Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. It has been quite an experience being out in Warsaw for the climate summit so far, both good and bad - and very tiring! The first week at COP19 was spent mostly finding our feet in Warsaw and at COP19 (the national stadium is a maze!), getting our heads around the negotiations - and just how visible the corporate influence is, with sponsors ranging from coal to car and aviation companies, taking the term greenwashing to an entirely new level (could be a strong case for something similar to Article 5.3 of the WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control here, we think!) We've also had the chance to meet and talk to members of the UK government delegation, from both DECC and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, thanks to our friends over at UKYCC, which was particularly interesting. And we found ourselves in shock - and anger - after the irresponsible moves backwards on climate domestically by both Australia and Japan, especially coming just after the Philippines' lead negotiator Yeb Saño's historic and very moving speech about the devastation wrought by Typhoon Haiyan and his announcement that he was going on hunger strike for the duration of the talks unless there was meaningful progress.  The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action On Monday, we took part in 'People Before Coal', a protest action outside the Ministry of Economy who were - outrageously - hosting a 'Coal and Climate' Summit during the second week of COP19. Perhaps 'coal versus climate' would have been more accurate if you take a look at the World Coal Association's 'Warsaw communique'... Although the fact that the summit was taking place at all is a travesty, the demonstration was a colourful and exciting gathering of people from all over the world; speakers from Poland via the UK to the Philippines and many participants from all over Europe, gathered to highlight the health impacts of coal, on both people and the planet - with these amazing giant inflatable, breathing lungs (!) which were made by #Cough4Coal. There were three scenes in total, showing that the dirty energy future the coal industry's lobbyists are trying to sell us with their Coal Summit is not the clean, healthy future we want. As Christiana Figueres put it at the Summit, "we now know there is an unacceptably high cost (from burning coal) to human and environmental health".  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Along with some of our friends from the International Federation of Medical Students' Associations (IFMSA), we took up the role of young health professionals enthusiastically, with one of our delegation speaking in the gap between two of the scenes about how coal impacts health - both through the air pollution it creates, and through the health impacts of climate change. Some of our photos from the stunt are on the right, with more here; there's also a great blog from 350.org here. One of the best things about COP19 has been the chance to connect up with and talk to other young people from around the world, many of whom have gone to great lengths to fundraise to come and overcome immense obstacles in their fight for climate justice - although our backgrounds and organisations are different, we share a common cause. And it is clear that our governments are currently making nowhere near enough progress towards a binding deal that will keep the planet below dangerous temperatures which would pose a major threat to health. The last few days are likely to focus mainly on Loss and Damage, but - as Yeb Sano has eloquently reminded us - it is essential that we don't lose sight of the ultimate point of the UNFCCC, which is to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate change. At present, the vested interests that rear their heads through 'fossil-friendly' governments like those backing down on climate ambition, are still succeeding in delaying that process for as long as possible.

0 Comments

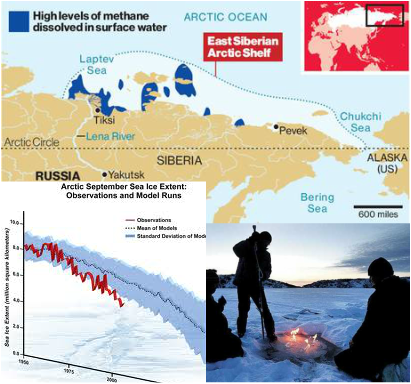

18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.  Land degradation (source: UN/John Isaac) Land degradation (source: UN/John Isaac) Dalvir Kular With conservative estimates forecasting a population of around 9 billion people by 2050, the question of whether the world food system’s production capacity can keep up with increasing demand is a very important one. How it can do so in a world increasingly influenced by climate change is an even tougher question. Imagine if 2013 were the year where we started to take real action on climate change. The year where we changed our course to end malnutrition, for good. I choose to be optimistic. In the global north we have warped our basic need for food into a multi-billion pound industry in which it’s not so much about nutrition but luxury…at least as long as you have the money. In the global south, the losers of our success are driven further into poverty, due to injustices in the political decisions of the global north. The lack of regulation, commodity speculation, inequitable trade policies and climate change combined are helping to send food prices through the roof for the poor. The recent launch of the ‘Enough Food For Everyone IF‘ campaign hammered home the truth that for now, there is enough food available to feed everyone on Earth, but the real problem is how to ensure that people have sufficient access to ensure their food security. Unsustainable energy use and agriculture are fueling a warmer climate, which is resulting in unpredictable and increasingly frequent natural disasters such as floods and droughts. The problems described above – and the increasing shadow of climate change – are directly and indirectly impacting on access to food for the world’s poor; and climate science tells us there’s more to come. Safety nets and speculation According to the United Nations global food reserves are at their lowest levels in nearly 40 years, meaning that there’s a much smaller margin for those already food insecure. If the cost of staples goes up 170%, people either increase their expenditure for the same amount of food, you change your diet to a cheaper and often less nutritious one or you eat less. If you’re poor, ie. when the food required to be secure represents a reasonable proportion of your income, the first option may not be open to you, and there is much less scope to adapt. Rapid urbanisation in the developing world creates the opportunity of greater inequality of livelihoods and income in a higher population density. This give rise to possible future food security issues and a need for safety nets to help city dwellers cope when food prices may be volatile in the future. Helping farmers to adapt to the impacts of climate change can defend food supplies. Laws to prevent speculation have been largely opposed by the big players. Barclays is the biggest UK operator in food commodity markets, making up to an estimated £500m from speculating on food prices in 2010 and 2011. Legislation to limit commodity speculation was backed by the EU in early 2013. Germany’s fourth largest bank, DZ Bank, has announced it would no longer speculate on food prices. Agriculture – especially large-scale, intensive farming of livestock – contributes heavily to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which in turn are a big part of the reason why we’ve been seeing crop failures all around the world, from Africa to the USA to Russia. Agriculture needs to be part of the solution – and with an increase in investment and better policies, sustainable agriculture technologies and practices may be adopted to improve food security and sovereignty for farmers and consumers in the global South, and to reduce emissions and preserve biodiversity. The recent extremely successful UK-based Fish Fight campaign, spearheaded by the food writer Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, is proof that people power – assisted by the internet and social media – can bring real change. It coordinated its supporters to send emails to MEPs in all the official languages of the EU, with more than 120,000 sent within 24 hours in a, successful, effort to ban fish discards. We need similar political momentum to set a more ambitious 40% emissions reduction target for Europe. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which receives nearly 40% of the EU budget must be reformed along the lines advocated by the ‘Enough food for everyone IF’ campaign. It suggests stopping food from becoming fuel for cars, a false economy when it comes to tackling climate change. Certainly we in Europe should pressure our MEPs to lobby for sustainable agriculture in the context of the CAP reform being carried out this year. The idea of a low GHG diet – more domestic, home grown foods, seasonal, local, and including less red meat and dairy – is far from new, but it’s one of the ways that people can make the biggest difference to their carbon footprint. The really good news is that it isn’t only more sustainable, but also often healthier too.  The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) Izzy Braithwaite Originally published at: http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/comment-health-overlooked-in-our-response-to-climate-change/ The protection of human health and wellbeing is a central rationale for the emissions reductions called for in the very first article of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Yet, somehow, the issue is missing from many parts of the UN talks. The growing body of research and evidence in the area over the past couple of decades hasn’t really translated into a broader understanding of how climate change and health are related, beyond a relatively small community of academics and health professionals. Knowledge about the links between climate and health among the public, climate negotiators and environmentalists is often limited and quite superficial. It typically doesn’t stretch far beyond the more direct impacts, such as heatwaves, vector-borne diseases or extreme weather events such as flooding. Indirect effects on health are rarely considered, and both the media and the public tend to frame the impacts of climate change in terms of the risks to ecosystems and species or economic losses; very rarely in terms of its other impacts on people and their health. Perhaps this is part of why climate mitigation and adaptation measures fail to get the levels of both political and financial support they need to tackle climate change and to protect and promote health in the face of it: current levels of adaptation finance, much like current emissions reductions pledges, are grossly inadequate. As a glance at any newspaper or polls about the relative political importance of different topics make clear – most of us are concerned about our own health and the health of those we care about, including that of our children and grandchildren and less visible problems like climate change, which are also delayed in time, often feature far below this on the agenda. Climate change will dramatically affect the health of today’s children and young people, and more than that, policies to promote the health ‘co-benefits’ of sustainability and climate action could greatly improve health. Surely those messages, if communicated more effectively, could be a strong driver to help us achieve the sort of rapid, meaningful changes we need in order to avoid catastrophic climate change - couldn’t they? In the UK, several thousand health professionals have joined the Climate and Health Council to add their voice to a global climate and health movement which already has strong voices in Australia, Europe and the US, along with several other regions, and they are starting to connect up, for example with the Doha Declaration. Doubt is their product... At the same time, communication with negotiators, the mainstream media and the wider public around what’s known about climate and health clearly hasn’t yet been very effective, and has been compounded by the confusion that biased and inaccurate media such as Fox News and the Murdoch empire seek to create. This is very much like the 'merchants of doubt' phenomenon that emerged among tobacco companies as the evidence of tobacco's health risks came to light. One of my friends recently asked me when he saw this video, “if climate change is really such a big health threat, then why don’t most people know that, and why isn’t it mentioned more in the news?” I’m convinced by the evidence that it is – some of it is collected in our resources section– but I found it hard to answer his question. Have we all, consciously or subconsciously, decided that it’s too depressing so we don’t want to know, do the media decide it’s not worth broadcasting, is it related to the success of fossil fuel companies and their PR and lobbying teams, or is it something else? I don’t have the answers, but I think there are many reasons: for one, picking out long-term trends to ascertain what health impacts are attributable to climate change is no easy task, and – especially when it comes to modelling future health impacts which are often highly dependent on socioeconomic factors too – the science is far from simple. Predictions, of necessity, depend on various assumptions and on multiple interacting factors. As with climate change in general, the real-world effects are highly uncertain: not because scientists think health might be fine in a world four or six degrees hotter, but because it’s very hard to work out exactly how bad the impacts may be. Even the World Bank now explicitly recognises that this is what we’re currently on course towards, that it’ll be far from easy to adapt to, and that such a temperature rise would conflict greatly with its mission to alleviate poverty. The dangers of ignoring Black Swans As George Monbiot pointed out in characteristically optimistic style last year, mainstream global predictions for future food availability in the face of climate change may be wildly off – because they’re based only on average temperatures rather than the extremes. A fatal error if this is true that the extremes – droughts, wildfires and so on – could become the main determinant of global food production, interacting with other changes to affect in ways that, like Taleb's 'Black Swan' events, are almost impossible to predict. If this does turn out to be the case, it’s likely that by far the biggest health impact of climate change will be malnutrition, as argued by Kris Ebi, lead author of the human health section of the last IPCC report. Inadequate food intake not only increases vulnerability to infectious diseases such as malaria, TB, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease, but also kills directly through starvation. Food insecurity, in turn, can force people to migrate just as something more obvious like sea-level rise can, and this can be a driver of civil conflict. Both migration and conflict of course have major physical and health impacts, but their extent and distribution depend on numerous other things; climate is one driver among many. Like any give extreme weather event, it’s hard to attribute indirect effects of climate change such as these to climate change, given how strongly it interacts with other contextual factors. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a causal relationship. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment showed in 2005, our health and wellbeing ultimately depends on ecosystem functioning and stability, at levels from local to global. How ecosystems and in turn health are being – and will be – affected by climate change is unavoidably complex. That makes it hard to communicate and hard to use to change policy, but we cannot allow this to stop effective advocacy and action. The fossil fuel industries and the many dubious institutions and individuals they fund will not wait: with billions made from the sale of coal, oil and gas, they are much better organised and resourced than us at present, and they will use every opportunity to maintain doubt, prolong inaction and ensure that our future isn’t allowed to compromise their sales. In order to extend a sense of the importance of climate action beyond the environmental community and to secure broad and deep consensus on the need for concerted action, health must play a much bigger role in decision-making at all levels. Both impacts and health co-benefits need to feature more centrally in national mitigation and adaptation plans, and in our discussions around climate change more generally. That shift won’t happen on its’ own, and with the Bonn UNFCCC intersessionals coming up in June, it strike me that health should be a priority. Better resourcing and a comprehensive work programme including capacity-building, education and raising public awareness on subjects specific to climate and health would be a tangible and positive way to protect and promote health and to reduce the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable. Jonny Elliott, from COP18 We've all been there... if you're anything like me, you probably thought you had climate change sussed when you learnt the difference between your NO2 and your CO2, that simple greenhouse effect diagram they teach you about in GCSE Chemistry, or felt like a genius amongst mere mortals when the Kyoto Protocol was mentioned in conversation. But then you're asked for your views on the Bali Roadmap, or a sample NAPA for a non-annex country, and suddenly you've gone blank and all you can muster is a smile... Welcome to Doha, and to the 18th UN Conference on Climate Change.  Over the next two weeks, I hope to be able to share with you the ins and outs of what can certainly be a tricky process to get your head around: but don’t let that put you off. I am by no means an expert on the whole UNFCCC process - but as Christiana Figueres, the Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC reiterated earlier at an event this week, ‘none of us are, but we all have our niche.’ As a health professional I strongly agree with the UCL-Lancet commission's statement that ‘Climate change could be the biggest global health threat of the 21st century’ . Our health is essentially dependent on stable, functioning ecosystems and a healthy biosphere. This bedrock for global health is under enormous threat from climate change and ecological damage that we are causing. I don’t know about you, but I’ve known about this problem for quite a few years since early secondary school, but have generally felt powerless to act - and at times questioned whether my efforts would really have an effect. However, as I have connected more deeply with other social justice issues, development and public health I've found that the message of climate change and the irrefutable science behind it keeps reappearing. This isn’t just confined to articles we read on PubMed or the Lancet, but is important in our daily lives. It's there in extreme weather events, such as a record-breaking heat wave that I experienced in Washington D.C.; quite possible the flooding that inundated the streets of my hometown Belfast this summer and saw an unlikely hero on a surfboard rescue victims from their homes; the flooding happening across the UK. And it's there in the general trends too. As students, healthcare professionals and people interested in global health, I believe that engaging with this issue really is a case of now or never. We are in a situation in the UK where most are aware of climate change, but all too often turn a blind eye. This is an unavoidable moral responsibility and an issue that will affect ourselves and our children: it's not something in the distant future, it's already happening. And we have to act fast. I urge you over the coming days and weeks to take a second take at what climate change means for you, your family and every single person on this planet. Join me on the journey in Doha where I’ll be creating a bit of a stir on the ground; meeting with negotiators, delivering workshops, training young people from all over the world and leading publicity events such as flashmobs. Forging partnerships and trying to be as accessible as I can will be my allies. Drop me a line, follow me on facebook, or send me a tweet and let’s create a huge wave of change at the UN. It’s our responsibility, so let’s act now! Below: Jonny on the ground in Doha partnering with IFMSA (left) to plan a stunt and with Ex-President of Ireland, Mary Robinson (right) 2/11/2012 Just after Hurricane Sandy, a new report shows that North America has experienced the largest increases in weather-related economic loss eventsRead NowIzzy Braithwaite  As the US starts to pick up the pieces after the recent battering by Hurricane Sandy, many commentators have been discussing its relationship with climate change. Somehow, for the first time since 1984, climate change didn’t come up in any of the three American election debates, whilst Romney's effectively stated his intention to step up where he perceives Obama's failed - and become ''Mr. Oil or Mr. Gas or Mr. Coal'' - or more likely all three. So it comes as no surprise that the NY Mayor Michael Bloomberg has now come out against Romney's position and endorsed Obama on the basis of his environmental track record. Ok, so he may not have achieved much - but he sure stands a better chance of curbing carbon than Romney, who a few months ago got a 30-second applause for using climate change as a punchline. Of course, it is never possible to put single events down to climate change - but this new report released recently by the insurance group Munich Re about long term trends shows that shows that North America has been most affected by weather-related extreme events in recent decades (terms of economic losses - in general, far more lives are lost in poorer regions, due to lower adaptive capacity), and that climate change is part of the reason: ''For the period concerned – 1980 to 2011 – the overall loss burden from weather catastrophes was US $1060bn (in 2011 values).The insured losses amounted to US$ 510bn, and some 30,000 people lost their lives due to weather catastrophes in North America during this time frame.

... Among many other risk insights the study now provides new evidence for the emerging impact of climate change. For thunderstorm-related losses the analysis reveals increasing volatility and a significant long-term upward trend in the normalized figures over the last 40 years. These figures have been adjusted to account for factors such as increasing values, population growth and inflation. A detailed analysis of the time series indicates that the observed changes closely match the pattern of change in meteorological conditions necessary for the formation of large thunderstorm cells. Thus it is quite probable that changing climate conditions are the drivers. The climatic changes detected are in line with the modelled changes due to human-made climate change''. The relationship between climate and hurricane formation is complex: hurricanes aren't caused by climate change as such - the IPCC recently concluded in its SREX report that there is ‘low confidence’ in an observed long-term (40 years or more) increase in tropical cyclone activity – but there is good evidence that such storms are made stronger by its other effects: rising average sea and air temperatures due to climate change mean more moisture in the atmosphere resulting in heavier rain and climate change also drives rising sea levels which result in increased risk of storm surges. For every 1°C that the temperature of the air increases, it can hold 7% more moisture - increasing the potential for flooding. Moreover, Sandy's coincided with an extra-high tide, which increases the threat even further, and flooding has started even before the hurricane has reached. Yet in fact the impacts of natural disasters are some of the easiest health impacts of climate change to quantify. Determining the role of climate change in promoting the spread and (re)emergence of infectious diseases is dramatically more complex. In turn, investigation of how climate change is likely to affect food and water security or - further down the line, economic stability or conflict – is even more fraught with difficulties. The causal chain for such effects is so much more multi-dimensional, depending on so many variables, and the effects less visible - but they could potentially have much bigger effects on health, at least in the long term, than direct impacts of natural disasters. Here we can think of climate change, to some extent as with its effect on hurricanes, as a threat multiplier - and Hurricane Sandy is a call to action. Link to press release about the report: http://www.munichre.com/en/media_relations/press_releases/2012/2012_10_17_press_release.aspx Izzy Braithwaite  It seems I've always liked food. At my 2nd birthday party, I sang 'Happy Cake' instead of 'Happy Birthday.' And I'd agree with George Bernard Shaw when he said, "there is no sincerer love than the love of food." But I'm now a bit more interested in some other questions about food than I was aged two... How could we provide food for 7+ billion people, in a warming world, in a way that doesn't destroy what remains of wild nature or further mess up our atmosphere? It's never possible to attribute a single event to climate change, but there's been a long-term trend of increasing frequency and severity of droughts recently. Last year, East Africa suffered the worst drought in 60 years, putting millions of lives at risk, and tens of thousands are believed to have died before aid arrived. As Amartya Sen pointed out in 1981, political and economic factors are often at least as important in famines as the food shortage itself: in Somalia it was greatly compounded by the activity of the Al-Shabaab rebel militia. Nonetheless, climate change is clearly (excuse the pun) starting to bite. This year droughts are also affecting India and the US, which is experiencing the worst drought in decades. There have been forest fires across Russia, Southern Europe and the USA, and a 25% rise in corn and wheat prices between just June and July. The rapid, record-breaking Arctic ice melt this year, and what it means for us, was described eloquently by George Monbiot: “what we are seeing, here and now, is the transformation of the atmospheric physics of this planet. Three weeks before the likely minimum, the melting of Arctic sea ice has already broken the record set in 2007. The daily rate of loss is now 50% higher than it was that year. The daily sense of loss – of the world we loved and knew – cannot be quantified so easily”. Although these changes seem to be happening even faster than predicted, we still cannot achieve a global emissions agreement. Meanwhile, funding for climate adaptation or biodiversity conservation in developing countries remain only a fraction of global spending on pet food, which totalled $80 billion in 2010. Subsidies, short-sightedness... and the biofuel boom Global agricutural subsidies contribute indirectly both to the conversion of natural habitats, to our increasingly unhealthy diets and to agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Half a trillion dollars is spent annually by developed countries alone subsidising food production and processing, and the US's immense corn subsidies have been linked to the widespread use of unhealthy high-fructose corn syrup, and an increase in corn-fed over grass-fed cattle (producing much more methane). And in the EU, most of the €40 billion currently spent on direct agricultural subsidies goes to larger, wealthier farms, supporting intensive livestock farming and undercutting developing countries. It's not just on land that subsidies are a problem: the World Wildlife Foundation states that fishing subsidies create "a huge incentive to expand fishing fleets and overfish. Today's global fishing fleet is estimated to be up to two and a half times the capacity needed to sustainably fish the oceans. Even as stocks of valuable fish have shrunk, the size of the world's fishing fleets has exploded." Channelling tax money into fishing will only drive stocks nearer to the brink. Propping up a failing industry with subsidies is a bit like trying to get out of financial troubles by printing money. In the long run, it won't work. In view of the 0.8 billion people who go to bed hungry each night and the growing ranks of cars worldwide, current biofuel policies are a terrible idea. When grown on land that was previously forest or, worse still, peatland, they don't even help to combat climate change - the carbon released by clearing peat bog to grow palm oil takes over 1500 years to offset through reduced emissions, and about 75 years for tropical forest. As former World Bank president Ian Goldin put it, biofuel policies are "economically illiterate, environmentally destructive, politically short-sighted and ideologically unsound." Biofuels helped create the 2007-8 global food price spike and - alongside growing demand for beef, soy and palm oil - are a major reason for the conversion of tropical rainforest. The Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that an area of primary forest approximately the size of Greece is lost per year (nearly 15000 hectares per hour). Some land is returned to forest each year, but secondary forest has much lower biodiversity and stores much less carbon than so-called 'old growth' forest. Some scientists believe that - unless we change course soon - most tropical rainforest could be gone within a decade. So how does this relate to my health? It's not all up to governments of course: the food we choose to buy is probably the second most important decision we make in terms of our environmental impact, after flying. It's certainly the biggest one most of us make regularly. Agriculture accounts for 17-32% of the world's carbon footprint, including deforestation, and much of this is associated with livestock. Food miles are often discussed, but cutting back on red meat and dairy is by far the biggest thing most of us could do to reduce our 'foodprint'. A 2006 UN report concluded that cows might be more damaging to the climate than trucks and cars combined - especially with worldwide beef and dairy production expected to double by 2040. Health could also benefit: Professor Ian Roberts argues that if we had to pay more for higher-carbon food, "healthy eating (would) become the easy option." Reducing food waste, currently estimated at around a third of all food produced globally, is a particularly easy win, simultaneously reducing land use, greenhouse gas emissions, landfill and saving money. We can also harness the potential of the internet to make more informed food choices. LandShare's 'FoodPrint' calculator lets you work out the land, water and fossil fuel required for any given diet, whilst 'Hugh's Fish Fight' is an i-Phone app with up-to-date information about sustainable fish. A more global, science-based perspective to our food choices would be useful too: opposing GM isn't going to help prevent billions from going hungry, and organic food, however well-meaning, may just contribute to the continuing expansion of cropland. To close yield gaps and reduce the conversion of pristine habitats, we need to train and support millions of small-scale farmers in developing countries to grow food sustainably and efficiently, and to help protect them from land grabs. "So long as you have food in your mouth, you have solved all questions for the time being" Does that mean we'll have to face food shortages ourselves before we start taking these problems seriously? Admittedly, Kafka was speaking from the perspective of a dog when he wrote this. But the problems with our food system won't solve themselves: and if we don't address, we may find ourselves in a much hotter, hungrier place. So what are the answers? Food - for the poor, and for the future - needs to be much higher on the political agenda. We need to allocate much more funding for research into higher yielding, more climate-resilient crops. Knowledge transfer to and empowerment of farmers in developing countries is also essential, but our consumption choices, especially regarding meat and waste, are at least as important - we need to start thinking of meat as a luxury, to reduce household food waste and to put pressure on food suppliers to do the same. Our food system isn't working - for us or for the planet - and it's up to all of us to fix it. Adapted from Izzy's blog on: http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/the-cambridge-union-society/food-glorious-food_1_b_1831066.html |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed