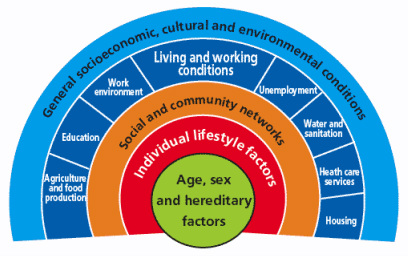

By Shuo Zhang  Dahlgren and Whitehead model (1991) of the determinants of health [6] First published in 'Art of the Possible - the Cambridge Journal of Politics' 2011-02-13 2010 saw a year of spending cuts, riots about public sector reforms and a shift in rhetoric away from “big government” to “big society”. Fundamentally, according to the Coalition Government’s vision, the state needs to move towards leaner, meaner public services and greater freedom and individual choice. This social, institutional and political change has implications for the National Health Service (NHS) in direct and indirect ways, both as a result of the 2010 Health White Paper1 and through the impact on other services that influence wider social determinants of health. Doctors have had a mixed reaction to the new ideas, getting caught up in enticing vocabularysuch as choice and power. However, most have concerns about the risks associated with implementation. The profession faces many challenges in the years to come, not only due to changes in the demography of disease, but also changes in pensions, employment rights and training, technological and scientific innovations, and new emphasis on sustainable practice and preventative medicine. So how has the new Coalition Government approached health and will it meet the challenges for the future? Healthcare is assumed to be a pillar of society and, even in this climate of austerity, the Coalition is keen to be seen to protect the NHS. The 2010 White Paper promises real-term increases in funding, although it also stipulates the need to move towards greater efficiency and cost savings of £20 billion in the next few years. Beyond the economics, the new Health White Paper advocates structural institutional change and a shift in power towards patients and frontline professionals. In addition, public health is to become more integrated with local councils. These proposals have underlined tensions and contradictions that touch upon wider political debates about how the country should navigate this period of hardship.2 One of the most significant proposals is the introduction of the GP-led commissioning service and greater choice for patients when registering with providers. This aims to move control away from managers and towards people who know and use the system the most. This has parallels with existing patient-led support services and health activism that has broadened the health service into a user-provider network, replacing previous patriarchal structures. As an idea, a new directive that empowers patients should be welcomed; it allows them to take their health into their own hands, and could produce a system that is pro-health instead of anti-ill health. In practice, however, the implementation of these proposals may have unintended effects, such as changing the dynamics of the patient-doctor relationship, diverting more time away from patient care due to increases in paperwork and leaving the back door open for potential privatisation. This patient empowerment may also be too far down the line, and only after bad lifestyle choices have already been made, to make much difference to prevention. Furthermore, choice is often just a buzz word for the middle classes, and by creating a system whichpriorities the most vocal needs, hidden inequalities in access and treatment may emerge. A change that perhaps makes more sense is the reconstitution of public health to local authorities. This moves the remit of action for local authorities further up the chain and gives them a greater role in co-ordinating approaches across diverse sectors such as transport and education.3 In effect, it replicates approaches to public health from Victorian England when it formed a central part of town planning. This move will give the medical profession greater powers to address broader social determinants of health, but may also leave it more exposed to criticisms of state ‘nannying’. The government has also failed to consider the continuity of public health in both a community and clinical setting. Public health in clinical practice is vital in providing evidence and improving practice. Moving responsibility for aspects of public health to local councils may create discontinuity and compromise broader goals. The ring-fencing of public health funding under the Coalition signals their intention to continue to address inequalities in access and care; however, this contradicts the cuts to departments in key peripheral areas such as social care and education. To carry on business as usual is not an option. However, the proposed changes were not part of a natural evolution based around principles of adaptation and mitigation, but more of a reactionary event to a system already perturbed. The Coalition’s vision lacks coherence, and there are other ways forward in which power could be better balanced between organizations and individuals. The perspective I have gained from being involved with the climate change and health movement is one of pushing forward change and alternatives to the big picture in a subtle way: changing the way we think about health systems and social structure, changing our behaviour, and seeing savings in efficiency as opportunities rather than cuts.4 It is also a direction which embodies the ethos of ‘prosperity without growth’5 and is careful of the wider political and socio-determinants of health6. The movement realised that it had to re-frame climate change as simply an evolution for the better. For example, infrastructural and efficiency changes will have direct financial savings, with a reduction in emissions as an added bonus. On a personal level, eating less red meat and dairy products, and cycling more will have a primary health benefit as well as positive environmental impacts. In a way, we were trying to change people’s behaviour and thoughts without loading it with values and ideology. Big and, more importantly, sustainable differences can be made if small changes in perspective occur across the board. Ultimately, the danger is that the Coalition Government’s changes are ideologically driven instead of evidence-based. For these changes to be unleashed on an organization that employs 10 per cent of Britain’s workforce without initial trialling is a huge risk. If these structural changes do come into effect it will impact upon fundamental relationships between science, policy and the public. These spheres of influence, which are illustrated by figure 1, extend across individual, group and societal levels. The Coalition should be more aware of these connections. Have they done enough to ensure healthcare will be fit for the future or should we too be protesting for a new way forward? References 1 Department of Health, Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS - Health White Paper 2010, London: The Stationery Office, 2010. 2 British Medical Journal, “More brickbats than bouquets?”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c3977. 3 Anthony Kessel and Andy Haines,“What the white paper might mean for public health”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c6623. 4 Muir Gray and Frances Mortimer, “Transforming Clinical Practice”, Sustainability for health: An evidence base for action, 2 December 2009. http://www.sustainabilityforhealth.org/clinicaltransformation/opinion-pieces/transforming-clinical-practice, accessed 10 January 2011. 5 Tim Jackson 'Prosperity without Growth' (2009) Routledge ISBN-10: 1849713235 http://www.amazon.co.uk/Prosperity-without-Growth-Economics-Finite/dp/1849713235 6 G Dahlgren, M Whitehead 'Policies and strategies to promote equity in health' (1991) World Health Organization. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74737/E89383.pdf

0 Comments

|

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed