|

You may have noticed a running theme in the posts on the HPblog recently; we’ve been working a lot on divestment – convincing the health sector to stop funding the companies driving climate change, and instead to take its commitment to ‘do no harm’ seriously and move its money towards those working to achieve the energy transition our planet and our health requires. Health sector divestment has taken a huge step forward in the past month, since the Guardian newspaper launched its ‘Keep it in the Ground’ campaign, calling for divestment from the fossil fuel industry. What’s particularly notable about the campaign is their chosen targets – the two biggest private global health funding organisations in the world, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. It’s hard for anyone with more than a passing interest in global health to criticise the Wellcome Trust; Wellcome-funded research has achieved extraordinary advances in healthcare. They are more willing than others to fund research involving higher levels of risk, complexity and uncertainty, an approach typified by their making exploration of the connections between environment, nutrition and health one of their five ‘key challenges’. Moreover, their commitment to transparency – whether in championing open access to scientific research or in making the details of their investments freely available to the public – pervades all the Trust’s actions. But there would be little virtue in such openness if none were willing to challenge them when mistaken. Their stance on continued investment in the fossil fuel industry – as outlined in a recent Guardian article by Director Jeremy Farrar – demands such a challenge. We agree with much of what Farrar has to say. That climate change, as one of the greatest threats to global health of the 21st century, demands concerted action from health organisations. That this requires a commitment to a rapid decarbonisation of the global economy in order to remain within a 2C warming carbon budget. And that consideration of the impacts on human health and wellbeing need to be at the forefront in planning a just and sustainable transition. However, where we disagree is in the role of fossil fuels – and the fossil fuel industry – in making that transition.

He also proposes that it is from within the fossil fuel industry that the necessary decarbonisation will come, and the best way to achieve that is from within, as an active and engaged shareholder. But it is difficult to see how shareholder engagement alone could bring about the scale of transition needed with the required urgency (the IPCC’s 2C carbon budget will be exhausted by 2036 at current rates). Health institutions, more than any other organisations, should be aware that businesses stop responding to shareholder engagement when that engagement challenges the very core of their business model – it’s why it failed with the tobacco industry, and why it’s failing now with fossil fuels. Farrar is optimistic about the role of fossil fuels in a low-carbon economy – citing natural gas and carbon capture and storage as central components – but it is hard to reconcile this position with evidence that half of already-known gas reserves will have to remain unburned to stay under 2C, and that CCS will do nothing to alleviate the health burden of particulate air pollution.

Nonetheless, selective engagement may have its place alongside divestment. But it is only possible with companies who display a realistic commitment to keeping warming under 2C – one that moves beyond words. We applaud the Trust’s acknowledgement of the inconsistency of coal and tar sands development with a healthy climate. But so too is pursuing Arctic drilling, not to mention funding attempts to undermine climate science or legislative efforts on mitigation policy – of which companies in which the Trust invests are guilty. For companies that fall short of the required action, divestment must follow. While we focus here on the Wellcome Trust, that is only because their commitment to public debate permits us to engage in this conversation. The same arguments apply to all health sector organisations, who share the same responsibilities for health of people and planet alike. If, like us, you're convinced that it's time for health organisations to ditch their dirty investments, here are a few things you can do:

0 Comments

Yesterday evening marked the launch of Unhealthy Investments, the report on climate change, global health and the fossil fuel industry. Medact and Healthy Planet produced this report, published alongside the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, the Climate and Health Council, and medsin, as a tool to help health workers make the case for their representative bodies, funders, and other health sector institutions to divest from the fossil fuel industry. The report argues that:

There has been significant coverage of the report’s launch in various venues.

What now? This is only the beginning; the report and related resources, and the coverage and debate surrounding it, provide the perfect tools for healthcare students and health workers to take the case for divestment – and action on the health impacts of climate change – to their universities, trusts, unions, professional organisations, representative bodies, and other representatives of the health community. How can we go about doing this? Some ideas:

For more on divestment and health, visit the Unhealthy Investments report site: www.unhealthyinvestments.uk.

Gabriele Messori and Izzy Braithwaite Adapted from a blog post at http://climatesnack.com/2014/01/30/cough-for-coal-at-cop19/#more-1673  Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Neither of us had imagined we’d end up carrying a pair of giant pink lungs in front of the Polish Ministry of Economy on a cold November morning. Why were we there? It’s a long story… We were in Warsaw for COP19, the annual UN climate talks (COP = Conference of the Parties). The aim of the talks is to reach a global deal to tackle climate change in 2015, which will come into force in 2020. We went as part of a delegation of students from Healthy Planet UK, a small, student-led group which seeks to raise awareness about the links between climate and health, and to advocate for UK policy that benefits both health and the environment. As students, researchers and young people, our motivation was the growing body of evidence that climate change poses a major threat to global health, and that sustainable development presents major opportunities for public health. Examples of such climate-health synergies (sometimes called health ‘co-benefits’) can be found across energy, transport, housing and food policy – and quite possibly elsewhere too. Air pollution – bad for health, bad for the climate We know that greenhouse gas emissions affect health indirectly through their contribution to climate change, via changing temperatures and rainfall patterns. Although carbon dioxide has no direct health effect except at high concentrations, it is often, if not invariably, produced alongside other air pollutants. These include substances such as particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen and sulphur oxides, which are emitted both in energy production and motorised transport. Some are greenhouse gases themselves, and all are harmful to our health with myriad effects on our lungs, blood vessels and even cancer risk. The cumulative impact of chronic exposure shortens lives and exacerbates a range of other medical conditions. Around the world, man-made outdoor air pollution accounts for an estimated 2.5 million excess deaths every year. Indoor air pollution (much of it from inefficient cookstoves) accounts for at least as many again, which means that overall air pollution is one of the leading killers globally. Lessons about how politics works… Given the clear evidence that air pollution from burning fossil fuels is so bad for health, combined with the urgency of tackling climate change, you might think governments would be rushing to capitalise on those win-wins. This is where the inflatable lungs come in. Whilst some countries are already taking the kinds of steps that we need, cutting emissions and simultaneously reducing air pollution, over the course of the talks it became fairly clear that some others are working very hard to promote a fossil-fuel dependent future. Almost all of the conference sponsors were fossil-fuel intensive industries. Even more astonishingly, just one day after a summit on climate change and health, organised by the newly-formed Global Climate and Health Alliance, the Polish Ministry of Economy hosted an “International Coal and Climate” summit in parallel with the COP. Feeling that this was outrageous, our team joined many other groups to take part in ‘Cough4Coal’: a public action staged outside the Coal Summit. The stunt involved a series of scenes alternating with speakers from Poland, the Philippines and the UK – one of our team – with the impressive accompaniment of a 7m tall pair of lungs. This was intended to be a visual symbol of the direct health impacts of burning fossil fuels, but also of the less direct health impacts of climate change. Tip of the iceberg

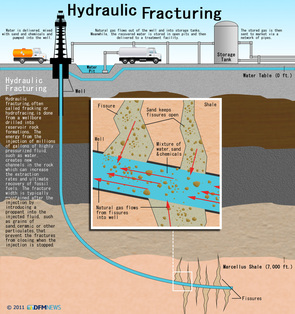

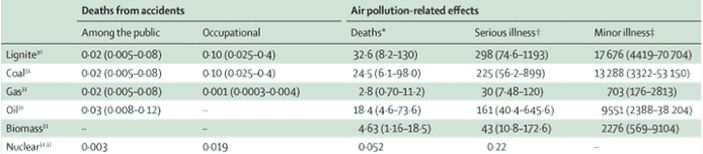

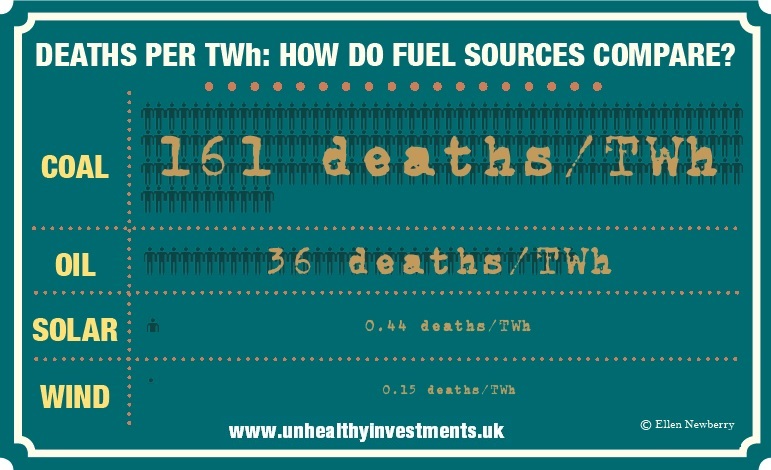

Climate change has been described as “the greatest global health threat of the 21stCentury” by the leading medical journal The Lancet. A 2012 analysis by the DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor arrived at a total of 400,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2010, the greatest burden within this being due to hunger and diarrhoeal disease. However, it is by no means clear that it is accurate to simply extrapolate the future burden due to climate change from the impacts seen so far. These may well be the tip of the iceberg, given that we’ve only seen limited warming relative to what is projected for the coming century. What are the main health impacts of climate change? They range from increased heat exposure, a particular problem among older people and manual labourers, to extreme weather events (which can often affect mental health particularly severely). Changes in the distributions of infectious diseases, and malnutrition and/or starvation due to effects on food production, are equally important. The indirect impacts, such as exacerbation of poverty, migration, and conflict, are both harder to attribute to climate change and significantly harder to forecast. Such impacts are likely to be non-linear and could well be very large indeed – especially with the levels of warming scientists are currently projecting in business-as-usual scenarios. For those interested in finding out more about the health impacts of climate change, we've compiled a summary here. Bridging the gap There may also be pragmatic reasons for framing climate change as a health threat; namely that it connects to people’s own lives and the things they value. In a 2012 study by Teresa Myers and colleagues, a test audience was presented with articles that discussed climate change from a range of different perspectives. Right across audience segments, the articles emphasising the health frame were more likely to elicit strong support for mitigation and adaptation policies than those focusing on the environment or national security. The second working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s fifth assessment report will include a substantial chapter on human health, which could present a useful opportunity for more public communication about climate change using the health frame. It is clear that the stakes are high for health if we continue on our current path. The evidence that action on climate change can benefit public health in all regions is strong – and growing. Emphasising the health implications of climate change can be a powerful way to engage a wider audience in the issue, and everyone with an interest in human health, or just the future of our planet, has a role to play. Not to suggest that you’d need to carry any giant lungs in front of government departments – though by all means get in touch if you’d like to…  Emily Collins, medical student at Keele University If you’ve seen the news recently, you’ll probably have heard many loud opinions battling to have their say on fracking. Fracking is a process that is unfamiliar to most of us, but which could have big effects on our world, depending on who you listen to. So what is it? And why is it such an important issue? Fracking (hydraulic fracturing) is a feat of engineering aimed to increase the yield of natural gas gleaned from the earth, in order to be used as fuel. As a fossil fuel, formed when marine plankton and ancient plants trapped sunlight energy and carbon over millions of years, natural gas is an unsustainable energy source and burning it produces carbon dioxide. Drills dig deep into the earth, vertically then horizontally, while pumping in water and chemicals at high pressures to open up fissures in the shale rocks way down deep: this frees trapped gases. These are then captured and piped off at the earth’s surface, ready to use as fuel (helpful video: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-23320540.) Having been widely used across the US, the government has recently announced the lifting of a temporary ban of fracking throughout the UK which has sparked controversy and protests, such as those in Balcombe and elsewhere. Why the enthusiasm? Hard to reach oil and gas can be accessed by fracking. It has been estimated that there is as much as 1,300 trillion cubic feet of shale gas underneath the UK – a tenth of which, if extracted, would be the equivalent of 51 years’ gas supply. (1) There are two main possible benefits: first, UK gas prices could be driven down, as they have been in the US. This could be a big boost in the days of our troubled economy, where many families struggle with meeting the rising cost of energy bills – but as this letter to the FT from a senior (republished here) explains, even using very optimistic assumptions only investors in the extraction companies and the Exchequer are likely to benefit, unless gas imports are penalised. At the same time, the cost of solar panels has dropped 80% due to a surge in Chinese production. Is it really just a coincidence that Osborne’s father-in-law is an oil and gas lobbyist?  From an environmental perspective, electricity can be generated from natural gas at half the CO2 emissions of coal (potentially at least) so, compared to coal it could plausibly be a step in the right direction. But there are big question marks on wheter this is true – see below – and is coal really the benchmark we should be using in 2013? Another potential benefit of fracking – especially in the context of today’s record unemployment - is the creation of jobs in Britain. David Cameron claims that as many as 74,000 jobs could be supported by the growth of this industry (1). If true, this would be hard to overlook, although many of them would be temporary. But the job creation argument applies just as strongly to investment in the green economy, as the Green Is Working campaign and this report from the Green Alliance show. Even if realised, the benefits of fracking come with big risks, and could cause lasting damage to our planet and our health. Water usage and chemical contamination Fracking uses huge amounts of water – just one site requires millions of gallons of water. This will compete with water resources in areas which are already prone to and experiencing shortages, areas which are also expected to increase with climate change. Transport of these large volumes of water to and from fracking sites will also have environmental impacts. In addition, there is serious public health concern about the risk of water quality being affected, with a concern that carcinogenic chemicals such as benzene, toluene, xylene etc among many others, used in the water will leak and contaminate groundwater around the site. Earthquakes There are concerns that fracking can cause earth tremors. In 2011, two small earthquakes occurred in Blackpool following exploratory fracking. Several reports have been conducted into the matter and it remains possible that future fracking will lead to some tremors. However, a recent report from the Department for Energy and Climate Change claimed that the risks of structural damage from these tremors remain low, and the process has been given the green light, albeit with stringent regulations.  Climate change The science is telling us that we really need to keep most remaining fossil fuels in the Earth if we want to avoid catastrophic climate change, as highlighted by Bill McKibben's Do The Math talk (coming to the UK this Autumn in a 'Fossil Free' tour coordinated by People and Planet!) In that context, is fracking just a distraction from developing renewable sources of energy? Cameron, like Osborne, says ‘we’re not turning our back on low carbon energy’ - just using fracking to help meet our energy needs – but we could do that with sustainable energy too. Does the move just encourage continued dependence on fossil fuels, ‘one last fix’ before we change? As Friends of the Earth’s Head of Campaigns, Andrew Pendleton, said in reaction to the 2013 Budget: "This is yet another fossil-fuelled Budget.... Our economy desperately needs new ideas, but George Osborne is a 19th century Chancellor, using 20th century tools to fix 21st century problems". Natural gas is mostly methane – which is over 20 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 – and it has been found to leak from fracking sites in quantities much larger than originally thought. Burning fracked natural gas is only a greener alternative to coal burning so long as gas leakages into the environment are kept to a minimum, specifically below 2%. Studies predict, however, that leakages may be significantly higher, with a recent study in Utah finding a leakage rate of 9%. A New Scientist article published yesterday cites that if rates are around 10%, at the top end of estimates for the US, then the escaped gas would increase global warming until the mid 22nd century. The climate is a very complex thing: the same article also notes that side-products of burning coal, sulphur dioxide and black carbon, actually cool the climate to some degree and offset some of the warming created by the production of greenhouse gases – although they also have negative health effects. There’s a lot to consider when it comes to the debate about fracking. What damage to our planet is too much? Will fracking really be the solve-all economic miracle the government is claiming? The debate is open – what do you think?  Isobel Braithwaite Also published in Stakeholder Forum's Outreach Magazine for COP18 Possibly the biggest problem we face now as a globe is how to cut carbon as fast as possible. That will require massive scaling up of renewables and scaling down of fossil fuel usage. As PwC recently reported, without unprecedented carbon intensity reductions, we are probably heading for a 6 degree rise by 2100. That will be much harder to avoid if we seek to end nuclear power. It is extremely low carbon, much cheaper than renewables, and the risks to health are much smaller than most people think. It could give us the time we need to carry out research in order to improve the efficiency and economic viability of renewables; increase their working lifetimes; and, crucially, to develop adequate storage capacity, which is essential given how intermittent they are. As James Lovelock, one of the world’s most highly respected climate scientists, explains, “opposition … is based on irrational fear fed by Hollywood-style fiction, the green lobbies and the media.” The prominent and well-respected environmentalists Mark Lynas and George Monbiot have also publicly explained their pro-nuclear positions, and the reasons make sense. So I was quite disconcerted earlier this year when talking to German young people overjoyed at their anti-nuclear movement’s political success in the wake of Fukushima. The result will probably be a doubling of the coal-fired power stations Germany will build over the next ten years: not the sort of change we can afford to be making now. The people I met had been acting in good faith – but it’s a shame if that idealism is ill-informed, when we so urgently need to be pragmatic. Nuclear has by far the lowest number of deaths per unit of energy generated, from accidents or air pollution, compared to any fossil fuel or biomass. Chernobyl caused 28 deaths from acute radiation sickness, and the WHO’s Expert Group’s Report concluded that over the long term the statistics suggest an 4000 additional cancer deaths among the 626000 people in the three highest exposed groups, less than 1/20th the baseline cancer rate. Fukushima has been predicted to contribute to approximately 100 early deaths from cancer in the long term but so far none have been recorded. Both are tragic: of course we must avoid future Chernobyls, but other much bigger health risks receive only a fraction of the attention. 19 205 life-years were lost per million in China due to air pollution from electricity production, in 2010 alone, whilst every year indoor air pollution kills almost 2 million people (2004 figure). In a 2007 article on electricity generation and health published in the Lancet journal, Markandya and Wilkinson conclude that nuclear power ‘has one of the lowest levels of greenhouse-gas emissions per unit power production and one of the smallest levels of direct health effects … it would add a substantial further barrier to the achievement of urgent reductions in greenhouse gases if the current 17% of world electricity generation from nuclear power were allowed to decline.’  Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, 2007 What about waste? CO2 tends not to be thought of as hazardous waste, but it certainly poses a severe threat to the health of future generations. Even renewables like solar have their problems, and a push for more biomass could spell ecological (and climate) disaster. With nuclear, as with climate, ‘doing the math’ is key: a typical background level of exposure is 2-3 milliSieverts/year, of which approx. 0.4mSv naturally occurs in food such as bananas. Regulations limit extra exposure from man-made radiation (other than medicine) to 1 mSv/y for members of the public, and most are exposed to far less. For comparison, the radioactivity of a single banana (the 'Banana Equivalent Dose'), due to the potassium it contains, is about 0.3mSv. Most of us are exposed to far more in our own homes due to naturally occurring radon gas: 2.7mSv/year for the average person in the UK according to the HPA; some people have much higher levels of exposure. I'm not pretending there aren't risks if multiple safety procedures are violated as at Chernobyl or plants are sited in dangerous places as at Fukushima, but good governance and well-chosen sites are both essential and possible; fear should not prevent us from using nuclear as a bridging technology. George Monbiot summarises the unavoidable trade-off around renewables: ‘we could meet all our electricity needs through renewables. But it would take longer and cost more”. The trouble with climate change is precisely that: we’re fast running out of time. Work by the Committee on Climate Change shows that the maximum likely contribution to UK electricity from renewables by 2030 is 45%; the maximum from CCS 15% - and the gap must be made up. In the short term, nuclear seems to me a far better way to fill that gap, for climate and for health, than fossil fuels. Izzy Braithwaite  Image courtesy of tcktcktck He may not have achieved much on the climate front in his first term in office, but unlike Mitt Romney, Obama does at least seem to understand the extent of the threat posed by climate change. And - although constrained by the Senate and political will on the ground - he is likely to make more progress on emissions reductions or at least have a better chance of it than Romney. But at the same time, PwC's recent report argues that we are on course for a catastrophic 6C rise by 2100 without urgent measures, and finds that we need deep reductions in carbon intensity of 5.1% per year to 2050 - over six times greater than the 0.8 per cent average annual cuts achieved since 2000 - to avoid dangerous climate change. Such cuts will be a real challenge for even the most committed nations and the US - whether under Romn. And all the while, fossil fuel companies such as ExxonMobil are funding pseudoscience that will help to keep the public in a state of doubt and confusion for some years longer so their profits aren't compromised. The libertarian US Cato Institut based in Washington, DC, recently published its new report, Addendum: Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States - and it is designed to look just like the U.S. government’s official 2009 National Climate Assessment:  This was presented to Congress in 2009 as the federal government's best single evaluation of the science and potential impacts of climate change. Eleven authors of the original government report wrote a recent letter protesting what they called the “deceptive and misleading” Cato report: “The Cato report is in no way an addendum to our 2009 report. It is not an update, explanation, or supplement by the authors of the original report. Rather, it is a completely separate document lacking rigorous scientific analysis and review.” The Union of Concerned Scientists' 2007 report, Smoke, Mirrors, and Hot Air, detailed ExxonMobil’s campaign to use front groups to fund misinformation about climate change. They documented that Michaels was affiliated with no fewer than eleven groups funded by ExxonMobil. Two of the six-member author team on this new Cato report were also highlighted in their 2007 report - Robert Balling was affiliated with no fewer than five “front groups” funded by ExxonMobil. See also DeSmogBlog for other great pieces of investigative journalism on how vested interests have clouded awareness of climate science and impacts - we need to know what we're up against, as they have plenty of money and for a number of the fossil fuel companies it's certainly not matched by their scruples. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed