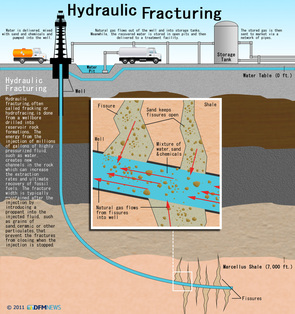

Emily Collins, medical student at Keele University If you’ve seen the news recently, you’ll probably have heard many loud opinions battling to have their say on fracking. Fracking is a process that is unfamiliar to most of us, but which could have big effects on our world, depending on who you listen to. So what is it? And why is it such an important issue? Fracking (hydraulic fracturing) is a feat of engineering aimed to increase the yield of natural gas gleaned from the earth, in order to be used as fuel. As a fossil fuel, formed when marine plankton and ancient plants trapped sunlight energy and carbon over millions of years, natural gas is an unsustainable energy source and burning it produces carbon dioxide. Drills dig deep into the earth, vertically then horizontally, while pumping in water and chemicals at high pressures to open up fissures in the shale rocks way down deep: this frees trapped gases. These are then captured and piped off at the earth’s surface, ready to use as fuel (helpful video: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-23320540.) Having been widely used across the US, the government has recently announced the lifting of a temporary ban of fracking throughout the UK which has sparked controversy and protests, such as those in Balcombe and elsewhere. Why the enthusiasm? Hard to reach oil and gas can be accessed by fracking. It has been estimated that there is as much as 1,300 trillion cubic feet of shale gas underneath the UK – a tenth of which, if extracted, would be the equivalent of 51 years’ gas supply. (1) There are two main possible benefits: first, UK gas prices could be driven down, as they have been in the US. This could be a big boost in the days of our troubled economy, where many families struggle with meeting the rising cost of energy bills – but as this letter to the FT from a senior (republished here) explains, even using very optimistic assumptions only investors in the extraction companies and the Exchequer are likely to benefit, unless gas imports are penalised. At the same time, the cost of solar panels has dropped 80% due to a surge in Chinese production. Is it really just a coincidence that Osborne’s father-in-law is an oil and gas lobbyist?  From an environmental perspective, electricity can be generated from natural gas at half the CO2 emissions of coal (potentially at least) so, compared to coal it could plausibly be a step in the right direction. But there are big question marks on wheter this is true – see below – and is coal really the benchmark we should be using in 2013? Another potential benefit of fracking – especially in the context of today’s record unemployment - is the creation of jobs in Britain. David Cameron claims that as many as 74,000 jobs could be supported by the growth of this industry (1). If true, this would be hard to overlook, although many of them would be temporary. But the job creation argument applies just as strongly to investment in the green economy, as the Green Is Working campaign and this report from the Green Alliance show. Even if realised, the benefits of fracking come with big risks, and could cause lasting damage to our planet and our health. Water usage and chemical contamination Fracking uses huge amounts of water – just one site requires millions of gallons of water. This will compete with water resources in areas which are already prone to and experiencing shortages, areas which are also expected to increase with climate change. Transport of these large volumes of water to and from fracking sites will also have environmental impacts. In addition, there is serious public health concern about the risk of water quality being affected, with a concern that carcinogenic chemicals such as benzene, toluene, xylene etc among many others, used in the water will leak and contaminate groundwater around the site. Earthquakes There are concerns that fracking can cause earth tremors. In 2011, two small earthquakes occurred in Blackpool following exploratory fracking. Several reports have been conducted into the matter and it remains possible that future fracking will lead to some tremors. However, a recent report from the Department for Energy and Climate Change claimed that the risks of structural damage from these tremors remain low, and the process has been given the green light, albeit with stringent regulations.  Climate change The science is telling us that we really need to keep most remaining fossil fuels in the Earth if we want to avoid catastrophic climate change, as highlighted by Bill McKibben's Do The Math talk (coming to the UK this Autumn in a 'Fossil Free' tour coordinated by People and Planet!) In that context, is fracking just a distraction from developing renewable sources of energy? Cameron, like Osborne, says ‘we’re not turning our back on low carbon energy’ - just using fracking to help meet our energy needs – but we could do that with sustainable energy too. Does the move just encourage continued dependence on fossil fuels, ‘one last fix’ before we change? As Friends of the Earth’s Head of Campaigns, Andrew Pendleton, said in reaction to the 2013 Budget: "This is yet another fossil-fuelled Budget.... Our economy desperately needs new ideas, but George Osborne is a 19th century Chancellor, using 20th century tools to fix 21st century problems". Natural gas is mostly methane – which is over 20 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 – and it has been found to leak from fracking sites in quantities much larger than originally thought. Burning fracked natural gas is only a greener alternative to coal burning so long as gas leakages into the environment are kept to a minimum, specifically below 2%. Studies predict, however, that leakages may be significantly higher, with a recent study in Utah finding a leakage rate of 9%. A New Scientist article published yesterday cites that if rates are around 10%, at the top end of estimates for the US, then the escaped gas would increase global warming until the mid 22nd century. The climate is a very complex thing: the same article also notes that side-products of burning coal, sulphur dioxide and black carbon, actually cool the climate to some degree and offset some of the warming created by the production of greenhouse gases – although they also have negative health effects. There’s a lot to consider when it comes to the debate about fracking. What damage to our planet is too much? Will fracking really be the solve-all economic miracle the government is claiming? The debate is open – what do you think?

0 Comments

Shuo Zhang

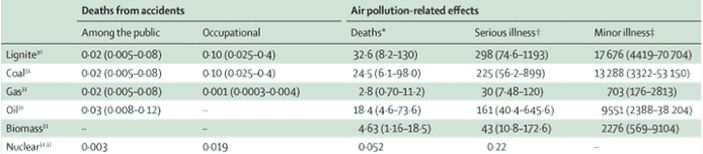

I recently attended Healthy Planet's panel discussion with Professors Hugh Montgomery, Ian Roberts, Anthony Costello and David Satterthwaite during the climate talks. They have all had long and varied careers, but their interests have converged in recent years by a deep motivation to advocate for urgent action on climate change. What really struck me during their presentations, and the subsequent question and answer session, is how far the climate change and health movement has come since the UCL-Lancet Commission in 2008, and also the diversity of perspectives, approaches and forms of engagement on the issues. During these past four years, arguments have been redefined, emphasis redirected, and the movement has taken on board some important new evidence. Past motivations First, a quick history of how the climate change and health movement has gathered momentum. In 2007 Climate and Health Council formed as ‘a meeting of doctors, nurses and other health professionals recognising the urgent need to address climate change to protect health’. In 2008, Anthony Costello led The Lancet commission framed Climate Change as the ‘biggest health threat in the 21st century’ and set forth an interdisciplinary research directive to clarify and quantify the potential magnitude of climate change's direct and indirect health impacts. Impacts such as heat waves, changes in vector disease, air pollution and broader economic and geopolitical instability. The Campaign for Greener Healthcare, now named the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, was set up at the same time to develop a range of projects and programmes which focused on engagement, knowledge sharing, and transformation of the health system. In April of the same year, the NHS Sustainable Development Unit was established to ‘help the NHS fulfil its potential as a leading sustainable and low carbon healthcare service'. They state that they do this by 'developing organisations, people, tools, policy and research which will enable the NHS to promote sustainable development and mitigate climate change'. These strands of global health, NHS sustainability and interest in transformative healthcare came together in 2009 with an organised and coherent health message at The Wave march before COP15 in Copenhagen – that 'what’s good for the climate is good for health'. These strands still very much underlie and motivate the work that is being done, however both the political and economic landscape have changed. There is a new urgency - since the initial Lancet Commission in 2008, new evidence now confirms some previously uncertain climate change impacts - however with the current economic recession, it seems there is less political will and public interest in the topic. Why do we still care? Perspective from the panel came from both personal and professional motivations. Prof Hugh Montgomery articulated the interconnected social, geopolitical and economic impacts on vulnerable populations in the developed and developing world of the indirect impacts of climate change today. This was most keenly illustrated through the impact of global weather on grain harvests, food prices and acting as a contributing factor to the Arab Spring. Resource insecurity further compounds the pressures of future population growth on an already struggling planet. These themes of population, gender empowerment, new technologies, carbon-co benefits, have been consolidated within a development discourse and further, within an intergenerational justice discourse. Prof Anthony Costello presented updated research on the direct health impacts of climate change in terms of disease modelling. It’s not just about future global impacts either. Prof Ian Roberts articulated the difference between demanding action to mitigate against the impacts of carbon on health, and demanding action on the negative health effects of carbon now. Focusing on active travel in particular, he showed the potential benefits of reducing our reliance on the car and embedding active travel in our lifestyles, cities and communities. And not just because it's healthier or lower carbon - but also because it can be more enjoyable. This is applicable across the board: decarbonising our lifestyles re-emphasising meaning over consumption can help us to have healthier bodies and nicer places to live. Prof. Satterthwaite stressed that we mustn't forget that vast populations still live on the edges. They build homes and communities in the high risk peripheries of cities as cities are where today's economic opportunities lie. These incredibly vulnerable settlements need adaptation to the impacts of climate change now, but they are often the least able to vocalise their needs and participate in local governance. So what is needed for the future? Some questions that I feel still need to be answered: should emphasis be on top-down action and policies or bottom-up capacity building? Can city and community level organisations be a new centre of power? How do we make sure that money and support gets to the people who need it most? And how can we ultimately make the most difference? Fundamentally we all need to change what we are doing now, and to make better plans for the future. I feel that healthcare professionals still have a lot to offer - we have a duty of care morally for our patients, and to minimise the impact of our healthcare systems on the planet, since it in turn sustains health. Moreover, healthcare professionals interact with all sectors of society, have a global outreach and from the already existing healthcare partnerships and projects already set up, there is a pre-existing infrastructure there to disseminate information and create change.  Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels. 2/11/2012 Just after Hurricane Sandy, a new report shows that North America has experienced the largest increases in weather-related economic loss eventsRead NowIzzy Braithwaite  As the US starts to pick up the pieces after the recent battering by Hurricane Sandy, many commentators have been discussing its relationship with climate change. Somehow, for the first time since 1984, climate change didn’t come up in any of the three American election debates, whilst Romney's effectively stated his intention to step up where he perceives Obama's failed - and become ''Mr. Oil or Mr. Gas or Mr. Coal'' - or more likely all three. So it comes as no surprise that the NY Mayor Michael Bloomberg has now come out against Romney's position and endorsed Obama on the basis of his environmental track record. Ok, so he may not have achieved much - but he sure stands a better chance of curbing carbon than Romney, who a few months ago got a 30-second applause for using climate change as a punchline. Of course, it is never possible to put single events down to climate change - but this new report released recently by the insurance group Munich Re about long term trends shows that shows that North America has been most affected by weather-related extreme events in recent decades (terms of economic losses - in general, far more lives are lost in poorer regions, due to lower adaptive capacity), and that climate change is part of the reason: ''For the period concerned – 1980 to 2011 – the overall loss burden from weather catastrophes was US $1060bn (in 2011 values).The insured losses amounted to US$ 510bn, and some 30,000 people lost their lives due to weather catastrophes in North America during this time frame.

... Among many other risk insights the study now provides new evidence for the emerging impact of climate change. For thunderstorm-related losses the analysis reveals increasing volatility and a significant long-term upward trend in the normalized figures over the last 40 years. These figures have been adjusted to account for factors such as increasing values, population growth and inflation. A detailed analysis of the time series indicates that the observed changes closely match the pattern of change in meteorological conditions necessary for the formation of large thunderstorm cells. Thus it is quite probable that changing climate conditions are the drivers. The climatic changes detected are in line with the modelled changes due to human-made climate change''. The relationship between climate and hurricane formation is complex: hurricanes aren't caused by climate change as such - the IPCC recently concluded in its SREX report that there is ‘low confidence’ in an observed long-term (40 years or more) increase in tropical cyclone activity – but there is good evidence that such storms are made stronger by its other effects: rising average sea and air temperatures due to climate change mean more moisture in the atmosphere resulting in heavier rain and climate change also drives rising sea levels which result in increased risk of storm surges. For every 1°C that the temperature of the air increases, it can hold 7% more moisture - increasing the potential for flooding. Moreover, Sandy's coincided with an extra-high tide, which increases the threat even further, and flooding has started even before the hurricane has reached. Yet in fact the impacts of natural disasters are some of the easiest health impacts of climate change to quantify. Determining the role of climate change in promoting the spread and (re)emergence of infectious diseases is dramatically more complex. In turn, investigation of how climate change is likely to affect food and water security or - further down the line, economic stability or conflict – is even more fraught with difficulties. The causal chain for such effects is so much more multi-dimensional, depending on so many variables, and the effects less visible - but they could potentially have much bigger effects on health, at least in the long term, than direct impacts of natural disasters. Here we can think of climate change, to some extent as with its effect on hurricanes, as a threat multiplier - and Hurricane Sandy is a call to action. Link to press release about the report: http://www.munichre.com/en/media_relations/press_releases/2012/2012_10_17_press_release.aspx |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed