|

Gabriele Messori and Izzy Braithwaite Adapted from a blog post at http://climatesnack.com/2014/01/30/cough-for-coal-at-cop19/#more-1673  Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Neither of us had imagined we’d end up carrying a pair of giant pink lungs in front of the Polish Ministry of Economy on a cold November morning. Why were we there? It’s a long story… We were in Warsaw for COP19, the annual UN climate talks (COP = Conference of the Parties). The aim of the talks is to reach a global deal to tackle climate change in 2015, which will come into force in 2020. We went as part of a delegation of students from Healthy Planet UK, a small, student-led group which seeks to raise awareness about the links between climate and health, and to advocate for UK policy that benefits both health and the environment. As students, researchers and young people, our motivation was the growing body of evidence that climate change poses a major threat to global health, and that sustainable development presents major opportunities for public health. Examples of such climate-health synergies (sometimes called health ‘co-benefits’) can be found across energy, transport, housing and food policy – and quite possibly elsewhere too. Air pollution – bad for health, bad for the climate We know that greenhouse gas emissions affect health indirectly through their contribution to climate change, via changing temperatures and rainfall patterns. Although carbon dioxide has no direct health effect except at high concentrations, it is often, if not invariably, produced alongside other air pollutants. These include substances such as particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen and sulphur oxides, which are emitted both in energy production and motorised transport. Some are greenhouse gases themselves, and all are harmful to our health with myriad effects on our lungs, blood vessels and even cancer risk. The cumulative impact of chronic exposure shortens lives and exacerbates a range of other medical conditions. Around the world, man-made outdoor air pollution accounts for an estimated 2.5 million excess deaths every year. Indoor air pollution (much of it from inefficient cookstoves) accounts for at least as many again, which means that overall air pollution is one of the leading killers globally. Lessons about how politics works… Given the clear evidence that air pollution from burning fossil fuels is so bad for health, combined with the urgency of tackling climate change, you might think governments would be rushing to capitalise on those win-wins. This is where the inflatable lungs come in. Whilst some countries are already taking the kinds of steps that we need, cutting emissions and simultaneously reducing air pollution, over the course of the talks it became fairly clear that some others are working very hard to promote a fossil-fuel dependent future. Almost all of the conference sponsors were fossil-fuel intensive industries. Even more astonishingly, just one day after a summit on climate change and health, organised by the newly-formed Global Climate and Health Alliance, the Polish Ministry of Economy hosted an “International Coal and Climate” summit in parallel with the COP. Feeling that this was outrageous, our team joined many other groups to take part in ‘Cough4Coal’: a public action staged outside the Coal Summit. The stunt involved a series of scenes alternating with speakers from Poland, the Philippines and the UK – one of our team – with the impressive accompaniment of a 7m tall pair of lungs. This was intended to be a visual symbol of the direct health impacts of burning fossil fuels, but also of the less direct health impacts of climate change. Tip of the iceberg

Climate change has been described as “the greatest global health threat of the 21stCentury” by the leading medical journal The Lancet. A 2012 analysis by the DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor arrived at a total of 400,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2010, the greatest burden within this being due to hunger and diarrhoeal disease. However, it is by no means clear that it is accurate to simply extrapolate the future burden due to climate change from the impacts seen so far. These may well be the tip of the iceberg, given that we’ve only seen limited warming relative to what is projected for the coming century. What are the main health impacts of climate change? They range from increased heat exposure, a particular problem among older people and manual labourers, to extreme weather events (which can often affect mental health particularly severely). Changes in the distributions of infectious diseases, and malnutrition and/or starvation due to effects on food production, are equally important. The indirect impacts, such as exacerbation of poverty, migration, and conflict, are both harder to attribute to climate change and significantly harder to forecast. Such impacts are likely to be non-linear and could well be very large indeed – especially with the levels of warming scientists are currently projecting in business-as-usual scenarios. For those interested in finding out more about the health impacts of climate change, we've compiled a summary here. Bridging the gap There may also be pragmatic reasons for framing climate change as a health threat; namely that it connects to people’s own lives and the things they value. In a 2012 study by Teresa Myers and colleagues, a test audience was presented with articles that discussed climate change from a range of different perspectives. Right across audience segments, the articles emphasising the health frame were more likely to elicit strong support for mitigation and adaptation policies than those focusing on the environment or national security. The second working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s fifth assessment report will include a substantial chapter on human health, which could present a useful opportunity for more public communication about climate change using the health frame. It is clear that the stakes are high for health if we continue on our current path. The evidence that action on climate change can benefit public health in all regions is strong – and growing. Emphasising the health implications of climate change can be a powerful way to engage a wider audience in the issue, and everyone with an interest in human health, or just the future of our planet, has a role to play. Not to suggest that you’d need to carry any giant lungs in front of government departments – though by all means get in touch if you’d like to…

0 Comments

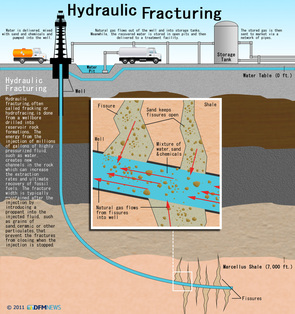

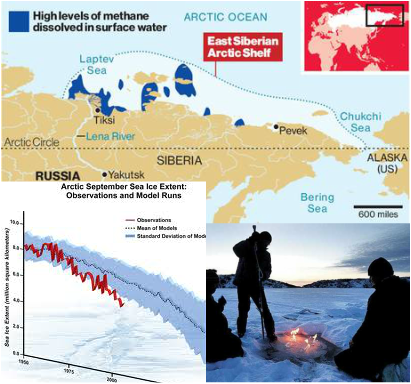

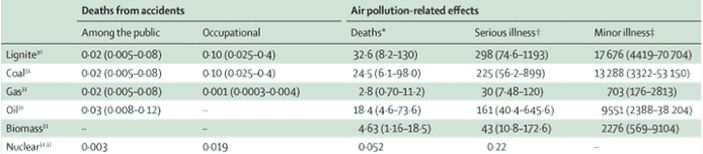

Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. It has been quite an experience being out in Warsaw for the climate summit so far, both good and bad - and very tiring! The first week at COP19 was spent mostly finding our feet in Warsaw and at COP19 (the national stadium is a maze!), getting our heads around the negotiations - and just how visible the corporate influence is, with sponsors ranging from coal to car and aviation companies, taking the term greenwashing to an entirely new level (could be a strong case for something similar to Article 5.3 of the WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control here, we think!) We've also had the chance to meet and talk to members of the UK government delegation, from both DECC and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, thanks to our friends over at UKYCC, which was particularly interesting. And we found ourselves in shock - and anger - after the irresponsible moves backwards on climate domestically by both Australia and Japan, especially coming just after the Philippines' lead negotiator Yeb Saño's historic and very moving speech about the devastation wrought by Typhoon Haiyan and his announcement that he was going on hunger strike for the duration of the talks unless there was meaningful progress.  The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action On Monday, we took part in 'People Before Coal', a protest action outside the Ministry of Economy who were - outrageously - hosting a 'Coal and Climate' Summit during the second week of COP19. Perhaps 'coal versus climate' would have been more accurate if you take a look at the World Coal Association's 'Warsaw communique'... Although the fact that the summit was taking place at all is a travesty, the demonstration was a colourful and exciting gathering of people from all over the world; speakers from Poland via the UK to the Philippines and many participants from all over Europe, gathered to highlight the health impacts of coal, on both people and the planet - with these amazing giant inflatable, breathing lungs (!) which were made by #Cough4Coal. There were three scenes in total, showing that the dirty energy future the coal industry's lobbyists are trying to sell us with their Coal Summit is not the clean, healthy future we want. As Christiana Figueres put it at the Summit, "we now know there is an unacceptably high cost (from burning coal) to human and environmental health".  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Along with some of our friends from the International Federation of Medical Students' Associations (IFMSA), we took up the role of young health professionals enthusiastically, with one of our delegation speaking in the gap between two of the scenes about how coal impacts health - both through the air pollution it creates, and through the health impacts of climate change. Some of our photos from the stunt are on the right, with more here; there's also a great blog from 350.org here. One of the best things about COP19 has been the chance to connect up with and talk to other young people from around the world, many of whom have gone to great lengths to fundraise to come and overcome immense obstacles in their fight for climate justice - although our backgrounds and organisations are different, we share a common cause. And it is clear that our governments are currently making nowhere near enough progress towards a binding deal that will keep the planet below dangerous temperatures which would pose a major threat to health. The last few days are likely to focus mainly on Loss and Damage, but - as Yeb Sano has eloquently reminded us - it is essential that we don't lose sight of the ultimate point of the UNFCCC, which is to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate change. At present, the vested interests that rear their heads through 'fossil-friendly' governments like those backing down on climate ambition, are still succeeding in delaying that process for as long as possible.  Emily Collins, medical student at Keele University If you’ve seen the news recently, you’ll probably have heard many loud opinions battling to have their say on fracking. Fracking is a process that is unfamiliar to most of us, but which could have big effects on our world, depending on who you listen to. So what is it? And why is it such an important issue? Fracking (hydraulic fracturing) is a feat of engineering aimed to increase the yield of natural gas gleaned from the earth, in order to be used as fuel. As a fossil fuel, formed when marine plankton and ancient plants trapped sunlight energy and carbon over millions of years, natural gas is an unsustainable energy source and burning it produces carbon dioxide. Drills dig deep into the earth, vertically then horizontally, while pumping in water and chemicals at high pressures to open up fissures in the shale rocks way down deep: this frees trapped gases. These are then captured and piped off at the earth’s surface, ready to use as fuel (helpful video: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-23320540.) Having been widely used across the US, the government has recently announced the lifting of a temporary ban of fracking throughout the UK which has sparked controversy and protests, such as those in Balcombe and elsewhere. Why the enthusiasm? Hard to reach oil and gas can be accessed by fracking. It has been estimated that there is as much as 1,300 trillion cubic feet of shale gas underneath the UK – a tenth of which, if extracted, would be the equivalent of 51 years’ gas supply. (1) There are two main possible benefits: first, UK gas prices could be driven down, as they have been in the US. This could be a big boost in the days of our troubled economy, where many families struggle with meeting the rising cost of energy bills – but as this letter to the FT from a senior (republished here) explains, even using very optimistic assumptions only investors in the extraction companies and the Exchequer are likely to benefit, unless gas imports are penalised. At the same time, the cost of solar panels has dropped 80% due to a surge in Chinese production. Is it really just a coincidence that Osborne’s father-in-law is an oil and gas lobbyist?  From an environmental perspective, electricity can be generated from natural gas at half the CO2 emissions of coal (potentially at least) so, compared to coal it could plausibly be a step in the right direction. But there are big question marks on wheter this is true – see below – and is coal really the benchmark we should be using in 2013? Another potential benefit of fracking – especially in the context of today’s record unemployment - is the creation of jobs in Britain. David Cameron claims that as many as 74,000 jobs could be supported by the growth of this industry (1). If true, this would be hard to overlook, although many of them would be temporary. But the job creation argument applies just as strongly to investment in the green economy, as the Green Is Working campaign and this report from the Green Alliance show. Even if realised, the benefits of fracking come with big risks, and could cause lasting damage to our planet and our health. Water usage and chemical contamination Fracking uses huge amounts of water – just one site requires millions of gallons of water. This will compete with water resources in areas which are already prone to and experiencing shortages, areas which are also expected to increase with climate change. Transport of these large volumes of water to and from fracking sites will also have environmental impacts. In addition, there is serious public health concern about the risk of water quality being affected, with a concern that carcinogenic chemicals such as benzene, toluene, xylene etc among many others, used in the water will leak and contaminate groundwater around the site. Earthquakes There are concerns that fracking can cause earth tremors. In 2011, two small earthquakes occurred in Blackpool following exploratory fracking. Several reports have been conducted into the matter and it remains possible that future fracking will lead to some tremors. However, a recent report from the Department for Energy and Climate Change claimed that the risks of structural damage from these tremors remain low, and the process has been given the green light, albeit with stringent regulations.  Climate change The science is telling us that we really need to keep most remaining fossil fuels in the Earth if we want to avoid catastrophic climate change, as highlighted by Bill McKibben's Do The Math talk (coming to the UK this Autumn in a 'Fossil Free' tour coordinated by People and Planet!) In that context, is fracking just a distraction from developing renewable sources of energy? Cameron, like Osborne, says ‘we’re not turning our back on low carbon energy’ - just using fracking to help meet our energy needs – but we could do that with sustainable energy too. Does the move just encourage continued dependence on fossil fuels, ‘one last fix’ before we change? As Friends of the Earth’s Head of Campaigns, Andrew Pendleton, said in reaction to the 2013 Budget: "This is yet another fossil-fuelled Budget.... Our economy desperately needs new ideas, but George Osborne is a 19th century Chancellor, using 20th century tools to fix 21st century problems". Natural gas is mostly methane – which is over 20 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 – and it has been found to leak from fracking sites in quantities much larger than originally thought. Burning fracked natural gas is only a greener alternative to coal burning so long as gas leakages into the environment are kept to a minimum, specifically below 2%. Studies predict, however, that leakages may be significantly higher, with a recent study in Utah finding a leakage rate of 9%. A New Scientist article published yesterday cites that if rates are around 10%, at the top end of estimates for the US, then the escaped gas would increase global warming until the mid 22nd century. The climate is a very complex thing: the same article also notes that side-products of burning coal, sulphur dioxide and black carbon, actually cool the climate to some degree and offset some of the warming created by the production of greenhouse gases – although they also have negative health effects. There’s a lot to consider when it comes to the debate about fracking. What damage to our planet is too much? Will fracking really be the solve-all economic miracle the government is claiming? The debate is open – what do you think? 18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.  Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed