Izzy Braithwaite A few weeks ago, I went to an Enough Food IF training day, organised by a number of the big organisations behind the campaign. It aimed to give us the background needed to visit our MPs to talk about two of the main asks – aid and tax – in advance of the Budget and the Finance Bill. The question the IF campaign asks is ‘IF we produce enough food to feed everyone, why do one in 8 people go hungry?’ The crux of the argument is that IF we can change a number of key things about our current system, we can make sure everyone gets enough to eat. I couldn't really argue with that, and I decided I wanted to meet my MP about it - which I did as part of a group on Friday afternoon, and really enjoyed. How is the campaign linked to climate and health? I’ve been interested in global health for several years, focusing more recently on how climate change affects, and will affect, global health, which is how I got involved in Healthy Planet. It seems to me that one of the big impacts climate change is having on people in the poorest countries – and one of the biggest effects it’s likely to have on health in the future - is through food. It makes a lot of sense to me that IF we can build a fairer food system, including through changes in the way tax works for developing countries, that will help reduce the impact of climate-induced crop losses on the health of the poorest. Although the Enough Food IF campaign doesn’t focus explicitly on climate change, there’s a fair amount of evidence that land grabs, food price speculation and short-sighted biofuels policies – all of which the campaign aims to highlight and tackle – act alongside more unstable weather and inadequate social security to push more people into food insecurity. But even if it weren’t for climate change, we have massive injustices around food and access to it; climate change just exacerbates them. You can't really disagree that a world in which almost a billion who don’t have enough to eat while so many others throw away as much as they do, and while so many people are suffering the health effects of obesity, is kind of crazy. Tax and development I didn’t know a lot about the ins and outs of tax policy and how it related to international development before getting involved in the IF campaign, but came away from the training day and my reading online afterwards with a better understanding. I learnt how crucial tax revenue is in enabling developing countries to finance public services, and had no idea that tax avoidance currently costs them to the tune of 3 times as much revenue as they receive in aid each year. I was shocked to learn how Associated British Foods, which produces vast quantities of sugar in Zambia – a country where many people struggle to afford enough to eat – has managed to ensure that it pays less tax in Zambia than the woman in this ActionAid video, a shopkeeper who sells their sugar. Then there was the story about the Rwandan revenue authority, set up with a grant of £24 million from DfID, which now generates that much in tax every 3 weeks. Talk about value for money. That revenue stability enables the Rwandan government to finance essential public services like schools and healthcare, and helps it to ensure that it’s people have enough to eat. If we want aid to be effective and countries to be able to finance aspirations like Universal Health Coverage, tax should be a global health priority, and it was great to have some real examples to illustrate that at the meeting.  The meeting Alison Marshall, who works at Unicef UK and had signed up as a coordinator for my borough on the online lobbying forum, managed to set up a meeting with my MP Jeremy Corbyn for yesterday afternoon, and put everyone who’d expressed an interest in touch with the other interested people in Islington North. About half of those on the email list were able to make it, with quite a range of ages, jobs and backgrounds. Most of us had never met one another before the meeting, so we divided up tasks and subjects in advance and turned up for a chat half an hour before. Unforeseen circumstances meant the office was unavailable that day so we had to relocate, but fortunately an incredible woman called Theresa had offered up the nearby Finsbury Park Community Centre for the meeting. She filled us in on what things are like in the ward, which is one of the most deprived in England, and it was sobering to hear some of the statistics and stories. I'd read a bit about Mr Corbyn’s voting record and past involvement in international development-related work, so I had thought he would probably be happy to support the 0.7% aid goal, but I hadn’t known how he’d respond to the ask on tax transparency, which is a relatively technical one and took more explaining. It relates to the upcoming Finance Bill, and specifically asks that it extends DOTAS (disclosure of tax avoidance schemes) rules to any which impact on developing countries, in order to help them tackle tax avoidance by multinational corporations operating in their countries. The DOTAS regulations help tackle corporate tax avoidance in the UK, and it essentially requires companies to disclose any schemes they use to get out of paying tax. The IF ask (briefing here) is to introduce a similar requirement for UK companies and wealthy individuals to report their use of tax schemes with an impact on developing countries. It also asks that the bill require that when such schemes are identified the UK will use its existing powers under bilateral and multilateral treaties to notify developing countries’ tax authorities, and to assist in the recovery of that tax. Of course, transparency doesn’t in itself prevent tax avoidance, but it does make it much easier to hold companies accountable, and helps to enable developing countries to enforce and improve their laws. And of course UK action is not the whole of the answer – that will include international cooperation, which hopefully the G8 will make progress on, and country-by country reporting amongst other things. But it would be a good step on the road towards a fairer and more effective tax system, and could potentially set a useful precedent for other countries, and the EU, to follow. I quite like a challenge, so I’d kind of hoped we’d have to argue our case a bit more, but in fact he was very much in agreement with both of our asks, and agreed to write to the Chancellor and to lobby other Labour MPs and to raise it after the Budget and the Finance Bill. I suppose I can hardly complain that I have an MP who cares about international development and takes an interest in the details of how we should contribute to it even though most of his time is spent dealing with much more local issues. He told us about some of the problems he'd been trying to fix recently, such as the story of a guy who’d been sleeping on a bus for months who he’d just spent the afternoon trying to get re-housed. I hadn’t really thought there would be many parallels between politics and medicine before the meeting - not least because doctors tend to be trusted by the public whereas many politicians aren’t - but if I'd had to guess his job without knowing, I could easily have guessed a doctor or an overworked social worker. Both are both more of a lifestyle choice than a nine-to-five job, and both doctors and politicians have the opportunity to change peoples’ lives for the better.  Now is when the real test for the campaign begins - making sure there's enough pressure, and enough other MPs on board - to push through specific reforms. Which is where you come in... How can you get involved?

1 Comment

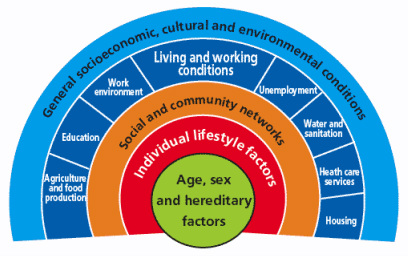

By Shuo Zhang  Dahlgren and Whitehead model (1991) of the determinants of health [6] First published in 'Art of the Possible - the Cambridge Journal of Politics' 2011-02-13 2010 saw a year of spending cuts, riots about public sector reforms and a shift in rhetoric away from “big government” to “big society”. Fundamentally, according to the Coalition Government’s vision, the state needs to move towards leaner, meaner public services and greater freedom and individual choice. This social, institutional and political change has implications for the National Health Service (NHS) in direct and indirect ways, both as a result of the 2010 Health White Paper1 and through the impact on other services that influence wider social determinants of health. Doctors have had a mixed reaction to the new ideas, getting caught up in enticing vocabularysuch as choice and power. However, most have concerns about the risks associated with implementation. The profession faces many challenges in the years to come, not only due to changes in the demography of disease, but also changes in pensions, employment rights and training, technological and scientific innovations, and new emphasis on sustainable practice and preventative medicine. So how has the new Coalition Government approached health and will it meet the challenges for the future? Healthcare is assumed to be a pillar of society and, even in this climate of austerity, the Coalition is keen to be seen to protect the NHS. The 2010 White Paper promises real-term increases in funding, although it also stipulates the need to move towards greater efficiency and cost savings of £20 billion in the next few years. Beyond the economics, the new Health White Paper advocates structural institutional change and a shift in power towards patients and frontline professionals. In addition, public health is to become more integrated with local councils. These proposals have underlined tensions and contradictions that touch upon wider political debates about how the country should navigate this period of hardship.2 One of the most significant proposals is the introduction of the GP-led commissioning service and greater choice for patients when registering with providers. This aims to move control away from managers and towards people who know and use the system the most. This has parallels with existing patient-led support services and health activism that has broadened the health service into a user-provider network, replacing previous patriarchal structures. As an idea, a new directive that empowers patients should be welcomed; it allows them to take their health into their own hands, and could produce a system that is pro-health instead of anti-ill health. In practice, however, the implementation of these proposals may have unintended effects, such as changing the dynamics of the patient-doctor relationship, diverting more time away from patient care due to increases in paperwork and leaving the back door open for potential privatisation. This patient empowerment may also be too far down the line, and only after bad lifestyle choices have already been made, to make much difference to prevention. Furthermore, choice is often just a buzz word for the middle classes, and by creating a system whichpriorities the most vocal needs, hidden inequalities in access and treatment may emerge. A change that perhaps makes more sense is the reconstitution of public health to local authorities. This moves the remit of action for local authorities further up the chain and gives them a greater role in co-ordinating approaches across diverse sectors such as transport and education.3 In effect, it replicates approaches to public health from Victorian England when it formed a central part of town planning. This move will give the medical profession greater powers to address broader social determinants of health, but may also leave it more exposed to criticisms of state ‘nannying’. The government has also failed to consider the continuity of public health in both a community and clinical setting. Public health in clinical practice is vital in providing evidence and improving practice. Moving responsibility for aspects of public health to local councils may create discontinuity and compromise broader goals. The ring-fencing of public health funding under the Coalition signals their intention to continue to address inequalities in access and care; however, this contradicts the cuts to departments in key peripheral areas such as social care and education. To carry on business as usual is not an option. However, the proposed changes were not part of a natural evolution based around principles of adaptation and mitigation, but more of a reactionary event to a system already perturbed. The Coalition’s vision lacks coherence, and there are other ways forward in which power could be better balanced between organizations and individuals. The perspective I have gained from being involved with the climate change and health movement is one of pushing forward change and alternatives to the big picture in a subtle way: changing the way we think about health systems and social structure, changing our behaviour, and seeing savings in efficiency as opportunities rather than cuts.4 It is also a direction which embodies the ethos of ‘prosperity without growth’5 and is careful of the wider political and socio-determinants of health6. The movement realised that it had to re-frame climate change as simply an evolution for the better. For example, infrastructural and efficiency changes will have direct financial savings, with a reduction in emissions as an added bonus. On a personal level, eating less red meat and dairy products, and cycling more will have a primary health benefit as well as positive environmental impacts. In a way, we were trying to change people’s behaviour and thoughts without loading it with values and ideology. Big and, more importantly, sustainable differences can be made if small changes in perspective occur across the board. Ultimately, the danger is that the Coalition Government’s changes are ideologically driven instead of evidence-based. For these changes to be unleashed on an organization that employs 10 per cent of Britain’s workforce without initial trialling is a huge risk. If these structural changes do come into effect it will impact upon fundamental relationships between science, policy and the public. These spheres of influence, which are illustrated by figure 1, extend across individual, group and societal levels. The Coalition should be more aware of these connections. Have they done enough to ensure healthcare will be fit for the future or should we too be protesting for a new way forward? References 1 Department of Health, Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS - Health White Paper 2010, London: The Stationery Office, 2010. 2 British Medical Journal, “More brickbats than bouquets?”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c3977. 3 Anthony Kessel and Andy Haines,“What the white paper might mean for public health”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c6623. 4 Muir Gray and Frances Mortimer, “Transforming Clinical Practice”, Sustainability for health: An evidence base for action, 2 December 2009. http://www.sustainabilityforhealth.org/clinicaltransformation/opinion-pieces/transforming-clinical-practice, accessed 10 January 2011. 5 Tim Jackson 'Prosperity without Growth' (2009) Routledge ISBN-10: 1849713235 http://www.amazon.co.uk/Prosperity-without-Growth-Economics-Finite/dp/1849713235 6 G Dahlgren, M Whitehead 'Policies and strategies to promote equity in health' (1991) World Health Organization. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74737/E89383.pdf |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed