The plenary room in Bonn (from UNclimatechange on Flickr) The plenary room in Bonn (from UNclimatechange on Flickr) Gabriele Messori The United Nations’ climate negotiations usually gain the press spotlight once a year, when the big Conference of the Parties (COP) meeting takes place. However, the process of designing a global climate agreement is ongoing, and additional meetings are scheduled throughout the year. One such meeting is currently taking place in Bonn. The meeting addresses a broad range of topics, among which mitigation, adaptation, climate equity and climate finance. All of these are crucial for minimizing the social and economic impacts of climate change, and all can reduce the severe health footprint that a changing climate inevitably has. There is a wide consensus that time is running out and the meeting’s co-chair, Mr. Runge-Metzger, warned that if no decisive action is taken we could be looking at a 4 ˚C warming by the end of the century. This would spell catastrophe for the most vulnerable countries, such as small island states and least developed countries, Because of this, the least developed and developing countries are demanding that the developed countries step forward and take the lead, both in terms of national plans to reduce emissions and in providing climate finance. As eloquently stated by the Philippines, “In our delegation we do not speak of support... finance is a commitment by developed countries, not support.” In line with the feeling that the time is ripe for decisive action, it was decided to establish a formal negotiation group, called “contact group” in UN jargon, to continue the work on a global climate treaty. This decision will come into effect in June, when the parties will meet again to proceed with the negotiations. This is a distinct step forwards from the informal consultations that have taken place for the last two years. Besides this, however, the meeting in Bonn has had few concrete outcomes. The talks have been plagued by clashes over procedural and organizational issues, which have often overshadowed the central point of the negotiations, namely climate change. With time running out and the aim to have an ambitious global climate treaty in place by 2015, every second of negotiating time is precious. Today is the final day of meetings here in Bonn, and we all hope it will end on a positive note, preparing the ground for the next round of talks in June.

0 Comments

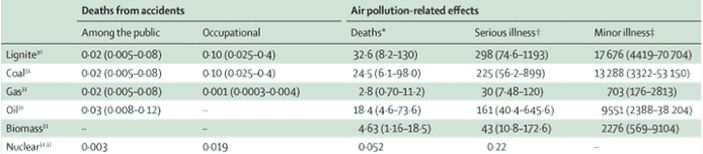

Gabriele Messori and Izzy Braithwaite Adapted from a blog post at http://climatesnack.com/2014/01/30/cough-for-coal-at-cop19/#more-1673  Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Neither of us had imagined we’d end up carrying a pair of giant pink lungs in front of the Polish Ministry of Economy on a cold November morning. Why were we there? It’s a long story… We were in Warsaw for COP19, the annual UN climate talks (COP = Conference of the Parties). The aim of the talks is to reach a global deal to tackle climate change in 2015, which will come into force in 2020. We went as part of a delegation of students from Healthy Planet UK, a small, student-led group which seeks to raise awareness about the links between climate and health, and to advocate for UK policy that benefits both health and the environment. As students, researchers and young people, our motivation was the growing body of evidence that climate change poses a major threat to global health, and that sustainable development presents major opportunities for public health. Examples of such climate-health synergies (sometimes called health ‘co-benefits’) can be found across energy, transport, housing and food policy – and quite possibly elsewhere too. Air pollution – bad for health, bad for the climate We know that greenhouse gas emissions affect health indirectly through their contribution to climate change, via changing temperatures and rainfall patterns. Although carbon dioxide has no direct health effect except at high concentrations, it is often, if not invariably, produced alongside other air pollutants. These include substances such as particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen and sulphur oxides, which are emitted both in energy production and motorised transport. Some are greenhouse gases themselves, and all are harmful to our health with myriad effects on our lungs, blood vessels and even cancer risk. The cumulative impact of chronic exposure shortens lives and exacerbates a range of other medical conditions. Around the world, man-made outdoor air pollution accounts for an estimated 2.5 million excess deaths every year. Indoor air pollution (much of it from inefficient cookstoves) accounts for at least as many again, which means that overall air pollution is one of the leading killers globally. Lessons about how politics works… Given the clear evidence that air pollution from burning fossil fuels is so bad for health, combined with the urgency of tackling climate change, you might think governments would be rushing to capitalise on those win-wins. This is where the inflatable lungs come in. Whilst some countries are already taking the kinds of steps that we need, cutting emissions and simultaneously reducing air pollution, over the course of the talks it became fairly clear that some others are working very hard to promote a fossil-fuel dependent future. Almost all of the conference sponsors were fossil-fuel intensive industries. Even more astonishingly, just one day after a summit on climate change and health, organised by the newly-formed Global Climate and Health Alliance, the Polish Ministry of Economy hosted an “International Coal and Climate” summit in parallel with the COP. Feeling that this was outrageous, our team joined many other groups to take part in ‘Cough4Coal’: a public action staged outside the Coal Summit. The stunt involved a series of scenes alternating with speakers from Poland, the Philippines and the UK – one of our team – with the impressive accompaniment of a 7m tall pair of lungs. This was intended to be a visual symbol of the direct health impacts of burning fossil fuels, but also of the less direct health impacts of climate change. Tip of the iceberg

Climate change has been described as “the greatest global health threat of the 21stCentury” by the leading medical journal The Lancet. A 2012 analysis by the DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor arrived at a total of 400,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2010, the greatest burden within this being due to hunger and diarrhoeal disease. However, it is by no means clear that it is accurate to simply extrapolate the future burden due to climate change from the impacts seen so far. These may well be the tip of the iceberg, given that we’ve only seen limited warming relative to what is projected for the coming century. What are the main health impacts of climate change? They range from increased heat exposure, a particular problem among older people and manual labourers, to extreme weather events (which can often affect mental health particularly severely). Changes in the distributions of infectious diseases, and malnutrition and/or starvation due to effects on food production, are equally important. The indirect impacts, such as exacerbation of poverty, migration, and conflict, are both harder to attribute to climate change and significantly harder to forecast. Such impacts are likely to be non-linear and could well be very large indeed – especially with the levels of warming scientists are currently projecting in business-as-usual scenarios. For those interested in finding out more about the health impacts of climate change, we've compiled a summary here. Bridging the gap There may also be pragmatic reasons for framing climate change as a health threat; namely that it connects to people’s own lives and the things they value. In a 2012 study by Teresa Myers and colleagues, a test audience was presented with articles that discussed climate change from a range of different perspectives. Right across audience segments, the articles emphasising the health frame were more likely to elicit strong support for mitigation and adaptation policies than those focusing on the environment or national security. The second working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s fifth assessment report will include a substantial chapter on human health, which could present a useful opportunity for more public communication about climate change using the health frame. It is clear that the stakes are high for health if we continue on our current path. The evidence that action on climate change can benefit public health in all regions is strong – and growing. Emphasising the health implications of climate change can be a powerful way to engage a wider audience in the issue, and everyone with an interest in human health, or just the future of our planet, has a role to play. Not to suggest that you’d need to carry any giant lungs in front of government departments – though by all means get in touch if you’d like to…  The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) Izzy Braithwaite Originally published at: http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/comment-health-overlooked-in-our-response-to-climate-change/ The protection of human health and wellbeing is a central rationale for the emissions reductions called for in the very first article of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Yet, somehow, the issue is missing from many parts of the UN talks. The growing body of research and evidence in the area over the past couple of decades hasn’t really translated into a broader understanding of how climate change and health are related, beyond a relatively small community of academics and health professionals. Knowledge about the links between climate and health among the public, climate negotiators and environmentalists is often limited and quite superficial. It typically doesn’t stretch far beyond the more direct impacts, such as heatwaves, vector-borne diseases or extreme weather events such as flooding. Indirect effects on health are rarely considered, and both the media and the public tend to frame the impacts of climate change in terms of the risks to ecosystems and species or economic losses; very rarely in terms of its other impacts on people and their health. Perhaps this is part of why climate mitigation and adaptation measures fail to get the levels of both political and financial support they need to tackle climate change and to protect and promote health in the face of it: current levels of adaptation finance, much like current emissions reductions pledges, are grossly inadequate. As a glance at any newspaper or polls about the relative political importance of different topics make clear – most of us are concerned about our own health and the health of those we care about, including that of our children and grandchildren and less visible problems like climate change, which are also delayed in time, often feature far below this on the agenda. Climate change will dramatically affect the health of today’s children and young people, and more than that, policies to promote the health ‘co-benefits’ of sustainability and climate action could greatly improve health. Surely those messages, if communicated more effectively, could be a strong driver to help us achieve the sort of rapid, meaningful changes we need in order to avoid catastrophic climate change - couldn’t they? In the UK, several thousand health professionals have joined the Climate and Health Council to add their voice to a global climate and health movement which already has strong voices in Australia, Europe and the US, along with several other regions, and they are starting to connect up, for example with the Doha Declaration. Doubt is their product... At the same time, communication with negotiators, the mainstream media and the wider public around what’s known about climate and health clearly hasn’t yet been very effective, and has been compounded by the confusion that biased and inaccurate media such as Fox News and the Murdoch empire seek to create. This is very much like the 'merchants of doubt' phenomenon that emerged among tobacco companies as the evidence of tobacco's health risks came to light. One of my friends recently asked me when he saw this video, “if climate change is really such a big health threat, then why don’t most people know that, and why isn’t it mentioned more in the news?” I’m convinced by the evidence that it is – some of it is collected in our resources section– but I found it hard to answer his question. Have we all, consciously or subconsciously, decided that it’s too depressing so we don’t want to know, do the media decide it’s not worth broadcasting, is it related to the success of fossil fuel companies and their PR and lobbying teams, or is it something else? I don’t have the answers, but I think there are many reasons: for one, picking out long-term trends to ascertain what health impacts are attributable to climate change is no easy task, and – especially when it comes to modelling future health impacts which are often highly dependent on socioeconomic factors too – the science is far from simple. Predictions, of necessity, depend on various assumptions and on multiple interacting factors. As with climate change in general, the real-world effects are highly uncertain: not because scientists think health might be fine in a world four or six degrees hotter, but because it’s very hard to work out exactly how bad the impacts may be. Even the World Bank now explicitly recognises that this is what we’re currently on course towards, that it’ll be far from easy to adapt to, and that such a temperature rise would conflict greatly with its mission to alleviate poverty. The dangers of ignoring Black Swans As George Monbiot pointed out in characteristically optimistic style last year, mainstream global predictions for future food availability in the face of climate change may be wildly off – because they’re based only on average temperatures rather than the extremes. A fatal error if this is true that the extremes – droughts, wildfires and so on – could become the main determinant of global food production, interacting with other changes to affect in ways that, like Taleb's 'Black Swan' events, are almost impossible to predict. If this does turn out to be the case, it’s likely that by far the biggest health impact of climate change will be malnutrition, as argued by Kris Ebi, lead author of the human health section of the last IPCC report. Inadequate food intake not only increases vulnerability to infectious diseases such as malaria, TB, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease, but also kills directly through starvation. Food insecurity, in turn, can force people to migrate just as something more obvious like sea-level rise can, and this can be a driver of civil conflict. Both migration and conflict of course have major physical and health impacts, but their extent and distribution depend on numerous other things; climate is one driver among many. Like any give extreme weather event, it’s hard to attribute indirect effects of climate change such as these to climate change, given how strongly it interacts with other contextual factors. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a causal relationship. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment showed in 2005, our health and wellbeing ultimately depends on ecosystem functioning and stability, at levels from local to global. How ecosystems and in turn health are being – and will be – affected by climate change is unavoidably complex. That makes it hard to communicate and hard to use to change policy, but we cannot allow this to stop effective advocacy and action. The fossil fuel industries and the many dubious institutions and individuals they fund will not wait: with billions made from the sale of coal, oil and gas, they are much better organised and resourced than us at present, and they will use every opportunity to maintain doubt, prolong inaction and ensure that our future isn’t allowed to compromise their sales. In order to extend a sense of the importance of climate action beyond the environmental community and to secure broad and deep consensus on the need for concerted action, health must play a much bigger role in decision-making at all levels. Both impacts and health co-benefits need to feature more centrally in national mitigation and adaptation plans, and in our discussions around climate change more generally. That shift won’t happen on its’ own, and with the Bonn UNFCCC intersessionals coming up in June, it strike me that health should be a priority. Better resourcing and a comprehensive work programme including capacity-building, education and raising public awareness on subjects specific to climate and health would be a tangible and positive way to protect and promote health and to reduce the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable. Jonny Elliott, from COP18 We've all been there... if you're anything like me, you probably thought you had climate change sussed when you learnt the difference between your NO2 and your CO2, that simple greenhouse effect diagram they teach you about in GCSE Chemistry, or felt like a genius amongst mere mortals when the Kyoto Protocol was mentioned in conversation. But then you're asked for your views on the Bali Roadmap, or a sample NAPA for a non-annex country, and suddenly you've gone blank and all you can muster is a smile... Welcome to Doha, and to the 18th UN Conference on Climate Change.  Over the next two weeks, I hope to be able to share with you the ins and outs of what can certainly be a tricky process to get your head around: but don’t let that put you off. I am by no means an expert on the whole UNFCCC process - but as Christiana Figueres, the Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC reiterated earlier at an event this week, ‘none of us are, but we all have our niche.’ As a health professional I strongly agree with the UCL-Lancet commission's statement that ‘Climate change could be the biggest global health threat of the 21st century’ . Our health is essentially dependent on stable, functioning ecosystems and a healthy biosphere. This bedrock for global health is under enormous threat from climate change and ecological damage that we are causing. I don’t know about you, but I’ve known about this problem for quite a few years since early secondary school, but have generally felt powerless to act - and at times questioned whether my efforts would really have an effect. However, as I have connected more deeply with other social justice issues, development and public health I've found that the message of climate change and the irrefutable science behind it keeps reappearing. This isn’t just confined to articles we read on PubMed or the Lancet, but is important in our daily lives. It's there in extreme weather events, such as a record-breaking heat wave that I experienced in Washington D.C.; quite possible the flooding that inundated the streets of my hometown Belfast this summer and saw an unlikely hero on a surfboard rescue victims from their homes; the flooding happening across the UK. And it's there in the general trends too. As students, healthcare professionals and people interested in global health, I believe that engaging with this issue really is a case of now or never. We are in a situation in the UK where most are aware of climate change, but all too often turn a blind eye. This is an unavoidable moral responsibility and an issue that will affect ourselves and our children: it's not something in the distant future, it's already happening. And we have to act fast. I urge you over the coming days and weeks to take a second take at what climate change means for you, your family and every single person on this planet. Join me on the journey in Doha where I’ll be creating a bit of a stir on the ground; meeting with negotiators, delivering workshops, training young people from all over the world and leading publicity events such as flashmobs. Forging partnerships and trying to be as accessible as I can will be my allies. Drop me a line, follow me on facebook, or send me a tweet and let’s create a huge wave of change at the UN. It’s our responsibility, so let’s act now! Below: Jonny on the ground in Doha partnering with IFMSA (left) to plan a stunt and with Ex-President of Ireland, Mary Robinson (right)  Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels. Jonny Meldrum The UN climate talks were an exhausting, turbulent and yet thrilling time. Reading the lack of coverage in the British press – on the occasions we tried to find out what was happening in the outside world – was always a shock to the complete immersion we experienced in Durban. Everything centred around the negotiations. We read COP17, we talked COP17, we campaigned COP17, we wrote COP17. Christ, we even slept COP17. Now it’s time to document our journey. The Kenyan Youth Climate Caravan (or 6 trucks to be more precise) travelled from Nairobi to Durban over 42 days, carrying 161 climate activists from 18 countries. On the way they performed in local concerts and rallies, engaging and mobilising communities. At their arrival at the Conference of Youth they entered in the room in style to perform to other youth activists from all around the World. It was incredible. Throughout Durban Medsin worked closely with the International Federation of Medical Student Associations (IFMSA), the World Health Organisation and other international health NGOs, to raise awareness of the massive health impacts of climate change and ensuring that the protection of health is an integral part of adaption measures, where countries prepare for the effects of climate change we know are on the way. This year saw the inaugural Climate and Health Summit held in Durban. Opened by the South African Secretary of State for Health, followed by a day of plenaries and panel discussions with experts from the World Health Organisation, Health Care Without Harm and more, the Summit concluded with a Durban Declaration on Climate and Health, signed by hundreds of healthcare professionals, government ministers and summit delegates. This declaration was released in a press conference during which Medsin and the IFMSA staged a demonstration where we took the temperature of the Earth. We felt whilst in South Africa, a country wrought with AIDS, it was of the upmost importance that we highlighted this link. So, to commemorate World AIDS Day, we formed a red human ribbon around the Earth. We gained significant media attention, including coverage on CNN and gave television interviews to broadcasters from around the World. At the end of each day civil society awards the most obstructive country in the talks a ‘fossil’. Countries hate this public shaming and there’s often an official response from government ministers. Here, Canada is awarded 1st place, early on in the conference, not only for refusing to renew their commitments in the Kyoto Protocol, but also entering the week saying they were here to play hard-ball with developing countries whom they were ‘sick of playing the guilt card’. You couldn’t make this stuff up. HOWEVER. The Canadian Youth Delegation, embarrassed and outraged by their country’s behaviour, made it clear throughout the conference that their government were acting on behalf of polluters and not the Canadian people. During the opening statement of their environmental minister at the negotiating plenary, 6 Canadian young people stood up and turned their back on Canada, and were subsequently ‘debadged’ and removed from the conference centre. Many official government delegates from other countries broke into applause and the Canadian minister was visibly shaken. The next day, Abigail Borah, part of the US youth delegation, stood up during the speech of Todd Stern and interrupted the lead US negotiator in an intervention on behalf of the America people: “They cannot speak on behalf of the United States of America … the obstructionist Congress has shackled a just agreement and delayed ambition for far too long.” On the scheduled final day Anjali Appadurai, from Earth in Brackets, delivered an impassioned and powerful speech on behalf of the young constiuency. Afterwards she moved away from the podium and shouted ‘mic check’. This prompted 50 young people spread around the plenary room to stand up and repeat ‘mic check’ in unison. After another mic check she shouted the following: (the italics are the human microphone effect in repetition). Yet again, a significant majority of the government ministers in the room stood and this time gave our intervention a standing ovation, sending a clear message for stronger action. Equity now. You’ve run out of excuses. And we’re running out of time. Get it done. On the last official day of negotiations civil society took an unprecedented stand in solidarity with Africa and Small Island States, representing some of the people most vulnerable to climate change. Hundreds of civil society delegates held a massive protest and went into occupation of the conference centre, right outside the plenary room where ministers were negotiating. Government ministers from the Maldives and a number of African countries joined us and we then escorted them into the negotiation session. The momentum generated was incredible – many negotiators told us that this stand allowed them to push for stronger action inside the hall.  Negotiations continued long into the night from the scheduled end on Friday evening, through Saturday and reaching a conclusion around 5am on Sunday. The major issues surrounded the renewal of the Kyoto Protocol and the roadmap to a future climate deal. Previously the big emerging economies of China, Brazil and India had refused to commit to legally binding targets as part of this future treaty. In the early hours of Sunday morning the South Africa chair of the plenary asked the EU and India to form a huddle to reach an agreement on the legal status of a future deal. This picture was taken metres from the action (- note our very own Chris Huhne centre-right). Brazil suddenly came up with the wording ‘Agreed outcome with legal force’ which both India and EU (and other countries) agreed to, at which point the South Africa chair ran off in much relief to adopt the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. Importantly this means that a future deal, to be agreed by 2015 and implemented in 2020, will be legally binding for all countries. This is good news considering the expectations going into the final days of the conference. However, it’s important to remember there’s still a massive gap in the action required now to safeguard the future survival of millions of people. We’re not done yet. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed