Photo ©Tony Ray-Jones/RIBA Library Photographs Collection. Photo ©Tony Ray-Jones/RIBA Library Photographs Collection. This blog was originally posted at http://saherhasnain.wordpress.com/2013/01/15/environmental-justice-case-study-pepys-estate-deptford/ on January 15, 2013 by saherhasnain The scenario: A social housing estate in Deptford of Lewisham, London, situated on the banks of the Thames, near a busy transportation route and an industrial site. It was previously the Royal Victoria Dockyard where British warships were constructed. It is characterized by the presence of a number of housing blocks, the completion of which resulted in winning a Civic Trust design award. The area has also been refurbished in recent times. Primary site for background information on the location: ukhousing Problems: The estate has faced a number of problems over time: 1. Physical and social changes accompanied with the newer development, of which the singleaspect blog gives a richer description here 2. Noise pollution from a scrapyard near the center of the estate. The Royal Docks nearby also suffer from noise pollution, but from airplane traffic from the London City Airport. This site is a shining example of citizen science and successful multi-stakeholder collaboration at play. The citizens were assisted by the “Mapping Change for Sustainable Communities” by the London 21 sustainability network and University College London under the UCL-led UrbanBuzz Programme. London Sustainability Exchange, under the Environmental Justice programme provided the second pilot area. The citizens were taught how to use the noise monitoring devices, took their own measurements and made their own map. Further, detailed information on the mobilisation of the residents and the participation of the Mayor and Environment Agency can be found here and here. 3. Air pollution problems also arising from the same scrapyard and proximity to traffic routes, also analysed as part of the citizen science initiative through the London Sustainability Exchange. This time, the citizens took samples to analyse air quality using diffusion tubes for NO2 levels, Eco Badge ozone detection kits and a novel surface wiping method. The results were analysed through the Lancashire University and the results were translated into a series of maps. This contribution influenced the siting of air pollution monitoring units near the estate and it is hoped that the information will help with addressing the environmental quality concerns of the community. Further details can be found with mappingforchange.org.uk The Pepys Estate area can be viewed on google maps below, with reference to the towers, transportation routes, metal and waste recycling plant, Pepys park and the community forum:

0 Comments

Gabriele Messori and Izzy Braithwaite Adapted from a blog post at http://climatesnack.com/2014/01/30/cough-for-coal-at-cop19/#more-1673  Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Neither of us had imagined we’d end up carrying a pair of giant pink lungs in front of the Polish Ministry of Economy on a cold November morning. Why were we there? It’s a long story… We were in Warsaw for COP19, the annual UN climate talks (COP = Conference of the Parties). The aim of the talks is to reach a global deal to tackle climate change in 2015, which will come into force in 2020. We went as part of a delegation of students from Healthy Planet UK, a small, student-led group which seeks to raise awareness about the links between climate and health, and to advocate for UK policy that benefits both health and the environment. As students, researchers and young people, our motivation was the growing body of evidence that climate change poses a major threat to global health, and that sustainable development presents major opportunities for public health. Examples of such climate-health synergies (sometimes called health ‘co-benefits’) can be found across energy, transport, housing and food policy – and quite possibly elsewhere too. Air pollution – bad for health, bad for the climate We know that greenhouse gas emissions affect health indirectly through their contribution to climate change, via changing temperatures and rainfall patterns. Although carbon dioxide has no direct health effect except at high concentrations, it is often, if not invariably, produced alongside other air pollutants. These include substances such as particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen and sulphur oxides, which are emitted both in energy production and motorised transport. Some are greenhouse gases themselves, and all are harmful to our health with myriad effects on our lungs, blood vessels and even cancer risk. The cumulative impact of chronic exposure shortens lives and exacerbates a range of other medical conditions. Around the world, man-made outdoor air pollution accounts for an estimated 2.5 million excess deaths every year. Indoor air pollution (much of it from inefficient cookstoves) accounts for at least as many again, which means that overall air pollution is one of the leading killers globally. Lessons about how politics works… Given the clear evidence that air pollution from burning fossil fuels is so bad for health, combined with the urgency of tackling climate change, you might think governments would be rushing to capitalise on those win-wins. This is where the inflatable lungs come in. Whilst some countries are already taking the kinds of steps that we need, cutting emissions and simultaneously reducing air pollution, over the course of the talks it became fairly clear that some others are working very hard to promote a fossil-fuel dependent future. Almost all of the conference sponsors were fossil-fuel intensive industries. Even more astonishingly, just one day after a summit on climate change and health, organised by the newly-formed Global Climate and Health Alliance, the Polish Ministry of Economy hosted an “International Coal and Climate” summit in parallel with the COP. Feeling that this was outrageous, our team joined many other groups to take part in ‘Cough4Coal’: a public action staged outside the Coal Summit. The stunt involved a series of scenes alternating with speakers from Poland, the Philippines and the UK – one of our team – with the impressive accompaniment of a 7m tall pair of lungs. This was intended to be a visual symbol of the direct health impacts of burning fossil fuels, but also of the less direct health impacts of climate change. Tip of the iceberg

Climate change has been described as “the greatest global health threat of the 21stCentury” by the leading medical journal The Lancet. A 2012 analysis by the DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor arrived at a total of 400,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2010, the greatest burden within this being due to hunger and diarrhoeal disease. However, it is by no means clear that it is accurate to simply extrapolate the future burden due to climate change from the impacts seen so far. These may well be the tip of the iceberg, given that we’ve only seen limited warming relative to what is projected for the coming century. What are the main health impacts of climate change? They range from increased heat exposure, a particular problem among older people and manual labourers, to extreme weather events (which can often affect mental health particularly severely). Changes in the distributions of infectious diseases, and malnutrition and/or starvation due to effects on food production, are equally important. The indirect impacts, such as exacerbation of poverty, migration, and conflict, are both harder to attribute to climate change and significantly harder to forecast. Such impacts are likely to be non-linear and could well be very large indeed – especially with the levels of warming scientists are currently projecting in business-as-usual scenarios. For those interested in finding out more about the health impacts of climate change, we've compiled a summary here. Bridging the gap There may also be pragmatic reasons for framing climate change as a health threat; namely that it connects to people’s own lives and the things they value. In a 2012 study by Teresa Myers and colleagues, a test audience was presented with articles that discussed climate change from a range of different perspectives. Right across audience segments, the articles emphasising the health frame were more likely to elicit strong support for mitigation and adaptation policies than those focusing on the environment or national security. The second working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s fifth assessment report will include a substantial chapter on human health, which could present a useful opportunity for more public communication about climate change using the health frame. It is clear that the stakes are high for health if we continue on our current path. The evidence that action on climate change can benefit public health in all regions is strong – and growing. Emphasising the health implications of climate change can be a powerful way to engage a wider audience in the issue, and everyone with an interest in human health, or just the future of our planet, has a role to play. Not to suggest that you’d need to carry any giant lungs in front of government departments – though by all means get in touch if you’d like to…  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. It has been quite an experience being out in Warsaw for the climate summit so far, both good and bad - and very tiring! The first week at COP19 was spent mostly finding our feet in Warsaw and at COP19 (the national stadium is a maze!), getting our heads around the negotiations - and just how visible the corporate influence is, with sponsors ranging from coal to car and aviation companies, taking the term greenwashing to an entirely new level (could be a strong case for something similar to Article 5.3 of the WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control here, we think!) We've also had the chance to meet and talk to members of the UK government delegation, from both DECC and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, thanks to our friends over at UKYCC, which was particularly interesting. And we found ourselves in shock - and anger - after the irresponsible moves backwards on climate domestically by both Australia and Japan, especially coming just after the Philippines' lead negotiator Yeb Saño's historic and very moving speech about the devastation wrought by Typhoon Haiyan and his announcement that he was going on hunger strike for the duration of the talks unless there was meaningful progress.  The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action On Monday, we took part in 'People Before Coal', a protest action outside the Ministry of Economy who were - outrageously - hosting a 'Coal and Climate' Summit during the second week of COP19. Perhaps 'coal versus climate' would have been more accurate if you take a look at the World Coal Association's 'Warsaw communique'... Although the fact that the summit was taking place at all is a travesty, the demonstration was a colourful and exciting gathering of people from all over the world; speakers from Poland via the UK to the Philippines and many participants from all over Europe, gathered to highlight the health impacts of coal, on both people and the planet - with these amazing giant inflatable, breathing lungs (!) which were made by #Cough4Coal. There were three scenes in total, showing that the dirty energy future the coal industry's lobbyists are trying to sell us with their Coal Summit is not the clean, healthy future we want. As Christiana Figueres put it at the Summit, "we now know there is an unacceptably high cost (from burning coal) to human and environmental health".  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Along with some of our friends from the International Federation of Medical Students' Associations (IFMSA), we took up the role of young health professionals enthusiastically, with one of our delegation speaking in the gap between two of the scenes about how coal impacts health - both through the air pollution it creates, and through the health impacts of climate change. Some of our photos from the stunt are on the right, with more here; there's also a great blog from 350.org here. One of the best things about COP19 has been the chance to connect up with and talk to other young people from around the world, many of whom have gone to great lengths to fundraise to come and overcome immense obstacles in their fight for climate justice - although our backgrounds and organisations are different, we share a common cause. And it is clear that our governments are currently making nowhere near enough progress towards a binding deal that will keep the planet below dangerous temperatures which would pose a major threat to health. The last few days are likely to focus mainly on Loss and Damage, but - as Yeb Sano has eloquently reminded us - it is essential that we don't lose sight of the ultimate point of the UNFCCC, which is to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate change. At present, the vested interests that rear their heads through 'fossil-friendly' governments like those backing down on climate ambition, are still succeeding in delaying that process for as long as possible. By Connor Schwartz  Amartya Sen ponders justice Amartya Sen ponders justice Climate ethics and climate justice are subjects which hide in the background of COPs and treaties, rarely given any limelight of their own. In fact, the most common appeal to climate justice within negotiations are false ones, nations setting out their stall while grasping furiously for some foundations to stand it upon. Because, while the neoliberal hegemony of self-interested actors fails miserably to encompass the breadth of human social relations, it is demonstrably accurate on an international level. Powerful nations may appeal to political theory and forms of justice to back up their positions, but you can bet that their move went outcome first, evidence second, and not the other way around. For example, in the early 2000s while America was resisting becoming party to the Kyoto Protocol, the Bush administration argued furiously that the Annex 1 countries were being unfairly asked to mitigate a crisis which, all things considered, it looked like other countries had a lot more to lose from than themselves. Slowing anthropogenic climate change will cost us a packet and only benefit Tuvalu, how unjust! It did not matter, of course, that this claim is justified only by a philosophy so libertarian that no US president (Nixon included) has ever come close to it. No, much more important to scream “injustice!” and hope nobody really notices that the argument doesn’t stack up. Thus climate ethics has been sullied and debased by negotiators wanting a transcendent justification for their greed. It’s time to put it back at the heart of a global climate regime. Here is just one such attempt. It’s not perfect but I think it reveals a few key things we are looking for from a global climate treaty, and provides the beginnings of a move away from pragmatism and towards justice. Hold tight, here comes the theory. (If you’re not interested in the theory in isolation, jump straight to part two where climate change comes back onto the scene). When we discuss distributive justice of any kind, the first thing to be argued over is what’s called the “metric” – what exactly it is we should be distributing. Let’s narrow our gaze to egalitarianism – that equality is, for some reason, at least partially good – as it is now almost universally accepted across the liberal democracies. There are two traditional camps in the metric debate: resourcists and welfarists. As their names give away, resourcists believe justice includes a focus on equalising the amount of stuff people have, whereas welfarists prefer a focus on the wellbeing or happiness people get from that stuff. It’s the classic means/ends debate. This division has been standing for hundreds of years, splitting radical feminists from their traditional colleagues and communists from conservatives. This impasse however was, I believe, broken in 1979 when Amartya Sen – a heterodox development economist from Bangladesh – gave his Tanner Lecture entitled ‘Equality of What?’. In this lecture Sen dismantled both metrics, each with a simple thought experiment, asking whether what each model was forced to conclude sounded much like justice or not. Number one. Take two agents: one able-bodied and another with a severe disability needing round the clock care. Equalise resources. After covering their care expenditure, the disabled agent has far less resources than the able bodied agent to increase their wellbeing with. Similarly other divides – gender, social position, country of birth, etc. – reach the same conclusion: that a resource egalitarian looks to be saying that justice permits, or even requires, that wellbeing is determined by factors of luck. Ask yourself: does that sound much like justice? Number two. Brian is a plumber living in the city of London and Vikram works as a dabbawalla, distributing Tiffins to the workforce of Mumbai. Brian, from any objective standpoint, enjoys a far higher standard of living than Vikram yet it is certainly conceivable that Vikram is the happier of the two. Empirically, what’s called “hedonic adaptation” shows us that as our income increases so too can our expectations, resulting in no greater happiness. So say Vikram is the happier of the two because he expects less, and we have some spare resources to distribute. We must be persuaded to give the extra to Brian. Justice? To say a poor person has no claim to extra resources because their expectations are lower doesn’t sound much like justice to me. So what does Sen suggest? Justice, he claims, is found in neither resources nor welfare, but some function between the two, some measure of how we can translate resources into welfare. The correct metric for distributive justice is a person’s capabilities or, to be specific, the capability to achieve particular substantive human functionings. Say what? Put simply, what justice demands is equalised are the real and tangible freedoms that humans can possess. It doesn’t matter how much income a person has, if they have no access to healthcare then they are not being served by justice. It does not matter how happy a person is, if they cannot access education then that is a failure of justice.  Martha C. Nussbaum Martha C. Nussbaum Although the language of capabilities was introduced by Sen, it was American theorist Martha C. Nussbaum that developed it into a robust philosophical doctrine. Borrowing from the young Marx, Nussbaum claims that justice provides entitlement to a plurality of values that are both non-aggregable and non-fungible. In other words, we cannot serve justice by simply giving all a certain amount of a certain thing – say, money – and then leaving them to make choices as to how they trade it. Rather, we must concentrate on fulfilling a range of indicators that are distinct and cannot be traded off against each other. Simplistically, one could not for example be compensated for an inadequate life expectancy by being allocated more political rights. This stands explicitly against classical and neoliberal theories of development, relying on GNP to assess the growth of a nation and the wellbeing its peoples. What’s more we do not have to earn these entitlements. They are derived from our entitlement to “the respect and dignity of a life that is fully human”. We possess them, therefore, merely due to our species membership. (Nussbaum also holds that it is likely many other species are similarly entitled to various capabilities, but for now we can just consider our entitlements on account of our being human.) That’s all well and good, but what on earth does it have to do with climate negotiations? Lots, actually. Part two focuses on bringing climate change back into the picture, and putting justice back at the heart of a global climate regime.  The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) Izzy Braithwaite Originally published at: http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/comment-health-overlooked-in-our-response-to-climate-change/ The protection of human health and wellbeing is a central rationale for the emissions reductions called for in the very first article of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Yet, somehow, the issue is missing from many parts of the UN talks. The growing body of research and evidence in the area over the past couple of decades hasn’t really translated into a broader understanding of how climate change and health are related, beyond a relatively small community of academics and health professionals. Knowledge about the links between climate and health among the public, climate negotiators and environmentalists is often limited and quite superficial. It typically doesn’t stretch far beyond the more direct impacts, such as heatwaves, vector-borne diseases or extreme weather events such as flooding. Indirect effects on health are rarely considered, and both the media and the public tend to frame the impacts of climate change in terms of the risks to ecosystems and species or economic losses; very rarely in terms of its other impacts on people and their health. Perhaps this is part of why climate mitigation and adaptation measures fail to get the levels of both political and financial support they need to tackle climate change and to protect and promote health in the face of it: current levels of adaptation finance, much like current emissions reductions pledges, are grossly inadequate. As a glance at any newspaper or polls about the relative political importance of different topics make clear – most of us are concerned about our own health and the health of those we care about, including that of our children and grandchildren and less visible problems like climate change, which are also delayed in time, often feature far below this on the agenda. Climate change will dramatically affect the health of today’s children and young people, and more than that, policies to promote the health ‘co-benefits’ of sustainability and climate action could greatly improve health. Surely those messages, if communicated more effectively, could be a strong driver to help us achieve the sort of rapid, meaningful changes we need in order to avoid catastrophic climate change - couldn’t they? In the UK, several thousand health professionals have joined the Climate and Health Council to add their voice to a global climate and health movement which already has strong voices in Australia, Europe and the US, along with several other regions, and they are starting to connect up, for example with the Doha Declaration. Doubt is their product... At the same time, communication with negotiators, the mainstream media and the wider public around what’s known about climate and health clearly hasn’t yet been very effective, and has been compounded by the confusion that biased and inaccurate media such as Fox News and the Murdoch empire seek to create. This is very much like the 'merchants of doubt' phenomenon that emerged among tobacco companies as the evidence of tobacco's health risks came to light. One of my friends recently asked me when he saw this video, “if climate change is really such a big health threat, then why don’t most people know that, and why isn’t it mentioned more in the news?” I’m convinced by the evidence that it is – some of it is collected in our resources section– but I found it hard to answer his question. Have we all, consciously or subconsciously, decided that it’s too depressing so we don’t want to know, do the media decide it’s not worth broadcasting, is it related to the success of fossil fuel companies and their PR and lobbying teams, or is it something else? I don’t have the answers, but I think there are many reasons: for one, picking out long-term trends to ascertain what health impacts are attributable to climate change is no easy task, and – especially when it comes to modelling future health impacts which are often highly dependent on socioeconomic factors too – the science is far from simple. Predictions, of necessity, depend on various assumptions and on multiple interacting factors. As with climate change in general, the real-world effects are highly uncertain: not because scientists think health might be fine in a world four or six degrees hotter, but because it’s very hard to work out exactly how bad the impacts may be. Even the World Bank now explicitly recognises that this is what we’re currently on course towards, that it’ll be far from easy to adapt to, and that such a temperature rise would conflict greatly with its mission to alleviate poverty. The dangers of ignoring Black Swans As George Monbiot pointed out in characteristically optimistic style last year, mainstream global predictions for future food availability in the face of climate change may be wildly off – because they’re based only on average temperatures rather than the extremes. A fatal error if this is true that the extremes – droughts, wildfires and so on – could become the main determinant of global food production, interacting with other changes to affect in ways that, like Taleb's 'Black Swan' events, are almost impossible to predict. If this does turn out to be the case, it’s likely that by far the biggest health impact of climate change will be malnutrition, as argued by Kris Ebi, lead author of the human health section of the last IPCC report. Inadequate food intake not only increases vulnerability to infectious diseases such as malaria, TB, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease, but also kills directly through starvation. Food insecurity, in turn, can force people to migrate just as something more obvious like sea-level rise can, and this can be a driver of civil conflict. Both migration and conflict of course have major physical and health impacts, but their extent and distribution depend on numerous other things; climate is one driver among many. Like any give extreme weather event, it’s hard to attribute indirect effects of climate change such as these to climate change, given how strongly it interacts with other contextual factors. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a causal relationship. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment showed in 2005, our health and wellbeing ultimately depends on ecosystem functioning and stability, at levels from local to global. How ecosystems and in turn health are being – and will be – affected by climate change is unavoidably complex. That makes it hard to communicate and hard to use to change policy, but we cannot allow this to stop effective advocacy and action. The fossil fuel industries and the many dubious institutions and individuals they fund will not wait: with billions made from the sale of coal, oil and gas, they are much better organised and resourced than us at present, and they will use every opportunity to maintain doubt, prolong inaction and ensure that our future isn’t allowed to compromise their sales. In order to extend a sense of the importance of climate action beyond the environmental community and to secure broad and deep consensus on the need for concerted action, health must play a much bigger role in decision-making at all levels. Both impacts and health co-benefits need to feature more centrally in national mitigation and adaptation plans, and in our discussions around climate change more generally. That shift won’t happen on its’ own, and with the Bonn UNFCCC intersessionals coming up in June, it strike me that health should be a priority. Better resourcing and a comprehensive work programme including capacity-building, education and raising public awareness on subjects specific to climate and health would be a tangible and positive way to protect and promote health and to reduce the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable.  Izzy Braithwaite A few weeks ago, I went to an Enough Food IF training day, organised by a number of the big organisations behind the campaign. It aimed to give us the background needed to visit our MPs to talk about two of the main asks – aid and tax – in advance of the Budget and the Finance Bill. The question the IF campaign asks is ‘IF we produce enough food to feed everyone, why do one in 8 people go hungry?’ The crux of the argument is that IF we can change a number of key things about our current system, we can make sure everyone gets enough to eat. I couldn't really argue with that, and I decided I wanted to meet my MP about it - which I did as part of a group on Friday afternoon, and really enjoyed. How is the campaign linked to climate and health? I’ve been interested in global health for several years, focusing more recently on how climate change affects, and will affect, global health, which is how I got involved in Healthy Planet. It seems to me that one of the big impacts climate change is having on people in the poorest countries – and one of the biggest effects it’s likely to have on health in the future - is through food. It makes a lot of sense to me that IF we can build a fairer food system, including through changes in the way tax works for developing countries, that will help reduce the impact of climate-induced crop losses on the health of the poorest. Although the Enough Food IF campaign doesn’t focus explicitly on climate change, there’s a fair amount of evidence that land grabs, food price speculation and short-sighted biofuels policies – all of which the campaign aims to highlight and tackle – act alongside more unstable weather and inadequate social security to push more people into food insecurity. But even if it weren’t for climate change, we have massive injustices around food and access to it; climate change just exacerbates them. You can't really disagree that a world in which almost a billion who don’t have enough to eat while so many others throw away as much as they do, and while so many people are suffering the health effects of obesity, is kind of crazy. Tax and development I didn’t know a lot about the ins and outs of tax policy and how it related to international development before getting involved in the IF campaign, but came away from the training day and my reading online afterwards with a better understanding. I learnt how crucial tax revenue is in enabling developing countries to finance public services, and had no idea that tax avoidance currently costs them to the tune of 3 times as much revenue as they receive in aid each year. I was shocked to learn how Associated British Foods, which produces vast quantities of sugar in Zambia – a country where many people struggle to afford enough to eat – has managed to ensure that it pays less tax in Zambia than the woman in this ActionAid video, a shopkeeper who sells their sugar. Then there was the story about the Rwandan revenue authority, set up with a grant of £24 million from DfID, which now generates that much in tax every 3 weeks. Talk about value for money. That revenue stability enables the Rwandan government to finance essential public services like schools and healthcare, and helps it to ensure that it’s people have enough to eat. If we want aid to be effective and countries to be able to finance aspirations like Universal Health Coverage, tax should be a global health priority, and it was great to have some real examples to illustrate that at the meeting.  The meeting Alison Marshall, who works at Unicef UK and had signed up as a coordinator for my borough on the online lobbying forum, managed to set up a meeting with my MP Jeremy Corbyn for yesterday afternoon, and put everyone who’d expressed an interest in touch with the other interested people in Islington North. About half of those on the email list were able to make it, with quite a range of ages, jobs and backgrounds. Most of us had never met one another before the meeting, so we divided up tasks and subjects in advance and turned up for a chat half an hour before. Unforeseen circumstances meant the office was unavailable that day so we had to relocate, but fortunately an incredible woman called Theresa had offered up the nearby Finsbury Park Community Centre for the meeting. She filled us in on what things are like in the ward, which is one of the most deprived in England, and it was sobering to hear some of the statistics and stories. I'd read a bit about Mr Corbyn’s voting record and past involvement in international development-related work, so I had thought he would probably be happy to support the 0.7% aid goal, but I hadn’t known how he’d respond to the ask on tax transparency, which is a relatively technical one and took more explaining. It relates to the upcoming Finance Bill, and specifically asks that it extends DOTAS (disclosure of tax avoidance schemes) rules to any which impact on developing countries, in order to help them tackle tax avoidance by multinational corporations operating in their countries. The DOTAS regulations help tackle corporate tax avoidance in the UK, and it essentially requires companies to disclose any schemes they use to get out of paying tax. The IF ask (briefing here) is to introduce a similar requirement for UK companies and wealthy individuals to report their use of tax schemes with an impact on developing countries. It also asks that the bill require that when such schemes are identified the UK will use its existing powers under bilateral and multilateral treaties to notify developing countries’ tax authorities, and to assist in the recovery of that tax. Of course, transparency doesn’t in itself prevent tax avoidance, but it does make it much easier to hold companies accountable, and helps to enable developing countries to enforce and improve their laws. And of course UK action is not the whole of the answer – that will include international cooperation, which hopefully the G8 will make progress on, and country-by country reporting amongst other things. But it would be a good step on the road towards a fairer and more effective tax system, and could potentially set a useful precedent for other countries, and the EU, to follow. I quite like a challenge, so I’d kind of hoped we’d have to argue our case a bit more, but in fact he was very much in agreement with both of our asks, and agreed to write to the Chancellor and to lobby other Labour MPs and to raise it after the Budget and the Finance Bill. I suppose I can hardly complain that I have an MP who cares about international development and takes an interest in the details of how we should contribute to it even though most of his time is spent dealing with much more local issues. He told us about some of the problems he'd been trying to fix recently, such as the story of a guy who’d been sleeping on a bus for months who he’d just spent the afternoon trying to get re-housed. I hadn’t really thought there would be many parallels between politics and medicine before the meeting - not least because doctors tend to be trusted by the public whereas many politicians aren’t - but if I'd had to guess his job without knowing, I could easily have guessed a doctor or an overworked social worker. Both are both more of a lifestyle choice than a nine-to-five job, and both doctors and politicians have the opportunity to change peoples’ lives for the better.  Now is when the real test for the campaign begins - making sure there's enough pressure, and enough other MPs on board - to push through specific reforms. Which is where you come in... How can you get involved?

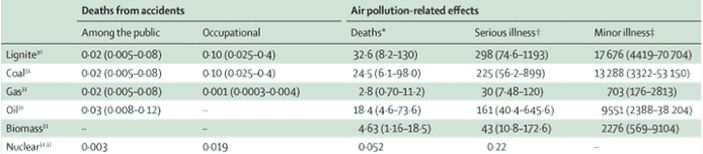

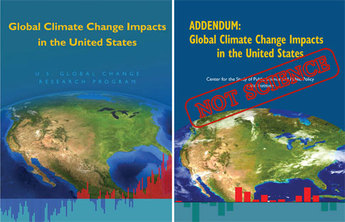

Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels. Izzy Braithwaite  Image courtesy of tcktcktck He may not have achieved much on the climate front in his first term in office, but unlike Mitt Romney, Obama does at least seem to understand the extent of the threat posed by climate change. And - although constrained by the Senate and political will on the ground - he is likely to make more progress on emissions reductions or at least have a better chance of it than Romney. But at the same time, PwC's recent report argues that we are on course for a catastrophic 6C rise by 2100 without urgent measures, and finds that we need deep reductions in carbon intensity of 5.1% per year to 2050 - over six times greater than the 0.8 per cent average annual cuts achieved since 2000 - to avoid dangerous climate change. Such cuts will be a real challenge for even the most committed nations and the US - whether under Romn. And all the while, fossil fuel companies such as ExxonMobil are funding pseudoscience that will help to keep the public in a state of doubt and confusion for some years longer so their profits aren't compromised. The libertarian US Cato Institut based in Washington, DC, recently published its new report, Addendum: Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States - and it is designed to look just like the U.S. government’s official 2009 National Climate Assessment:  This was presented to Congress in 2009 as the federal government's best single evaluation of the science and potential impacts of climate change. Eleven authors of the original government report wrote a recent letter protesting what they called the “deceptive and misleading” Cato report: “The Cato report is in no way an addendum to our 2009 report. It is not an update, explanation, or supplement by the authors of the original report. Rather, it is a completely separate document lacking rigorous scientific analysis and review.” The Union of Concerned Scientists' 2007 report, Smoke, Mirrors, and Hot Air, detailed ExxonMobil’s campaign to use front groups to fund misinformation about climate change. They documented that Michaels was affiliated with no fewer than eleven groups funded by ExxonMobil. Two of the six-member author team on this new Cato report were also highlighted in their 2007 report - Robert Balling was affiliated with no fewer than five “front groups” funded by ExxonMobil. See also DeSmogBlog for other great pieces of investigative journalism on how vested interests have clouded awareness of climate science and impacts - we need to know what we're up against, as they have plenty of money and for a number of the fossil fuel companies it's certainly not matched by their scruples. Izzy Braithwaite  It seems I've always liked food. At my 2nd birthday party, I sang 'Happy Cake' instead of 'Happy Birthday.' And I'd agree with George Bernard Shaw when he said, "there is no sincerer love than the love of food." But I'm now a bit more interested in some other questions about food than I was aged two... How could we provide food for 7+ billion people, in a warming world, in a way that doesn't destroy what remains of wild nature or further mess up our atmosphere? It's never possible to attribute a single event to climate change, but there's been a long-term trend of increasing frequency and severity of droughts recently. Last year, East Africa suffered the worst drought in 60 years, putting millions of lives at risk, and tens of thousands are believed to have died before aid arrived. As Amartya Sen pointed out in 1981, political and economic factors are often at least as important in famines as the food shortage itself: in Somalia it was greatly compounded by the activity of the Al-Shabaab rebel militia. Nonetheless, climate change is clearly (excuse the pun) starting to bite. This year droughts are also affecting India and the US, which is experiencing the worst drought in decades. There have been forest fires across Russia, Southern Europe and the USA, and a 25% rise in corn and wheat prices between just June and July. The rapid, record-breaking Arctic ice melt this year, and what it means for us, was described eloquently by George Monbiot: “what we are seeing, here and now, is the transformation of the atmospheric physics of this planet. Three weeks before the likely minimum, the melting of Arctic sea ice has already broken the record set in 2007. The daily rate of loss is now 50% higher than it was that year. The daily sense of loss – of the world we loved and knew – cannot be quantified so easily”. Although these changes seem to be happening even faster than predicted, we still cannot achieve a global emissions agreement. Meanwhile, funding for climate adaptation or biodiversity conservation in developing countries remain only a fraction of global spending on pet food, which totalled $80 billion in 2010. Subsidies, short-sightedness... and the biofuel boom Global agricutural subsidies contribute indirectly both to the conversion of natural habitats, to our increasingly unhealthy diets and to agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Half a trillion dollars is spent annually by developed countries alone subsidising food production and processing, and the US's immense corn subsidies have been linked to the widespread use of unhealthy high-fructose corn syrup, and an increase in corn-fed over grass-fed cattle (producing much more methane). And in the EU, most of the €40 billion currently spent on direct agricultural subsidies goes to larger, wealthier farms, supporting intensive livestock farming and undercutting developing countries. It's not just on land that subsidies are a problem: the World Wildlife Foundation states that fishing subsidies create "a huge incentive to expand fishing fleets and overfish. Today's global fishing fleet is estimated to be up to two and a half times the capacity needed to sustainably fish the oceans. Even as stocks of valuable fish have shrunk, the size of the world's fishing fleets has exploded." Channelling tax money into fishing will only drive stocks nearer to the brink. Propping up a failing industry with subsidies is a bit like trying to get out of financial troubles by printing money. In the long run, it won't work. In view of the 0.8 billion people who go to bed hungry each night and the growing ranks of cars worldwide, current biofuel policies are a terrible idea. When grown on land that was previously forest or, worse still, peatland, they don't even help to combat climate change - the carbon released by clearing peat bog to grow palm oil takes over 1500 years to offset through reduced emissions, and about 75 years for tropical forest. As former World Bank president Ian Goldin put it, biofuel policies are "economically illiterate, environmentally destructive, politically short-sighted and ideologically unsound." Biofuels helped create the 2007-8 global food price spike and - alongside growing demand for beef, soy and palm oil - are a major reason for the conversion of tropical rainforest. The Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that an area of primary forest approximately the size of Greece is lost per year (nearly 15000 hectares per hour). Some land is returned to forest each year, but secondary forest has much lower biodiversity and stores much less carbon than so-called 'old growth' forest. Some scientists believe that - unless we change course soon - most tropical rainforest could be gone within a decade. So how does this relate to my health? It's not all up to governments of course: the food we choose to buy is probably the second most important decision we make in terms of our environmental impact, after flying. It's certainly the biggest one most of us make regularly. Agriculture accounts for 17-32% of the world's carbon footprint, including deforestation, and much of this is associated with livestock. Food miles are often discussed, but cutting back on red meat and dairy is by far the biggest thing most of us could do to reduce our 'foodprint'. A 2006 UN report concluded that cows might be more damaging to the climate than trucks and cars combined - especially with worldwide beef and dairy production expected to double by 2040. Health could also benefit: Professor Ian Roberts argues that if we had to pay more for higher-carbon food, "healthy eating (would) become the easy option." Reducing food waste, currently estimated at around a third of all food produced globally, is a particularly easy win, simultaneously reducing land use, greenhouse gas emissions, landfill and saving money. We can also harness the potential of the internet to make more informed food choices. LandShare's 'FoodPrint' calculator lets you work out the land, water and fossil fuel required for any given diet, whilst 'Hugh's Fish Fight' is an i-Phone app with up-to-date information about sustainable fish. A more global, science-based perspective to our food choices would be useful too: opposing GM isn't going to help prevent billions from going hungry, and organic food, however well-meaning, may just contribute to the continuing expansion of cropland. To close yield gaps and reduce the conversion of pristine habitats, we need to train and support millions of small-scale farmers in developing countries to grow food sustainably and efficiently, and to help protect them from land grabs. "So long as you have food in your mouth, you have solved all questions for the time being" Does that mean we'll have to face food shortages ourselves before we start taking these problems seriously? Admittedly, Kafka was speaking from the perspective of a dog when he wrote this. But the problems with our food system won't solve themselves: and if we don't address, we may find ourselves in a much hotter, hungrier place. So what are the answers? Food - for the poor, and for the future - needs to be much higher on the political agenda. We need to allocate much more funding for research into higher yielding, more climate-resilient crops. Knowledge transfer to and empowerment of farmers in developing countries is also essential, but our consumption choices, especially regarding meat and waste, are at least as important - we need to start thinking of meat as a luxury, to reduce household food waste and to put pressure on food suppliers to do the same. Our food system isn't working - for us or for the planet - and it's up to all of us to fix it. Adapted from Izzy's blog on: http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/the-cambridge-union-society/food-glorious-food_1_b_1831066.html Jonny Meldrum The UN climate talks were an exhausting, turbulent and yet thrilling time. Reading the lack of coverage in the British press – on the occasions we tried to find out what was happening in the outside world – was always a shock to the complete immersion we experienced in Durban. Everything centred around the negotiations. We read COP17, we talked COP17, we campaigned COP17, we wrote COP17. Christ, we even slept COP17. Now it’s time to document our journey. The Kenyan Youth Climate Caravan (or 6 trucks to be more precise) travelled from Nairobi to Durban over 42 days, carrying 161 climate activists from 18 countries. On the way they performed in local concerts and rallies, engaging and mobilising communities. At their arrival at the Conference of Youth they entered in the room in style to perform to other youth activists from all around the World. It was incredible. Throughout Durban Medsin worked closely with the International Federation of Medical Student Associations (IFMSA), the World Health Organisation and other international health NGOs, to raise awareness of the massive health impacts of climate change and ensuring that the protection of health is an integral part of adaption measures, where countries prepare for the effects of climate change we know are on the way. This year saw the inaugural Climate and Health Summit held in Durban. Opened by the South African Secretary of State for Health, followed by a day of plenaries and panel discussions with experts from the World Health Organisation, Health Care Without Harm and more, the Summit concluded with a Durban Declaration on Climate and Health, signed by hundreds of healthcare professionals, government ministers and summit delegates. This declaration was released in a press conference during which Medsin and the IFMSA staged a demonstration where we took the temperature of the Earth. We felt whilst in South Africa, a country wrought with AIDS, it was of the upmost importance that we highlighted this link. So, to commemorate World AIDS Day, we formed a red human ribbon around the Earth. We gained significant media attention, including coverage on CNN and gave television interviews to broadcasters from around the World. At the end of each day civil society awards the most obstructive country in the talks a ‘fossil’. Countries hate this public shaming and there’s often an official response from government ministers. Here, Canada is awarded 1st place, early on in the conference, not only for refusing to renew their commitments in the Kyoto Protocol, but also entering the week saying they were here to play hard-ball with developing countries whom they were ‘sick of playing the guilt card’. You couldn’t make this stuff up. HOWEVER. The Canadian Youth Delegation, embarrassed and outraged by their country’s behaviour, made it clear throughout the conference that their government were acting on behalf of polluters and not the Canadian people. During the opening statement of their environmental minister at the negotiating plenary, 6 Canadian young people stood up and turned their back on Canada, and were subsequently ‘debadged’ and removed from the conference centre. Many official government delegates from other countries broke into applause and the Canadian minister was visibly shaken. The next day, Abigail Borah, part of the US youth delegation, stood up during the speech of Todd Stern and interrupted the lead US negotiator in an intervention on behalf of the America people: “They cannot speak on behalf of the United States of America … the obstructionist Congress has shackled a just agreement and delayed ambition for far too long.” On the scheduled final day Anjali Appadurai, from Earth in Brackets, delivered an impassioned and powerful speech on behalf of the young constiuency. Afterwards she moved away from the podium and shouted ‘mic check’. This prompted 50 young people spread around the plenary room to stand up and repeat ‘mic check’ in unison. After another mic check she shouted the following: (the italics are the human microphone effect in repetition). Yet again, a significant majority of the government ministers in the room stood and this time gave our intervention a standing ovation, sending a clear message for stronger action. Equity now. You’ve run out of excuses. And we’re running out of time. Get it done. On the last official day of negotiations civil society took an unprecedented stand in solidarity with Africa and Small Island States, representing some of the people most vulnerable to climate change. Hundreds of civil society delegates held a massive protest and went into occupation of the conference centre, right outside the plenary room where ministers were negotiating. Government ministers from the Maldives and a number of African countries joined us and we then escorted them into the negotiation session. The momentum generated was incredible – many negotiators told us that this stand allowed them to push for stronger action inside the hall.  Negotiations continued long into the night from the scheduled end on Friday evening, through Saturday and reaching a conclusion around 5am on Sunday. The major issues surrounded the renewal of the Kyoto Protocol and the roadmap to a future climate deal. Previously the big emerging economies of China, Brazil and India had refused to commit to legally binding targets as part of this future treaty. In the early hours of Sunday morning the South Africa chair of the plenary asked the EU and India to form a huddle to reach an agreement on the legal status of a future deal. This picture was taken metres from the action (- note our very own Chris Huhne centre-right). Brazil suddenly came up with the wording ‘Agreed outcome with legal force’ which both India and EU (and other countries) agreed to, at which point the South Africa chair ran off in much relief to adopt the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. Importantly this means that a future deal, to be agreed by 2015 and implemented in 2020, will be legally binding for all countries. This is good news considering the expectations going into the final days of the conference. However, it’s important to remember there’s still a massive gap in the action required now to safeguard the future survival of millions of people. We’re not done yet. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed