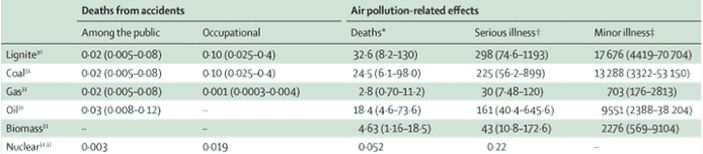

Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels.

0 Comments

|

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed