|

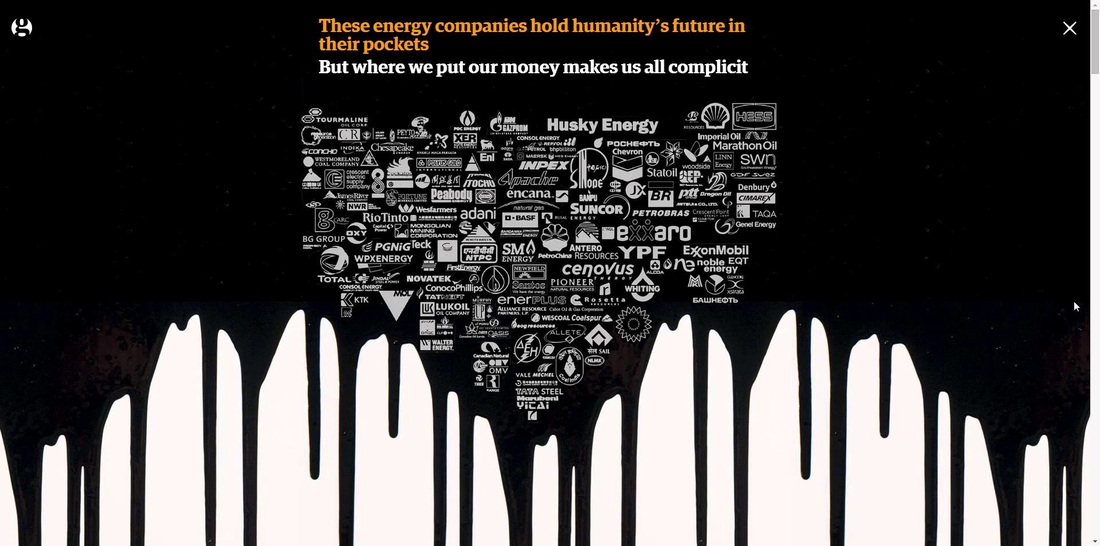

You may have noticed a running theme in the posts on the HPblog recently; we’ve been working a lot on divestment – convincing the health sector to stop funding the companies driving climate change, and instead to take its commitment to ‘do no harm’ seriously and move its money towards those working to achieve the energy transition our planet and our health requires. Health sector divestment has taken a huge step forward in the past month, since the Guardian newspaper launched its ‘Keep it in the Ground’ campaign, calling for divestment from the fossil fuel industry. What’s particularly notable about the campaign is their chosen targets – the two biggest private global health funding organisations in the world, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. It’s hard for anyone with more than a passing interest in global health to criticise the Wellcome Trust; Wellcome-funded research has achieved extraordinary advances in healthcare. They are more willing than others to fund research involving higher levels of risk, complexity and uncertainty, an approach typified by their making exploration of the connections between environment, nutrition and health one of their five ‘key challenges’. Moreover, their commitment to transparency – whether in championing open access to scientific research or in making the details of their investments freely available to the public – pervades all the Trust’s actions. But there would be little virtue in such openness if none were willing to challenge them when mistaken. Their stance on continued investment in the fossil fuel industry – as outlined in a recent Guardian article by Director Jeremy Farrar – demands such a challenge. We agree with much of what Farrar has to say. That climate change, as one of the greatest threats to global health of the 21st century, demands concerted action from health organisations. That this requires a commitment to a rapid decarbonisation of the global economy in order to remain within a 2C warming carbon budget. And that consideration of the impacts on human health and wellbeing need to be at the forefront in planning a just and sustainable transition. However, where we disagree is in the role of fossil fuels – and the fossil fuel industry – in making that transition.

He also proposes that it is from within the fossil fuel industry that the necessary decarbonisation will come, and the best way to achieve that is from within, as an active and engaged shareholder. But it is difficult to see how shareholder engagement alone could bring about the scale of transition needed with the required urgency (the IPCC’s 2C carbon budget will be exhausted by 2036 at current rates). Health institutions, more than any other organisations, should be aware that businesses stop responding to shareholder engagement when that engagement challenges the very core of their business model – it’s why it failed with the tobacco industry, and why it’s failing now with fossil fuels. Farrar is optimistic about the role of fossil fuels in a low-carbon economy – citing natural gas and carbon capture and storage as central components – but it is hard to reconcile this position with evidence that half of already-known gas reserves will have to remain unburned to stay under 2C, and that CCS will do nothing to alleviate the health burden of particulate air pollution.

Nonetheless, selective engagement may have its place alongside divestment. But it is only possible with companies who display a realistic commitment to keeping warming under 2C – one that moves beyond words. We applaud the Trust’s acknowledgement of the inconsistency of coal and tar sands development with a healthy climate. But so too is pursuing Arctic drilling, not to mention funding attempts to undermine climate science or legislative efforts on mitigation policy – of which companies in which the Trust invests are guilty. For companies that fall short of the required action, divestment must follow. While we focus here on the Wellcome Trust, that is only because their commitment to public debate permits us to engage in this conversation. The same arguments apply to all health sector organisations, who share the same responsibilities for health of people and planet alike. If, like us, you're convinced that it's time for health organisations to ditch their dirty investments, here are a few things you can do:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed