empire seek to create. This is very much like the 'merchants of doubt' phenomenon that emerged among tobacco companies as the evidence of tobacco's health risks came to light. One of my friends recently asked me when he saw this video, “if climate change is really such a big health threat, then why don’t most people know that, and why isn’t it mentioned more in the news?” I’m convinced by the evidence that it is – some of it is collected in our resources section– but I found it hard to answer his question. Have we all, consciously or subconsciously, decided that it’s too depressing so we don’t want to know, do the media decide it’s not worth broadcasting, is it related to the success of fossil fuel companies and their PR and lobbying teams, or is it something else? I don’t have the answers, but I think there are many reasons: for one, picking out long-term trends to ascertain what health impacts are attributable to climate change is no easy task, and – especially when it comes to modelling future health impacts which are often highly dependent on socioeconomic factors too – the science is far from simple. Predictions, of necessity, depend on various assumptions and on multiple interacting factors. As with climate change in general, the real-world effects are highly uncertain: not because scientists think health might be fine in a world four or six degrees hotter, but because it’s very hard to work out exactly how bad the impacts may be. Even the World Bank now explicitly recognises that this is what we’re currently on course towards, that it’ll be far from easy to adapt to, and that such a temperature rise would conflict greatly with its mission to alleviate poverty. The dangers of ignoring Black Swans As George Monbiot pointed out in characteristically optimistic style last year, mainstream global predictions for future food availability in the face of climate change may be wildly off – because they’re based only on average temperatures rather than the extremes. A fatal error if this is true that the extremes – droughts, wildfires and so on – could become the main determinant of global food production, interacting with other changes to affect in ways that, like Taleb's 'Black Swan' events, are almost impossible to predict. If this does turn out to be the case, it’s likely that by far the biggest health impact of climate change will be malnutrition, as argued by Kris Ebi, lead author of the human health section of the last IPCC report. Inadequate food intake not only increases vulnerability to infectious diseases such as malaria, TB, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease, but also kills directly through starvation. Food insecurity, in turn, can force people to migrate just as something more obvious like sea-level rise can, and this can be a driver of civil conflict. Both migration and conflict of course have major physical and health impacts, but their extent and distribution depend on numerous other things; climate is one driver among many. Like any give extreme weather event, it’s hard to attribute indirect effects of climate change such as these to climate change, given how strongly it interacts with other contextual factors. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a causal relationship. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment showed in 2005, our health and wellbeing ultimately depends on ecosystem functioning and stability, at levels from local to global. How ecosystems and in turn health are being – and will be – affected by climate change is unavoidably complex. That makes it hard to communicate and hard to use to change policy, but we cannot allow this to stop effective advocacy and action. The fossil fuel industries and the many dubious institutions and individuals they fund will not wait: with billions made from the sale of coal, oil and gas, they are much better organised and resourced than us at present, and they will use every opportunity to maintain doubt, prolong inaction and ensure that our future isn’t allowed to compromise their sales. In order to extend a sense of the importance of climate action beyond the environmental community and to secure broad and deep consensus on the need for concerted action, health must play a much bigger role in decision-making at all levels. Both impacts and health co-benefits need to feature more centrally in national mitigation and adaptation plans, and in our discussions around climate change more generally. That shift won’t happen on its’ own, and with the Bonn UNFCCC intersessionals coming up in June, it strike me that health should be a priority. Better resourcing and a comprehensive work programme including capacity-building, education and raising public awareness on subjects specific to climate and health would be a tangible and positive way to protect and promote health and to reduce the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable.  Izzy Braithwaite A few weeks ago, I went to an Enough Food IF training day, organised by a number of the big organisations behind the campaign. It aimed to give us the background needed to visit our MPs to talk about two of the main asks – aid and tax – in advance of the Budget and the Finance Bill. The question the IF campaign asks is ‘IF we produce enough food to feed everyone, why do one in 8 people go hungry?’ The crux of the argument is that IF we can change a number of key things about our current system, we can make sure everyone gets enough to eat. I couldn't really argue with that, and I decided I wanted to meet my MP about it - which I did as part of a group on Friday afternoon, and really enjoyed. How is the campaign linked to climate and health? I’ve been interested in global health for several years, focusing more recently on how climate change affects, and will affect, global health, which is how I got involved in Healthy Planet. It seems to me that one of the big impacts climate change is having on people in the poorest countries – and one of the biggest effects it’s likely to have on health in the future - is through food. It makes a lot of sense to me that IF we can build a fairer food system, including through changes in the way tax works for developing countries, that will help reduce the impact of climate-induced crop losses on the health of the poorest. Although the Enough Food IF campaign doesn’t focus explicitly on climate change, there’s a fair amount of evidence that land grabs, food price speculation and short-sighted biofuels policies – all of which the campaign aims to highlight and tackle – act alongside more unstable weather and inadequate social security to push more people into food insecurity. But even if it weren’t for climate change, we have massive injustices around food and access to it; climate change just exacerbates them. You can't really disagree that a world in which almost a billion who don’t have enough to eat while so many others throw away as much as they do, and while so many people are suffering the health effects of obesity, is kind of crazy. Tax and development I didn’t know a lot about the ins and outs of tax policy and how it related to international development before getting involved in the IF campaign, but came away from the training day and my reading online afterwards with a better understanding. I learnt how crucial tax revenue is in enabling developing countries to finance public services, and had no idea that tax avoidance currently costs them to the tune of 3 times as much revenue as they receive in aid each year. I was shocked to learn how Associated British Foods, which produces vast quantities of sugar in Zambia – a country where many people struggle to afford enough to eat – has managed to ensure that it pays less tax in Zambia than the woman in this ActionAid video, a shopkeeper who sells their sugar. Then there was the story about the Rwandan revenue authority, set up with a grant of £24 million from DfID, which now generates that much in tax every 3 weeks. Talk about value for money. That revenue stability enables the Rwandan government to finance essential public services like schools and healthcare, and helps it to ensure that it’s people have enough to eat. If we want aid to be effective and countries to be able to finance aspirations like Universal Health Coverage, tax should be a global health priority, and it was great to have some real examples to illustrate that at the meeting.  The meeting Alison Marshall, who works at Unicef UK and had signed up as a coordinator for my borough on the online lobbying forum, managed to set up a meeting with my MP Jeremy Corbyn for yesterday afternoon, and put everyone who’d expressed an interest in touch with the other interested people in Islington North. About half of those on the email list were able to make it, with quite a range of ages, jobs and backgrounds. Most of us had never met one another before the meeting, so we divided up tasks and subjects in advance and turned up for a chat half an hour before. Unforeseen circumstances meant the office was unavailable that day so we had to relocate, but fortunately an incredible woman called Theresa had offered up the nearby Finsbury Park Community Centre for the meeting. She filled us in on what things are like in the ward, which is one of the most deprived in England, and it was sobering to hear some of the statistics and stories. I'd read a bit about Mr Corbyn’s voting record and past involvement in international development-related work, so I had thought he would probably be happy to support the 0.7% aid goal, but I hadn’t known how he’d respond to the ask on tax transparency, which is a relatively technical one and took more explaining. It relates to the upcoming Finance Bill, and specifically asks that it extends DOTAS (disclosure of tax avoidance schemes) rules to any which impact on developing countries, in order to help them tackle tax avoidance by multinational corporations operating in their countries. The DOTAS regulations help tackle corporate tax avoidance in the UK, and it essentially requires companies to disclose any schemes they use to get out of paying tax. The IF ask (briefing here) is to introduce a similar requirement for UK companies and wealthy individuals to report their use of tax schemes with an impact on developing countries. It also asks that the bill require that when such schemes are identified the UK will use its existing powers under bilateral and multilateral treaties to notify developing countries’ tax authorities, and to assist in the recovery of that tax. Of course, transparency doesn’t in itself prevent tax avoidance, but it does make it much easier to hold companies accountable, and helps to enable developing countries to enforce and improve their laws. And of course UK action is not the whole of the answer – that will include international cooperation, which hopefully the G8 will make progress on, and country-by country reporting amongst other things. But it would be a good step on the road towards a fairer and more effective tax system, and could potentially set a useful precedent for other countries, and the EU, to follow. I quite like a challenge, so I’d kind of hoped we’d have to argue our case a bit more, but in fact he was very much in agreement with both of our asks, and agreed to write to the Chancellor and to lobby other Labour MPs and to raise it after the Budget and the Finance Bill. I suppose I can hardly complain that I have an MP who cares about international development and takes an interest in the details of how we should contribute to it even though most of his time is spent dealing with much more local issues. He told us about some of the problems he'd been trying to fix recently, such as the story of a guy who’d been sleeping on a bus for months who he’d just spent the afternoon trying to get re-housed. I hadn’t really thought there would be many parallels between politics and medicine before the meeting - not least because doctors tend to be trusted by the public whereas many politicians aren’t - but if I'd had to guess his job without knowing, I could easily have guessed a doctor or an overworked social worker. Both are both more of a lifestyle choice than a nine-to-five job, and both doctors and politicians have the opportunity to change peoples’ lives for the better.  Now is when the real test for the campaign begins - making sure there's enough pressure, and enough other MPs on board - to push through specific reforms. Which is where you come in... How can you get involved?

Jonny Elliott The issue of climate-forced migration, and its impacts on human health, is a discourse that is often underplayed when it comes to discussions about climate impacts and adaptation. The ramifications of ignoring it, and consequently failing to put in place appropriate policy frameworks to cope with increased levels of migrants at an international level, will be huge. The health problems associated with climate-related migration also pose a major challenge for existing healthcare systems and the international humanitarian response.

According to International Organisation for Migration and United Nations figures, between 200 million and 1 billion people could be forced to leave their homes between 2010 and 2050 as the effects of climate change worsen, potentially inundating current response strategies. Climate change migration is already happening across the world - right now. Some are migrating because of the direct impacts of natural disasters like floods, droughts and acute water shortages. Whilst indirect impacts such as conflict and increases in food prices can also contribute to people being forced to leave their homes. There is no doubt that forced migration due to climate change will increase the pressure on existing infrastructure and urban services, especially in sanitation, education and social sectors and also consequently increase the risk of conflict over access to scare resources, even amongst migrants. A study released on 28 November, entitled ‘where the rain falls: climate change, food and livelihood security, and migration’ reveals a much more nuanced relationship between projected climate variability and migration, which could provide key insights into likely drivers of migration the coming years. The study, carried out by CARE International and UN University, in 8 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, revealed that in nearly all instances in which rains have become too scarce for farming, people have migrated, but mostly within national borders. At a side event at COP18 on this issue last week, one of the authors, Dr Koko Warner, remarked that "those resilient households use migration to reduce their exposure to climatic variability… In those households, migrants are in their mid-20s, single, move temporarily and send remittances back home. Those resilient households use migration to invest in even more livelihood diversification, education, health and other activities that put them on a positive path to human development." However, there are also much starker consequences for more vulnerable households: 1. Households may migrate in an attempt to manage risk but suffer worse outcomes. They are found in countries with less food security and fewer options to diversify their incomes. They move within their countries seasonally to find work, often as agricultural labourers. 2. The study also described how migration could be an ‘erosive coping strategy’; as a matter of human security, when few other options exist. These households are found in areas where food is even scarcer. They often move during the unpredictable dry season to other rural areas in their regions in search of food or work. 3. Lastly, the study found "households that are trapped and cannot move, and are really at the very margins of existence," according to Warner. These households do not have the capacity to migrate. Health policy making in the context of migration can either been seen as a human rights issue, putting the needs of the individual first, or as a security issue, in terms of its threats to public health (eg. communicable disease control) and social stability. The latter approach relies principally on monitoring, surveillance and screening, and could be argues to be the modern-day cousin of centuries-old quarantine measures, without an individual-focused perspective. The human-rights based approach takes into account nuances and special needs of individuals, as well as the social determinants which may have affected individuals’ health along the migratory pathway. With respect to the UNFCCC process, the response to environmental migration is an area that is particularly underdeveloped. The negotiating text elaborated at Tianjin in 2010 invited Parties to enhance adaptation action under the Adaptation Framework through: [‘m]easures to enhance understanding, coordination and cooperation related to national, regional and international climate change induced displacement, migration and planned relocation, where appropriate’. The Cancun agreement in 2010 took some strides forward and laid out a roadmap for progress with reference to migration, but as yet it hasn’t been implemented, and highlights the need for better and more equitable policy at a global level. As Jane McAdam observes: “Finally—and perhaps most significantly—there seems to be little political appetite for a new international agreement on protection. As one official in Bangladesh pessimistically observed, ‘this is a globe for a rich man’. In “Migration and Climate Change,” a recent publication by UNESCO, Stephen Castles, Associate Director of the International Migration Institute at the University of Oxford suggests that we may need to re-think our strategy. “The doomsday prophesies of environmentalists may have done more to stigmatize refugees and migrants and to support repressive state measures against them, than to raise environmental awareness.” We should be doing more, much more, to raise awareness of this issue, and we must start preparing to cope effectively with the health issues associated with it. Shuo Zhang

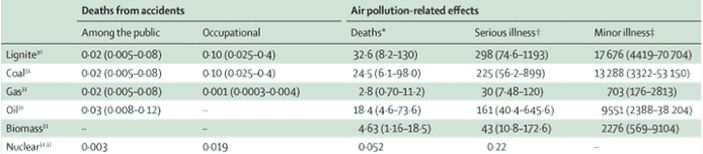

I recently attended Healthy Planet's panel discussion with Professors Hugh Montgomery, Ian Roberts, Anthony Costello and David Satterthwaite during the climate talks. They have all had long and varied careers, but their interests have converged in recent years by a deep motivation to advocate for urgent action on climate change. What really struck me during their presentations, and the subsequent question and answer session, is how far the climate change and health movement has come since the UCL-Lancet Commission in 2008, and also the diversity of perspectives, approaches and forms of engagement on the issues. During these past four years, arguments have been redefined, emphasis redirected, and the movement has taken on board some important new evidence. Past motivations First, a quick history of how the climate change and health movement has gathered momentum. In 2007 Climate and Health Council formed as ‘a meeting of doctors, nurses and other health professionals recognising the urgent need to address climate change to protect health’. In 2008, Anthony Costello led The Lancet commission framed Climate Change as the ‘biggest health threat in the 21st century’ and set forth an interdisciplinary research directive to clarify and quantify the potential magnitude of climate change's direct and indirect health impacts. Impacts such as heat waves, changes in vector disease, air pollution and broader economic and geopolitical instability. The Campaign for Greener Healthcare, now named the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, was set up at the same time to develop a range of projects and programmes which focused on engagement, knowledge sharing, and transformation of the health system. In April of the same year, the NHS Sustainable Development Unit was established to ‘help the NHS fulfil its potential as a leading sustainable and low carbon healthcare service'. They state that they do this by 'developing organisations, people, tools, policy and research which will enable the NHS to promote sustainable development and mitigate climate change'. These strands of global health, NHS sustainability and interest in transformative healthcare came together in 2009 with an organised and coherent health message at The Wave march before COP15 in Copenhagen – that 'what’s good for the climate is good for health'. These strands still very much underlie and motivate the work that is being done, however both the political and economic landscape have changed. There is a new urgency - since the initial Lancet Commission in 2008, new evidence now confirms some previously uncertain climate change impacts - however with the current economic recession, it seems there is less political will and public interest in the topic. Why do we still care? Perspective from the panel came from both personal and professional motivations. Prof Hugh Montgomery articulated the interconnected social, geopolitical and economic impacts on vulnerable populations in the developed and developing world of the indirect impacts of climate change today. This was most keenly illustrated through the impact of global weather on grain harvests, food prices and acting as a contributing factor to the Arab Spring. Resource insecurity further compounds the pressures of future population growth on an already struggling planet. These themes of population, gender empowerment, new technologies, carbon-co benefits, have been consolidated within a development discourse and further, within an intergenerational justice discourse. Prof Anthony Costello presented updated research on the direct health impacts of climate change in terms of disease modelling. It’s not just about future global impacts either. Prof Ian Roberts articulated the difference between demanding action to mitigate against the impacts of carbon on health, and demanding action on the negative health effects of carbon now. Focusing on active travel in particular, he showed the potential benefits of reducing our reliance on the car and embedding active travel in our lifestyles, cities and communities. And not just because it's healthier or lower carbon - but also because it can be more enjoyable. This is applicable across the board: decarbonising our lifestyles re-emphasising meaning over consumption can help us to have healthier bodies and nicer places to live. Prof. Satterthwaite stressed that we mustn't forget that vast populations still live on the edges. They build homes and communities in the high risk peripheries of cities as cities are where today's economic opportunities lie. These incredibly vulnerable settlements need adaptation to the impacts of climate change now, but they are often the least able to vocalise their needs and participate in local governance. So what is needed for the future? Some questions that I feel still need to be answered: should emphasis be on top-down action and policies or bottom-up capacity building? Can city and community level organisations be a new centre of power? How do we make sure that money and support gets to the people who need it most? And how can we ultimately make the most difference? Fundamentally we all need to change what we are doing now, and to make better plans for the future. I feel that healthcare professionals still have a lot to offer - we have a duty of care morally for our patients, and to minimise the impact of our healthcare systems on the planet, since it in turn sustains health. Moreover, healthcare professionals interact with all sectors of society, have a global outreach and from the already existing healthcare partnerships and projects already set up, there is a pre-existing infrastructure there to disseminate information and create change.  Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels. Shuo Zhang The conference of youth has already begun in Durban and the actual Conference of the Parties will be kicking off on Monday. I am both very excited and also a little bit concerned. I am excited because I feel that this year the Medsin delegation has put in so much work on framing our message and in understanding the negotiation process and the various audiences we want to target, that even though I won’t be going to join them, I know that they will all do their best to make the health message be heard.

What I am a little bit concerned by is how the media is going to cover the conference- would very little coverage be preferable to coverage of in fighting and walkouts? How much of the content of the negotiations, as opposed to the dramas will be covered? And something perhaps a little bit more philosophical- is it good that climate change has turned from being news-worthy to being something that is more in the features pages... Most of these worries are a bit excessive, and probably mainly to do with the fact that I won’t be in Durban to throw myself into the work, so instead I will be scouring the media keenly here to keep an eye on how things get translated. However I have been thinking, and realised that sometimes lack of media coverage can perhaps be a good thing. It is easy to get caught up with the negotiations, but what is really important is the long term work on personal, institutional and wider societal change that really matters. Durban is a good spring board to encourage action and enthusiasm and offers a time and place to take stock, however what is really important is for us to let people know about the wonderful work that the already being done. And as healthcare professional we have already been doing a lot, and we have the capacity to do a lot more; we just need to incorporate sustainability into our everyday practice and clinical thinking and make use of the partnerships that are available to us. And as medical students we are in the right place to make these changes, whether through asking climate change and health to be included as part of our curricular, doing projects and SSCs on the subject, and even just asking the consultants who teach us about their own clinical practice, and how they can make it better. So even if we don’t get the media exposure we wanted from the Durban conference, there’s still a lot of very important work to be getting on with! Below are just a few links to the work that the UK health community is already doing well: http://sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/green-nephrology-programme : Spearhead clinical programme that aims to look at how to make renal medicine and dialysis more sustainable http://www.nottenergy.com : A local government and NHS trust partnership that aims to address health inequalities, by working on fuel poverty. http://www.bluegym.org.uk : Community and university project that aims to look at how our coasts can be used for health benefits |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed