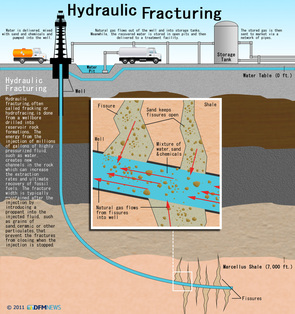

Emily Collins, medical student at Keele University If you’ve seen the news recently, you’ll probably have heard many loud opinions battling to have their say on fracking. Fracking is a process that is unfamiliar to most of us, but which could have big effects on our world, depending on who you listen to. So what is it? And why is it such an important issue? Fracking (hydraulic fracturing) is a feat of engineering aimed to increase the yield of natural gas gleaned from the earth, in order to be used as fuel. As a fossil fuel, formed when marine plankton and ancient plants trapped sunlight energy and carbon over millions of years, natural gas is an unsustainable energy source and burning it produces carbon dioxide. Drills dig deep into the earth, vertically then horizontally, while pumping in water and chemicals at high pressures to open up fissures in the shale rocks way down deep: this frees trapped gases. These are then captured and piped off at the earth’s surface, ready to use as fuel (helpful video: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-23320540.) Having been widely used across the US, the government has recently announced the lifting of a temporary ban of fracking throughout the UK which has sparked controversy and protests, such as those in Balcombe and elsewhere. Why the enthusiasm? Hard to reach oil and gas can be accessed by fracking. It has been estimated that there is as much as 1,300 trillion cubic feet of shale gas underneath the UK – a tenth of which, if extracted, would be the equivalent of 51 years’ gas supply. (1) There are two main possible benefits: first, UK gas prices could be driven down, as they have been in the US. This could be a big boost in the days of our troubled economy, where many families struggle with meeting the rising cost of energy bills – but as this letter to the FT from a senior (republished here) explains, even using very optimistic assumptions only investors in the extraction companies and the Exchequer are likely to benefit, unless gas imports are penalised. At the same time, the cost of solar panels has dropped 80% due to a surge in Chinese production. Is it really just a coincidence that Osborne’s father-in-law is an oil and gas lobbyist?  From an environmental perspective, electricity can be generated from natural gas at half the CO2 emissions of coal (potentially at least) so, compared to coal it could plausibly be a step in the right direction. But there are big question marks on wheter this is true – see below – and is coal really the benchmark we should be using in 2013? Another potential benefit of fracking – especially in the context of today’s record unemployment - is the creation of jobs in Britain. David Cameron claims that as many as 74,000 jobs could be supported by the growth of this industry (1). If true, this would be hard to overlook, although many of them would be temporary. But the job creation argument applies just as strongly to investment in the green economy, as the Green Is Working campaign and this report from the Green Alliance show. Even if realised, the benefits of fracking come with big risks, and could cause lasting damage to our planet and our health. Water usage and chemical contamination Fracking uses huge amounts of water – just one site requires millions of gallons of water. This will compete with water resources in areas which are already prone to and experiencing shortages, areas which are also expected to increase with climate change. Transport of these large volumes of water to and from fracking sites will also have environmental impacts. In addition, there is serious public health concern about the risk of water quality being affected, with a concern that carcinogenic chemicals such as benzene, toluene, xylene etc among many others, used in the water will leak and contaminate groundwater around the site. Earthquakes There are concerns that fracking can cause earth tremors. In 2011, two small earthquakes occurred in Blackpool following exploratory fracking. Several reports have been conducted into the matter and it remains possible that future fracking will lead to some tremors. However, a recent report from the Department for Energy and Climate Change claimed that the risks of structural damage from these tremors remain low, and the process has been given the green light, albeit with stringent regulations.  Climate change The science is telling us that we really need to keep most remaining fossil fuels in the Earth if we want to avoid catastrophic climate change, as highlighted by Bill McKibben's Do The Math talk (coming to the UK this Autumn in a 'Fossil Free' tour coordinated by People and Planet!) In that context, is fracking just a distraction from developing renewable sources of energy? Cameron, like Osborne, says ‘we’re not turning our back on low carbon energy’ - just using fracking to help meet our energy needs – but we could do that with sustainable energy too. Does the move just encourage continued dependence on fossil fuels, ‘one last fix’ before we change? As Friends of the Earth’s Head of Campaigns, Andrew Pendleton, said in reaction to the 2013 Budget: "This is yet another fossil-fuelled Budget.... Our economy desperately needs new ideas, but George Osborne is a 19th century Chancellor, using 20th century tools to fix 21st century problems". Natural gas is mostly methane – which is over 20 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 – and it has been found to leak from fracking sites in quantities much larger than originally thought. Burning fracked natural gas is only a greener alternative to coal burning so long as gas leakages into the environment are kept to a minimum, specifically below 2%. Studies predict, however, that leakages may be significantly higher, with a recent study in Utah finding a leakage rate of 9%. A New Scientist article published yesterday cites that if rates are around 10%, at the top end of estimates for the US, then the escaped gas would increase global warming until the mid 22nd century. The climate is a very complex thing: the same article also notes that side-products of burning coal, sulphur dioxide and black carbon, actually cool the climate to some degree and offset some of the warming created by the production of greenhouse gases – although they also have negative health effects. There’s a lot to consider when it comes to the debate about fracking. What damage to our planet is too much? Will fracking really be the solve-all economic miracle the government is claiming? The debate is open – what do you think?

0 Comments

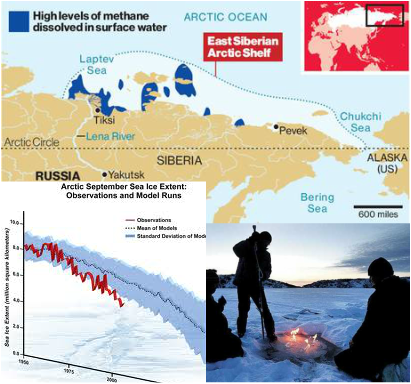

18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.  The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) Izzy Braithwaite Originally published at: http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/comment-health-overlooked-in-our-response-to-climate-change/ The protection of human health and wellbeing is a central rationale for the emissions reductions called for in the very first article of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Yet, somehow, the issue is missing from many parts of the UN talks. The growing body of research and evidence in the area over the past couple of decades hasn’t really translated into a broader understanding of how climate change and health are related, beyond a relatively small community of academics and health professionals. Knowledge about the links between climate and health among the public, climate negotiators and environmentalists is often limited and quite superficial. It typically doesn’t stretch far beyond the more direct impacts, such as heatwaves, vector-borne diseases or extreme weather events such as flooding. Indirect effects on health are rarely considered, and both the media and the public tend to frame the impacts of climate change in terms of the risks to ecosystems and species or economic losses; very rarely in terms of its other impacts on people and their health. Perhaps this is part of why climate mitigation and adaptation measures fail to get the levels of both political and financial support they need to tackle climate change and to protect and promote health in the face of it: current levels of adaptation finance, much like current emissions reductions pledges, are grossly inadequate. As a glance at any newspaper or polls about the relative political importance of different topics make clear – most of us are concerned about our own health and the health of those we care about, including that of our children and grandchildren and less visible problems like climate change, which are also delayed in time, often feature far below this on the agenda. Climate change will dramatically affect the health of today’s children and young people, and more than that, policies to promote the health ‘co-benefits’ of sustainability and climate action could greatly improve health. Surely those messages, if communicated more effectively, could be a strong driver to help us achieve the sort of rapid, meaningful changes we need in order to avoid catastrophic climate change - couldn’t they? In the UK, several thousand health professionals have joined the Climate and Health Council to add their voice to a global climate and health movement which already has strong voices in Australia, Europe and the US, along with several other regions, and they are starting to connect up, for example with the Doha Declaration. Doubt is their product... At the same time, communication with negotiators, the mainstream media and the wider public around what’s known about climate and health clearly hasn’t yet been very effective, and has been compounded by the confusion that biased and inaccurate media such as Fox News and the Murdoch empire seek to create. This is very much like the 'merchants of doubt' phenomenon that emerged among tobacco companies as the evidence of tobacco's health risks came to light. One of my friends recently asked me when he saw this video, “if climate change is really such a big health threat, then why don’t most people know that, and why isn’t it mentioned more in the news?” I’m convinced by the evidence that it is – some of it is collected in our resources section– but I found it hard to answer his question. Have we all, consciously or subconsciously, decided that it’s too depressing so we don’t want to know, do the media decide it’s not worth broadcasting, is it related to the success of fossil fuel companies and their PR and lobbying teams, or is it something else? I don’t have the answers, but I think there are many reasons: for one, picking out long-term trends to ascertain what health impacts are attributable to climate change is no easy task, and – especially when it comes to modelling future health impacts which are often highly dependent on socioeconomic factors too – the science is far from simple. Predictions, of necessity, depend on various assumptions and on multiple interacting factors. As with climate change in general, the real-world effects are highly uncertain: not because scientists think health might be fine in a world four or six degrees hotter, but because it’s very hard to work out exactly how bad the impacts may be. Even the World Bank now explicitly recognises that this is what we’re currently on course towards, that it’ll be far from easy to adapt to, and that such a temperature rise would conflict greatly with its mission to alleviate poverty. The dangers of ignoring Black Swans As George Monbiot pointed out in characteristically optimistic style last year, mainstream global predictions for future food availability in the face of climate change may be wildly off – because they’re based only on average temperatures rather than the extremes. A fatal error if this is true that the extremes – droughts, wildfires and so on – could become the main determinant of global food production, interacting with other changes to affect in ways that, like Taleb's 'Black Swan' events, are almost impossible to predict. If this does turn out to be the case, it’s likely that by far the biggest health impact of climate change will be malnutrition, as argued by Kris Ebi, lead author of the human health section of the last IPCC report. Inadequate food intake not only increases vulnerability to infectious diseases such as malaria, TB, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease, but also kills directly through starvation. Food insecurity, in turn, can force people to migrate just as something more obvious like sea-level rise can, and this can be a driver of civil conflict. Both migration and conflict of course have major physical and health impacts, but their extent and distribution depend on numerous other things; climate is one driver among many. Like any give extreme weather event, it’s hard to attribute indirect effects of climate change such as these to climate change, given how strongly it interacts with other contextual factors. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a causal relationship. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment showed in 2005, our health and wellbeing ultimately depends on ecosystem functioning and stability, at levels from local to global. How ecosystems and in turn health are being – and will be – affected by climate change is unavoidably complex. That makes it hard to communicate and hard to use to change policy, but we cannot allow this to stop effective advocacy and action. The fossil fuel industries and the many dubious institutions and individuals they fund will not wait: with billions made from the sale of coal, oil and gas, they are much better organised and resourced than us at present, and they will use every opportunity to maintain doubt, prolong inaction and ensure that our future isn’t allowed to compromise their sales. In order to extend a sense of the importance of climate action beyond the environmental community and to secure broad and deep consensus on the need for concerted action, health must play a much bigger role in decision-making at all levels. Both impacts and health co-benefits need to feature more centrally in national mitigation and adaptation plans, and in our discussions around climate change more generally. That shift won’t happen on its’ own, and with the Bonn UNFCCC intersessionals coming up in June, it strike me that health should be a priority. Better resourcing and a comprehensive work programme including capacity-building, education and raising public awareness on subjects specific to climate and health would be a tangible and positive way to protect and promote health and to reduce the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable. Shuo Zhang

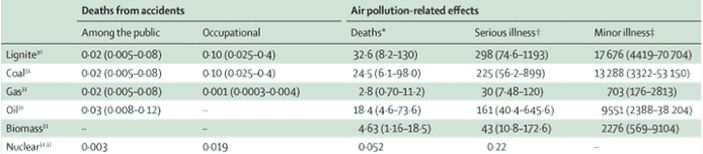

I recently attended Healthy Planet's panel discussion with Professors Hugh Montgomery, Ian Roberts, Anthony Costello and David Satterthwaite during the climate talks. They have all had long and varied careers, but their interests have converged in recent years by a deep motivation to advocate for urgent action on climate change. What really struck me during their presentations, and the subsequent question and answer session, is how far the climate change and health movement has come since the UCL-Lancet Commission in 2008, and also the diversity of perspectives, approaches and forms of engagement on the issues. During these past four years, arguments have been redefined, emphasis redirected, and the movement has taken on board some important new evidence. Past motivations First, a quick history of how the climate change and health movement has gathered momentum. In 2007 Climate and Health Council formed as ‘a meeting of doctors, nurses and other health professionals recognising the urgent need to address climate change to protect health’. In 2008, Anthony Costello led The Lancet commission framed Climate Change as the ‘biggest health threat in the 21st century’ and set forth an interdisciplinary research directive to clarify and quantify the potential magnitude of climate change's direct and indirect health impacts. Impacts such as heat waves, changes in vector disease, air pollution and broader economic and geopolitical instability. The Campaign for Greener Healthcare, now named the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, was set up at the same time to develop a range of projects and programmes which focused on engagement, knowledge sharing, and transformation of the health system. In April of the same year, the NHS Sustainable Development Unit was established to ‘help the NHS fulfil its potential as a leading sustainable and low carbon healthcare service'. They state that they do this by 'developing organisations, people, tools, policy and research which will enable the NHS to promote sustainable development and mitigate climate change'. These strands of global health, NHS sustainability and interest in transformative healthcare came together in 2009 with an organised and coherent health message at The Wave march before COP15 in Copenhagen – that 'what’s good for the climate is good for health'. These strands still very much underlie and motivate the work that is being done, however both the political and economic landscape have changed. There is a new urgency - since the initial Lancet Commission in 2008, new evidence now confirms some previously uncertain climate change impacts - however with the current economic recession, it seems there is less political will and public interest in the topic. Why do we still care? Perspective from the panel came from both personal and professional motivations. Prof Hugh Montgomery articulated the interconnected social, geopolitical and economic impacts on vulnerable populations in the developed and developing world of the indirect impacts of climate change today. This was most keenly illustrated through the impact of global weather on grain harvests, food prices and acting as a contributing factor to the Arab Spring. Resource insecurity further compounds the pressures of future population growth on an already struggling planet. These themes of population, gender empowerment, new technologies, carbon-co benefits, have been consolidated within a development discourse and further, within an intergenerational justice discourse. Prof Anthony Costello presented updated research on the direct health impacts of climate change in terms of disease modelling. It’s not just about future global impacts either. Prof Ian Roberts articulated the difference between demanding action to mitigate against the impacts of carbon on health, and demanding action on the negative health effects of carbon now. Focusing on active travel in particular, he showed the potential benefits of reducing our reliance on the car and embedding active travel in our lifestyles, cities and communities. And not just because it's healthier or lower carbon - but also because it can be more enjoyable. This is applicable across the board: decarbonising our lifestyles re-emphasising meaning over consumption can help us to have healthier bodies and nicer places to live. Prof. Satterthwaite stressed that we mustn't forget that vast populations still live on the edges. They build homes and communities in the high risk peripheries of cities as cities are where today's economic opportunities lie. These incredibly vulnerable settlements need adaptation to the impacts of climate change now, but they are often the least able to vocalise their needs and participate in local governance. So what is needed for the future? Some questions that I feel still need to be answered: should emphasis be on top-down action and policies or bottom-up capacity building? Can city and community level organisations be a new centre of power? How do we make sure that money and support gets to the people who need it most? And how can we ultimately make the most difference? Fundamentally we all need to change what we are doing now, and to make better plans for the future. I feel that healthcare professionals still have a lot to offer - we have a duty of care morally for our patients, and to minimise the impact of our healthcare systems on the planet, since it in turn sustains health. Moreover, healthcare professionals interact with all sectors of society, have a global outreach and from the already existing healthcare partnerships and projects already set up, there is a pre-existing infrastructure there to disseminate information and create change.  Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels. 21/11/2012 A Week before COP18's gender day: why meeting the unmet family planning need is key for human rights, gender equality - and tackling climate changeRead Now The State of World Population Report 2012 Credit: UNFPA The State of World Population Report 2012 Credit: UNFPA The most important point made in the recent UNFPA report, The State of World Population 2012 - perhaps even its foundation - is that access to family planning is a human right. If it can be realised globally, this will be a big step not only in terms of environmental sustainability but also and more importantly, reducing poverty, exclusion, poor health and gender inequality. It is a travesty and an abuse of human rights that there are currently 222 million women without access to family planning who want it, largely for lack of a few billion dollars per year - about a tenth of the tobacco industry's annual profits. According to the UNFPA's Press Release which accompanied the report's release, making voluntary family planning available to everyone in developing countries would reduce costs for maternal and newborn health care by US$11.3 billion annually, as well as helping to stabilise the global population more quickly. In the longer term this would contribute reducing climate change (although this is not at all to imply that consumption is not at least as or probably much more important) and problems of resource scarcity. In addition to finance, to ensure that every person’s right to family planning is realised, the report also calls on governments and leaders to:

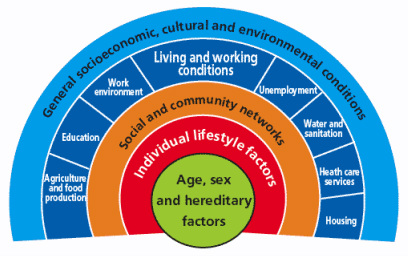

Family planning delivers immeasurable rewards to women, families, and communities by enabling healthier, longer lives. If an additional 120 million obtained access to family planning - just over half of those who currently don't have access and want it - the report estimates 3 million fewer babies would die in their first year of life. The State of World Population 2012 says that governments, civil society, health providers and communities have the responsibility to protect the right to family planning for women across the spectrum, including those who are young or unmarried. But financial resources for family planning have declined globally and contraceptive use has remained mostly steady. In 2010, donor countries fell US$ 500 million short of their expected contribution to sexual and reproductive health services in developing countries. Contraceptive use prevalence has increased globally by just 0.1 per cent per year over the last few years. Signs of progress In July, at the London Summit on Family Planning, donor countries and foundations together pledged US$2.6 billion to make family planning available to 120 million women in developing countries with unmet needs by 2020. Developing countries themselves also pledged to increase support. But, according to the report, an additional US$ 4.1 billion is necessary each year to meet the unmet need for family planning of all 222 million women who would use family planning but currently lack access to it. This investment would save lives by preventing unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions. By Shuo Zhang  Dahlgren and Whitehead model (1991) of the determinants of health [6] First published in 'Art of the Possible - the Cambridge Journal of Politics' 2011-02-13 2010 saw a year of spending cuts, riots about public sector reforms and a shift in rhetoric away from “big government” to “big society”. Fundamentally, according to the Coalition Government’s vision, the state needs to move towards leaner, meaner public services and greater freedom and individual choice. This social, institutional and political change has implications for the National Health Service (NHS) in direct and indirect ways, both as a result of the 2010 Health White Paper1 and through the impact on other services that influence wider social determinants of health. Doctors have had a mixed reaction to the new ideas, getting caught up in enticing vocabularysuch as choice and power. However, most have concerns about the risks associated with implementation. The profession faces many challenges in the years to come, not only due to changes in the demography of disease, but also changes in pensions, employment rights and training, technological and scientific innovations, and new emphasis on sustainable practice and preventative medicine. So how has the new Coalition Government approached health and will it meet the challenges for the future? Healthcare is assumed to be a pillar of society and, even in this climate of austerity, the Coalition is keen to be seen to protect the NHS. The 2010 White Paper promises real-term increases in funding, although it also stipulates the need to move towards greater efficiency and cost savings of £20 billion in the next few years. Beyond the economics, the new Health White Paper advocates structural institutional change and a shift in power towards patients and frontline professionals. In addition, public health is to become more integrated with local councils. These proposals have underlined tensions and contradictions that touch upon wider political debates about how the country should navigate this period of hardship.2 One of the most significant proposals is the introduction of the GP-led commissioning service and greater choice for patients when registering with providers. This aims to move control away from managers and towards people who know and use the system the most. This has parallels with existing patient-led support services and health activism that has broadened the health service into a user-provider network, replacing previous patriarchal structures. As an idea, a new directive that empowers patients should be welcomed; it allows them to take their health into their own hands, and could produce a system that is pro-health instead of anti-ill health. In practice, however, the implementation of these proposals may have unintended effects, such as changing the dynamics of the patient-doctor relationship, diverting more time away from patient care due to increases in paperwork and leaving the back door open for potential privatisation. This patient empowerment may also be too far down the line, and only after bad lifestyle choices have already been made, to make much difference to prevention. Furthermore, choice is often just a buzz word for the middle classes, and by creating a system whichpriorities the most vocal needs, hidden inequalities in access and treatment may emerge. A change that perhaps makes more sense is the reconstitution of public health to local authorities. This moves the remit of action for local authorities further up the chain and gives them a greater role in co-ordinating approaches across diverse sectors such as transport and education.3 In effect, it replicates approaches to public health from Victorian England when it formed a central part of town planning. This move will give the medical profession greater powers to address broader social determinants of health, but may also leave it more exposed to criticisms of state ‘nannying’. The government has also failed to consider the continuity of public health in both a community and clinical setting. Public health in clinical practice is vital in providing evidence and improving practice. Moving responsibility for aspects of public health to local councils may create discontinuity and compromise broader goals. The ring-fencing of public health funding under the Coalition signals their intention to continue to address inequalities in access and care; however, this contradicts the cuts to departments in key peripheral areas such as social care and education. To carry on business as usual is not an option. However, the proposed changes were not part of a natural evolution based around principles of adaptation and mitigation, but more of a reactionary event to a system already perturbed. The Coalition’s vision lacks coherence, and there are other ways forward in which power could be better balanced between organizations and individuals. The perspective I have gained from being involved with the climate change and health movement is one of pushing forward change and alternatives to the big picture in a subtle way: changing the way we think about health systems and social structure, changing our behaviour, and seeing savings in efficiency as opportunities rather than cuts.4 It is also a direction which embodies the ethos of ‘prosperity without growth’5 and is careful of the wider political and socio-determinants of health6. The movement realised that it had to re-frame climate change as simply an evolution for the better. For example, infrastructural and efficiency changes will have direct financial savings, with a reduction in emissions as an added bonus. On a personal level, eating less red meat and dairy products, and cycling more will have a primary health benefit as well as positive environmental impacts. In a way, we were trying to change people’s behaviour and thoughts without loading it with values and ideology. Big and, more importantly, sustainable differences can be made if small changes in perspective occur across the board. Ultimately, the danger is that the Coalition Government’s changes are ideologically driven instead of evidence-based. For these changes to be unleashed on an organization that employs 10 per cent of Britain’s workforce without initial trialling is a huge risk. If these structural changes do come into effect it will impact upon fundamental relationships between science, policy and the public. These spheres of influence, which are illustrated by figure 1, extend across individual, group and societal levels. The Coalition should be more aware of these connections. Have they done enough to ensure healthcare will be fit for the future or should we too be protesting for a new way forward? References 1 Department of Health, Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS - Health White Paper 2010, London: The Stationery Office, 2010. 2 British Medical Journal, “More brickbats than bouquets?”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c3977. 3 Anthony Kessel and Andy Haines,“What the white paper might mean for public health”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c6623. 4 Muir Gray and Frances Mortimer, “Transforming Clinical Practice”, Sustainability for health: An evidence base for action, 2 December 2009. http://www.sustainabilityforhealth.org/clinicaltransformation/opinion-pieces/transforming-clinical-practice, accessed 10 January 2011. 5 Tim Jackson 'Prosperity without Growth' (2009) Routledge ISBN-10: 1849713235 http://www.amazon.co.uk/Prosperity-without-Growth-Economics-Finite/dp/1849713235 6 G Dahlgren, M Whitehead 'Policies and strategies to promote equity in health' (1991) World Health Organization. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74737/E89383.pdf |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed