|

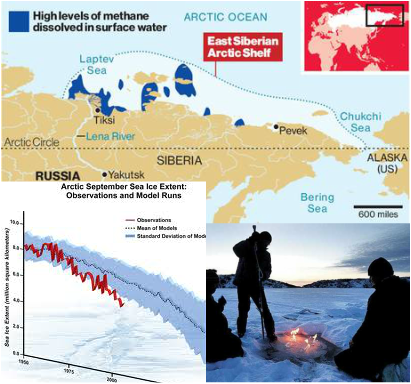

18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.

0 Comments

The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) Izzy Braithwaite Originally published at: http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/comment-health-overlooked-in-our-response-to-climate-change/ The protection of human health and wellbeing is a central rationale for the emissions reductions called for in the very first article of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Yet, somehow, the issue is missing from many parts of the UN talks. The growing body of research and evidence in the area over the past couple of decades hasn’t really translated into a broader understanding of how climate change and health are related, beyond a relatively small community of academics and health professionals. Knowledge about the links between climate and health among the public, climate negotiators and environmentalists is often limited and quite superficial. It typically doesn’t stretch far beyond the more direct impacts, such as heatwaves, vector-borne diseases or extreme weather events such as flooding. Indirect effects on health are rarely considered, and both the media and the public tend to frame the impacts of climate change in terms of the risks to ecosystems and species or economic losses; very rarely in terms of its other impacts on people and their health. Perhaps this is part of why climate mitigation and adaptation measures fail to get the levels of both political and financial support they need to tackle climate change and to protect and promote health in the face of it: current levels of adaptation finance, much like current emissions reductions pledges, are grossly inadequate. As a glance at any newspaper or polls about the relative political importance of different topics make clear – most of us are concerned about our own health and the health of those we care about, including that of our children and grandchildren and less visible problems like climate change, which are also delayed in time, often feature far below this on the agenda. Climate change will dramatically affect the health of today’s children and young people, and more than that, policies to promote the health ‘co-benefits’ of sustainability and climate action could greatly improve health. Surely those messages, if communicated more effectively, could be a strong driver to help us achieve the sort of rapid, meaningful changes we need in order to avoid catastrophic climate change - couldn’t they? In the UK, several thousand health professionals have joined the Climate and Health Council to add their voice to a global climate and health movement which already has strong voices in Australia, Europe and the US, along with several other regions, and they are starting to connect up, for example with the Doha Declaration. Doubt is their product... At the same time, communication with negotiators, the mainstream media and the wider public around what’s known about climate and health clearly hasn’t yet been very effective, and has been compounded by the confusion that biased and inaccurate media such as Fox News and the Murdoch empire seek to create. This is very much like the 'merchants of doubt' phenomenon that emerged among tobacco companies as the evidence of tobacco's health risks came to light. One of my friends recently asked me when he saw this video, “if climate change is really such a big health threat, then why don’t most people know that, and why isn’t it mentioned more in the news?” I’m convinced by the evidence that it is – some of it is collected in our resources section– but I found it hard to answer his question. Have we all, consciously or subconsciously, decided that it’s too depressing so we don’t want to know, do the media decide it’s not worth broadcasting, is it related to the success of fossil fuel companies and their PR and lobbying teams, or is it something else? I don’t have the answers, but I think there are many reasons: for one, picking out long-term trends to ascertain what health impacts are attributable to climate change is no easy task, and – especially when it comes to modelling future health impacts which are often highly dependent on socioeconomic factors too – the science is far from simple. Predictions, of necessity, depend on various assumptions and on multiple interacting factors. As with climate change in general, the real-world effects are highly uncertain: not because scientists think health might be fine in a world four or six degrees hotter, but because it’s very hard to work out exactly how bad the impacts may be. Even the World Bank now explicitly recognises that this is what we’re currently on course towards, that it’ll be far from easy to adapt to, and that such a temperature rise would conflict greatly with its mission to alleviate poverty. The dangers of ignoring Black Swans As George Monbiot pointed out in characteristically optimistic style last year, mainstream global predictions for future food availability in the face of climate change may be wildly off – because they’re based only on average temperatures rather than the extremes. A fatal error if this is true that the extremes – droughts, wildfires and so on – could become the main determinant of global food production, interacting with other changes to affect in ways that, like Taleb's 'Black Swan' events, are almost impossible to predict. If this does turn out to be the case, it’s likely that by far the biggest health impact of climate change will be malnutrition, as argued by Kris Ebi, lead author of the human health section of the last IPCC report. Inadequate food intake not only increases vulnerability to infectious diseases such as malaria, TB, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease, but also kills directly through starvation. Food insecurity, in turn, can force people to migrate just as something more obvious like sea-level rise can, and this can be a driver of civil conflict. Both migration and conflict of course have major physical and health impacts, but their extent and distribution depend on numerous other things; climate is one driver among many. Like any give extreme weather event, it’s hard to attribute indirect effects of climate change such as these to climate change, given how strongly it interacts with other contextual factors. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a causal relationship. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment showed in 2005, our health and wellbeing ultimately depends on ecosystem functioning and stability, at levels from local to global. How ecosystems and in turn health are being – and will be – affected by climate change is unavoidably complex. That makes it hard to communicate and hard to use to change policy, but we cannot allow this to stop effective advocacy and action. The fossil fuel industries and the many dubious institutions and individuals they fund will not wait: with billions made from the sale of coal, oil and gas, they are much better organised and resourced than us at present, and they will use every opportunity to maintain doubt, prolong inaction and ensure that our future isn’t allowed to compromise their sales. In order to extend a sense of the importance of climate action beyond the environmental community and to secure broad and deep consensus on the need for concerted action, health must play a much bigger role in decision-making at all levels. Both impacts and health co-benefits need to feature more centrally in national mitigation and adaptation plans, and in our discussions around climate change more generally. That shift won’t happen on its’ own, and with the Bonn UNFCCC intersessionals coming up in June, it strike me that health should be a priority. Better resourcing and a comprehensive work programme including capacity-building, education and raising public awareness on subjects specific to climate and health would be a tangible and positive way to protect and promote health and to reduce the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable. Jonny Elliott The issue of climate-forced migration, and its impacts on human health, is a discourse that is often underplayed when it comes to discussions about climate impacts and adaptation. The ramifications of ignoring it, and consequently failing to put in place appropriate policy frameworks to cope with increased levels of migrants at an international level, will be huge. The health problems associated with climate-related migration also pose a major challenge for existing healthcare systems and the international humanitarian response.

According to International Organisation for Migration and United Nations figures, between 200 million and 1 billion people could be forced to leave their homes between 2010 and 2050 as the effects of climate change worsen, potentially inundating current response strategies. Climate change migration is already happening across the world - right now. Some are migrating because of the direct impacts of natural disasters like floods, droughts and acute water shortages. Whilst indirect impacts such as conflict and increases in food prices can also contribute to people being forced to leave their homes. There is no doubt that forced migration due to climate change will increase the pressure on existing infrastructure and urban services, especially in sanitation, education and social sectors and also consequently increase the risk of conflict over access to scare resources, even amongst migrants. A study released on 28 November, entitled ‘where the rain falls: climate change, food and livelihood security, and migration’ reveals a much more nuanced relationship between projected climate variability and migration, which could provide key insights into likely drivers of migration the coming years. The study, carried out by CARE International and UN University, in 8 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, revealed that in nearly all instances in which rains have become too scarce for farming, people have migrated, but mostly within national borders. At a side event at COP18 on this issue last week, one of the authors, Dr Koko Warner, remarked that "those resilient households use migration to reduce their exposure to climatic variability… In those households, migrants are in their mid-20s, single, move temporarily and send remittances back home. Those resilient households use migration to invest in even more livelihood diversification, education, health and other activities that put them on a positive path to human development." However, there are also much starker consequences for more vulnerable households: 1. Households may migrate in an attempt to manage risk but suffer worse outcomes. They are found in countries with less food security and fewer options to diversify their incomes. They move within their countries seasonally to find work, often as agricultural labourers. 2. The study also described how migration could be an ‘erosive coping strategy’; as a matter of human security, when few other options exist. These households are found in areas where food is even scarcer. They often move during the unpredictable dry season to other rural areas in their regions in search of food or work. 3. Lastly, the study found "households that are trapped and cannot move, and are really at the very margins of existence," according to Warner. These households do not have the capacity to migrate. Health policy making in the context of migration can either been seen as a human rights issue, putting the needs of the individual first, or as a security issue, in terms of its threats to public health (eg. communicable disease control) and social stability. The latter approach relies principally on monitoring, surveillance and screening, and could be argues to be the modern-day cousin of centuries-old quarantine measures, without an individual-focused perspective. The human-rights based approach takes into account nuances and special needs of individuals, as well as the social determinants which may have affected individuals’ health along the migratory pathway. With respect to the UNFCCC process, the response to environmental migration is an area that is particularly underdeveloped. The negotiating text elaborated at Tianjin in 2010 invited Parties to enhance adaptation action under the Adaptation Framework through: [‘m]easures to enhance understanding, coordination and cooperation related to national, regional and international climate change induced displacement, migration and planned relocation, where appropriate’. The Cancun agreement in 2010 took some strides forward and laid out a roadmap for progress with reference to migration, but as yet it hasn’t been implemented, and highlights the need for better and more equitable policy at a global level. As Jane McAdam observes: “Finally—and perhaps most significantly—there seems to be little political appetite for a new international agreement on protection. As one official in Bangladesh pessimistically observed, ‘this is a globe for a rich man’. In “Migration and Climate Change,” a recent publication by UNESCO, Stephen Castles, Associate Director of the International Migration Institute at the University of Oxford suggests that we may need to re-think our strategy. “The doomsday prophesies of environmentalists may have done more to stigmatize refugees and migrants and to support repressive state measures against them, than to raise environmental awareness.” We should be doing more, much more, to raise awareness of this issue, and we must start preparing to cope effectively with the health issues associated with it. Shuo Zhang

I recently attended Healthy Planet's panel discussion with Professors Hugh Montgomery, Ian Roberts, Anthony Costello and David Satterthwaite during the climate talks. They have all had long and varied careers, but their interests have converged in recent years by a deep motivation to advocate for urgent action on climate change. What really struck me during their presentations, and the subsequent question and answer session, is how far the climate change and health movement has come since the UCL-Lancet Commission in 2008, and also the diversity of perspectives, approaches and forms of engagement on the issues. During these past four years, arguments have been redefined, emphasis redirected, and the movement has taken on board some important new evidence. Past motivations First, a quick history of how the climate change and health movement has gathered momentum. In 2007 Climate and Health Council formed as ‘a meeting of doctors, nurses and other health professionals recognising the urgent need to address climate change to protect health’. In 2008, Anthony Costello led The Lancet commission framed Climate Change as the ‘biggest health threat in the 21st century’ and set forth an interdisciplinary research directive to clarify and quantify the potential magnitude of climate change's direct and indirect health impacts. Impacts such as heat waves, changes in vector disease, air pollution and broader economic and geopolitical instability. The Campaign for Greener Healthcare, now named the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, was set up at the same time to develop a range of projects and programmes which focused on engagement, knowledge sharing, and transformation of the health system. In April of the same year, the NHS Sustainable Development Unit was established to ‘help the NHS fulfil its potential as a leading sustainable and low carbon healthcare service'. They state that they do this by 'developing organisations, people, tools, policy and research which will enable the NHS to promote sustainable development and mitigate climate change'. These strands of global health, NHS sustainability and interest in transformative healthcare came together in 2009 with an organised and coherent health message at The Wave march before COP15 in Copenhagen – that 'what’s good for the climate is good for health'. These strands still very much underlie and motivate the work that is being done, however both the political and economic landscape have changed. There is a new urgency - since the initial Lancet Commission in 2008, new evidence now confirms some previously uncertain climate change impacts - however with the current economic recession, it seems there is less political will and public interest in the topic. Why do we still care? Perspective from the panel came from both personal and professional motivations. Prof Hugh Montgomery articulated the interconnected social, geopolitical and economic impacts on vulnerable populations in the developed and developing world of the indirect impacts of climate change today. This was most keenly illustrated through the impact of global weather on grain harvests, food prices and acting as a contributing factor to the Arab Spring. Resource insecurity further compounds the pressures of future population growth on an already struggling planet. These themes of population, gender empowerment, new technologies, carbon-co benefits, have been consolidated within a development discourse and further, within an intergenerational justice discourse. Prof Anthony Costello presented updated research on the direct health impacts of climate change in terms of disease modelling. It’s not just about future global impacts either. Prof Ian Roberts articulated the difference between demanding action to mitigate against the impacts of carbon on health, and demanding action on the negative health effects of carbon now. Focusing on active travel in particular, he showed the potential benefits of reducing our reliance on the car and embedding active travel in our lifestyles, cities and communities. And not just because it's healthier or lower carbon - but also because it can be more enjoyable. This is applicable across the board: decarbonising our lifestyles re-emphasising meaning over consumption can help us to have healthier bodies and nicer places to live. Prof. Satterthwaite stressed that we mustn't forget that vast populations still live on the edges. They build homes and communities in the high risk peripheries of cities as cities are where today's economic opportunities lie. These incredibly vulnerable settlements need adaptation to the impacts of climate change now, but they are often the least able to vocalise their needs and participate in local governance. So what is needed for the future? Some questions that I feel still need to be answered: should emphasis be on top-down action and policies or bottom-up capacity building? Can city and community level organisations be a new centre of power? How do we make sure that money and support gets to the people who need it most? And how can we ultimately make the most difference? Fundamentally we all need to change what we are doing now, and to make better plans for the future. I feel that healthcare professionals still have a lot to offer - we have a duty of care morally for our patients, and to minimise the impact of our healthcare systems on the planet, since it in turn sustains health. Moreover, healthcare professionals interact with all sectors of society, have a global outreach and from the already existing healthcare partnerships and projects already set up, there is a pre-existing infrastructure there to disseminate information and create change. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed