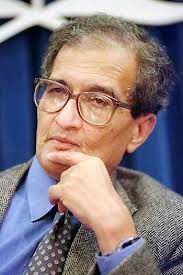

By Connor Schwartz  Amartya Sen ponders justice Amartya Sen ponders justice Climate ethics and climate justice are subjects which hide in the background of COPs and treaties, rarely given any limelight of their own. In fact, the most common appeal to climate justice within negotiations are false ones, nations setting out their stall while grasping furiously for some foundations to stand it upon. Because, while the neoliberal hegemony of self-interested actors fails miserably to encompass the breadth of human social relations, it is demonstrably accurate on an international level. Powerful nations may appeal to political theory and forms of justice to back up their positions, but you can bet that their move went outcome first, evidence second, and not the other way around. For example, in the early 2000s while America was resisting becoming party to the Kyoto Protocol, the Bush administration argued furiously that the Annex 1 countries were being unfairly asked to mitigate a crisis which, all things considered, it looked like other countries had a lot more to lose from than themselves. Slowing anthropogenic climate change will cost us a packet and only benefit Tuvalu, how unjust! It did not matter, of course, that this claim is justified only by a philosophy so libertarian that no US president (Nixon included) has ever come close to it. No, much more important to scream “injustice!” and hope nobody really notices that the argument doesn’t stack up. Thus climate ethics has been sullied and debased by negotiators wanting a transcendent justification for their greed. It’s time to put it back at the heart of a global climate regime. Here is just one such attempt. It’s not perfect but I think it reveals a few key things we are looking for from a global climate treaty, and provides the beginnings of a move away from pragmatism and towards justice. Hold tight, here comes the theory. (If you’re not interested in the theory in isolation, jump straight to part two where climate change comes back onto the scene). When we discuss distributive justice of any kind, the first thing to be argued over is what’s called the “metric” – what exactly it is we should be distributing. Let’s narrow our gaze to egalitarianism – that equality is, for some reason, at least partially good – as it is now almost universally accepted across the liberal democracies. There are two traditional camps in the metric debate: resourcists and welfarists. As their names give away, resourcists believe justice includes a focus on equalising the amount of stuff people have, whereas welfarists prefer a focus on the wellbeing or happiness people get from that stuff. It’s the classic means/ends debate. This division has been standing for hundreds of years, splitting radical feminists from their traditional colleagues and communists from conservatives. This impasse however was, I believe, broken in 1979 when Amartya Sen – a heterodox development economist from Bangladesh – gave his Tanner Lecture entitled ‘Equality of What?’. In this lecture Sen dismantled both metrics, each with a simple thought experiment, asking whether what each model was forced to conclude sounded much like justice or not. Number one. Take two agents: one able-bodied and another with a severe disability needing round the clock care. Equalise resources. After covering their care expenditure, the disabled agent has far less resources than the able bodied agent to increase their wellbeing with. Similarly other divides – gender, social position, country of birth, etc. – reach the same conclusion: that a resource egalitarian looks to be saying that justice permits, or even requires, that wellbeing is determined by factors of luck. Ask yourself: does that sound much like justice? Number two. Brian is a plumber living in the city of London and Vikram works as a dabbawalla, distributing Tiffins to the workforce of Mumbai. Brian, from any objective standpoint, enjoys a far higher standard of living than Vikram yet it is certainly conceivable that Vikram is the happier of the two. Empirically, what’s called “hedonic adaptation” shows us that as our income increases so too can our expectations, resulting in no greater happiness. So say Vikram is the happier of the two because he expects less, and we have some spare resources to distribute. We must be persuaded to give the extra to Brian. Justice? To say a poor person has no claim to extra resources because their expectations are lower doesn’t sound much like justice to me. So what does Sen suggest? Justice, he claims, is found in neither resources nor welfare, but some function between the two, some measure of how we can translate resources into welfare. The correct metric for distributive justice is a person’s capabilities or, to be specific, the capability to achieve particular substantive human functionings. Say what? Put simply, what justice demands is equalised are the real and tangible freedoms that humans can possess. It doesn’t matter how much income a person has, if they have no access to healthcare then they are not being served by justice. It does not matter how happy a person is, if they cannot access education then that is a failure of justice.  Martha C. Nussbaum Martha C. Nussbaum Although the language of capabilities was introduced by Sen, it was American theorist Martha C. Nussbaum that developed it into a robust philosophical doctrine. Borrowing from the young Marx, Nussbaum claims that justice provides entitlement to a plurality of values that are both non-aggregable and non-fungible. In other words, we cannot serve justice by simply giving all a certain amount of a certain thing – say, money – and then leaving them to make choices as to how they trade it. Rather, we must concentrate on fulfilling a range of indicators that are distinct and cannot be traded off against each other. Simplistically, one could not for example be compensated for an inadequate life expectancy by being allocated more political rights. This stands explicitly against classical and neoliberal theories of development, relying on GNP to assess the growth of a nation and the wellbeing its peoples. What’s more we do not have to earn these entitlements. They are derived from our entitlement to “the respect and dignity of a life that is fully human”. We possess them, therefore, merely due to our species membership. (Nussbaum also holds that it is likely many other species are similarly entitled to various capabilities, but for now we can just consider our entitlements on account of our being human.) That’s all well and good, but what on earth does it have to do with climate negotiations? Lots, actually. Part two focuses on bringing climate change back into the picture, and putting justice back at the heart of a global climate regime.

1 Comment

Alistair Wardrope

4/11/2013 10:38:25 pm

Glad someone's tackling climate change as a normative issue - can never understand why so much of the debate about what is to be done just brushes over the evaluative dimensions of that decision (well, I can - it's in large part the swallowing hook, line and sinker of economists' startlingly myopic claims to offer 'value-free' policy prescriptions...) Will refrain from detailed comment til the second post, but will be interested to see whether you move from the capabilities approach to questioning whether there might be more to justice simpliciter than distributive justice alone - for me, some of the most important insights of communitarian thought and relational theories of autonomy regard the constitutively social properties that need to be realised for individuals to enjoy certain 'capabilities' - and the normative significance of these properties can be neglected in an individualising paradigm such as distributive justice.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed