Alistair Wardrope, Healthy Planet Sheffield Originally posted here Would anyone dispute that healthcare systems ought to put their patients first? The mantra has a near-unassailable status in discussions of the best foundations for healthcare. The UK’s General Medical Council makes it first amongst the Duties of a Doctor; it provides the title of the Department of Health’s response to the findings of the Francis Report; and it lies (in its more-theorised form, ‘patient-centred care’) at the core of Don Berwick’s recent report into safety in the NHS. No politician, of any political stripe, would see fit to enter into a debate on health without it taking pride of place in their rhetoric. I’ve used it myself, campaigning for the priority of “patients before profits”. Nonetheless, I’ve long had qualms about it. It took a work of fantasy to figure out exactly why. During a recent and all-too-brief summer break, I decided to read China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station. I had harboured the vague intent of doing so for several years, but a fortuitous alignment of stars and an inability to access the books I was supposed to read in the university library meant I finally did. As a (somewhat lapsed) devotee of speculative fiction, I’d always expected to find more than simple escapism between its covers; however, I did not expect it to form the nucleus around which those nagging worries about patient-centred care would crystallise. The passage that set me thinking is little more than an aside, one of the short conversational detours the novel is littered with. It concerns a society of nomadic bird-people, the Garuda of Cymek. Garuda society is founded on the moral and political primacy of individual freedom. Their legal code admits but one crime – depriving another Garuda of choice; their ethical code, only one vice – disrespect. So far, so Tea Party. But the Garuda take these principles in an altogether different direction. Their interpretation of individualism rests on a particular understanding of what the individual is: the ‘concrete’ individual. As Ged, the autodidact librarian-priest, states: You are an individual inasmuch as you exist in a social matrix of others who respect your individuality and your right to make choices. That’s concrete individuality: an individuality that recognizes that it owes its existence to a kind of communal respect on the part of all the other individualities, and that it had better therefore respect them similarly. With the individual understood in these terms, disrespect becomes at heart a crime of ‘abstraction’: isolating one’s own individuality from the network of social interactions by which it and other persons are constituted and so losing the symmetry between them in which equal status is grounded. The Garuda share their ‘concrete’ understanding of the individual with a strong line of philosophers and political theorists. In his influential essay ‘Atomism’, the communitarian thinker Charles Taylor describes the individual as existing only when grounded in a society that affords the material, psychological and social resources for them to develop into freely-choosing agents, and provides the range of options necessary to make such choices meaningful. Respect for such individuals, therefore, is inseparable from respect for the social conditions underpinning their individuality. This is in stark contrast to the ‘atomism’ of the title, a charge he levels against the libertarian individual, whose values and preferences are interpreted and realised independently of others, and the protection of whose choices sets the boundaries of an acceptable social contract. These ideas are developed upon in recent work in feminist philosophy on ‘relational’ conceptions of autonomy. Traditionally, medical ethics has employed a rather thin understanding of autonomy – interpreted in the doctrine of informed consent, for example, as little more than decision-making capacity. Relational theorists argue that this ignores the role played by our emotions and attitudes towards ourselves and others – and their attitudes towards us – in developing and maintaining our capacities for autonomy. Consider an individual who, after a lifetime of oppression, comes to adopt those oppressive values as his own; the individual who does not have the necessary self-respect to consider herself worthy to make her own; or the individual who, like Aesop’s fox rejecting the inaccessible grapes as sour, comes to view certain ways of living as undesirable only because they are not realistic options available to them. In each case, the individual may be in full possession of the faculties that constitute mental capacity, but faces more subtle, relational, threats to their autonomy. The concrete individualism of the Garuda – and the work of communitarian and relational theorists – captures my concerns about patient-centred care. For in many interpretations of the term, the idea of the patient upon whom care is being centred is what the Garuda would consider an abstract individual. When patient-centredness merely means enhancing patient choice, increasing medical consumerism or a way to promote marketisation of health services, we present the patient as the isolated, rational ‘chooser’ that is the subject of Taylor’s ‘atomism’ critique. More generally, an interpretation of patient-centred care focussed solely on the clinical encounter – where it concerns only the interactions between health professionals and the individuals who come to them at the point of clinical need – risks leaving out other individuals and important aspects of care. When care is centred on the patient, who or what falls into the periphery? It seems to me that many who fall into the margins of this picture are those who are already most marginalised. Most obviously entering into this group are those who need health care but are unable to access it: ‘patient-centred’ care, focused on the abstract patient, has nothing to say about caring for those who – through legal, economic, social or psychological barriers to access – are unable even to become patients. But, even setting aside the tremendous injustice and inequity – where the most vulnerable communities, such as vulnerable migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, poor and oppressed groups, are done further harm –ignoring these groups is a public health disaster. Perhaps this could be remedied by defining ‘patients’ according to their need for health care rather than their ability to access it; but this picture still sees those patients as abstract individuals, and so has little room for public and global health concerns that make no sense in individualistic terms. Infection control, mitigation of climate change and its health impacts, social and political action on the social determinants of health: all are relational public goods. They are not focussed toward, or done in aid of, any individual patient, and only make sense at a population level. In the current political climate in the UK – where attempts are being made to limit access to healthcare for migrants, and such care is increasingly conceived of as a service provided to individuals for individual benefit – the rhetorical use of patient-centredness emphasises only the abstract patient, with the attendant dangers to public health sketched above. But the good news is that, when the individual is understood in concrete terms, these dangers are not just brought back into the fold – they become a central component of patient-centred care. The reason why is simple: the health of the individual simply cannot be considered in isolation from that of the population. As Sir Muir Gray writes, “personalised and population medicine are interwoven like warp and woof.” A healthcare intervention is never solely for a single, isolated patient; it is simultaneously a public health measure. So when the International Association of Patient Organisations puts patient involvement in social policy, universal access to health care, and attention to education, employment and family issues at the core of its definition of patient-centred care, it is not adding these in as an additional ingredient to aiding execution of the interests and desires of individual patients in the clinical setting. Rather, it acknowledges the former as a core component of the latter. And protecting and extending access to healthcare for migrants – economic, asylum seeker or undocumented – is not a good to be weighed against the health needs of a nation’s citizens, but an integral part of serving those needs. In meeting the challenges of shaping more environmentally sustainable health systems – able to meet the needs of people today without sacrificing those of future generations – we need not marginalise or ignore current patient’s interests; as elsewhere in healthcare improvement, “the greatest untapped resource in healthcare is the patient.” Such work on sustainable healthcare – the focus of this September’s CleanMed Europe conference in Oxford – is a re-interpretation of what patient-centred care could be, modelled on a more comprehensive understanding of what it means to be a patient. It turns out, then, that my concern is not primarily with putting patients first, or with patient-centred care – at least, not with what those ideals could and should mean. The problems arise only when the individual is considered in isolation from their social and political context and the environment around them. Given the fundamentally relational nature of health and disease, this isolation is intellectually and ethically untenable; patient-centred care makes sense only when we listen to the lesson I was taught by a fictional society – to view patients (ourselves included) as concrete, inherently social, individuals.

0 Comments

Izzy Braithwaite From a BMJ Blogs series for the upcoming CleanMed Europe Conference - edited version at: http://bit.ly/13EBL8D The concept of sustainable healthcare and – related to that - how environmental change affects health are not generally taught in medical schools, but I was lucky enough to take part in a student-led national programme on the topic in my first year. I had long been interested in global health and the environment, so was keen to find out more and get involved in this area. The focus of my work has been with the Sustainable Healthcare Education (SHE) Network, for example contributing to a set of downloadable teaching resources and subsequently helping to collate a set of case studies on existing student-selected components. I’ve also been involved in the most recent project on curriculum learning outcomes, organised in response to a request from the GMC, which has been a multi-stage consultation process. The three overarching learning outcomes proposed on the basis of the consultation are to be published online soon and cover: the relationship between the environment and health; the environmental sustainability of health systems; and the ethical and policy-related issues that arise from understanding these two topics, such as how the duty of a doctor to protect health applies to future generations. As I‘ve read more about our impacts on the environment, climate science and the extent to which human health depends on ecosystems and climate stability, I’ve been surprised and concerned by how little of this information seems to reach the general public, including medical students. To help change that, I’ve been running workshops and campaigns with a student group called Healthy Planet UK, in partnership with a larger network called Medsin. Medical educators, students and clinicians wishing to set up more teaching in their medical school often encounter objections that there's not enough space in the curriculum or that these topics aren't relevant. Yet the evidence shows that climate change is an increasingly important threat to global public health, and I think the scope for health professionals to help shift political narratives around environmental issues is often underestimated. If my cohort of future doctors needs to know about tobacco or antibiotic resistance, then surely we also need to understand how changes to weather patterns and ecosystems are affecting, and predicted to affect, health. Equally importantly, we need to be aware of the growing evidence base around the opportunities, termed 'co-benefits', to deal with burgeoning public health problems such as obesity and poor mental health in a way that's synergistic with the goals of sustainable development. Given some of the details I had to learn in pre-clinical medicine, the argument that there's not enough space in the curriculum suggests it’s an issue of priorities. Do we really think enabling tomorrow's doctors to tackle what may well be a bigger health threat than tobacco - especially considering the complete inadequacy of the political response so far - matters less than learning, for example, all the steps of the Krebs cycle? My learning in this area has influenced the way I think about the rest of my education, and I think I'll be a better doctor for it; better able to understand the macro-scale influences on patients' lives, and to contribute to discussions about how health services could be better for both patients and the environment. To create lasting change - whether in sustainable healthcare, climate policy or other public health issues – tomorrow’s doctors require an understanding of the issues, to have had the freedom to discuss them and try out their ideas, and the skills for effective collaboration, including inter-sectorally. Through the SHE network, we are seeking to create this space for students to learn, reflect and debate about the issues, and to develop the skills to help lead the transition to sustainable healthcare. The fourth CleanMed Europe conference takes place at the Oxford Examination Schools from 17th-19th September, and Izzy will be talking about the SHE Network and Healthy Planet's activities during the conference. Shuo Zhang

I recently attended Healthy Planet's panel discussion with Professors Hugh Montgomery, Ian Roberts, Anthony Costello and David Satterthwaite during the climate talks. They have all had long and varied careers, but their interests have converged in recent years by a deep motivation to advocate for urgent action on climate change. What really struck me during their presentations, and the subsequent question and answer session, is how far the climate change and health movement has come since the UCL-Lancet Commission in 2008, and also the diversity of perspectives, approaches and forms of engagement on the issues. During these past four years, arguments have been redefined, emphasis redirected, and the movement has taken on board some important new evidence. Past motivations First, a quick history of how the climate change and health movement has gathered momentum. In 2007 Climate and Health Council formed as ‘a meeting of doctors, nurses and other health professionals recognising the urgent need to address climate change to protect health’. In 2008, Anthony Costello led The Lancet commission framed Climate Change as the ‘biggest health threat in the 21st century’ and set forth an interdisciplinary research directive to clarify and quantify the potential magnitude of climate change's direct and indirect health impacts. Impacts such as heat waves, changes in vector disease, air pollution and broader economic and geopolitical instability. The Campaign for Greener Healthcare, now named the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, was set up at the same time to develop a range of projects and programmes which focused on engagement, knowledge sharing, and transformation of the health system. In April of the same year, the NHS Sustainable Development Unit was established to ‘help the NHS fulfil its potential as a leading sustainable and low carbon healthcare service'. They state that they do this by 'developing organisations, people, tools, policy and research which will enable the NHS to promote sustainable development and mitigate climate change'. These strands of global health, NHS sustainability and interest in transformative healthcare came together in 2009 with an organised and coherent health message at The Wave march before COP15 in Copenhagen – that 'what’s good for the climate is good for health'. These strands still very much underlie and motivate the work that is being done, however both the political and economic landscape have changed. There is a new urgency - since the initial Lancet Commission in 2008, new evidence now confirms some previously uncertain climate change impacts - however with the current economic recession, it seems there is less political will and public interest in the topic. Why do we still care? Perspective from the panel came from both personal and professional motivations. Prof Hugh Montgomery articulated the interconnected social, geopolitical and economic impacts on vulnerable populations in the developed and developing world of the indirect impacts of climate change today. This was most keenly illustrated through the impact of global weather on grain harvests, food prices and acting as a contributing factor to the Arab Spring. Resource insecurity further compounds the pressures of future population growth on an already struggling planet. These themes of population, gender empowerment, new technologies, carbon-co benefits, have been consolidated within a development discourse and further, within an intergenerational justice discourse. Prof Anthony Costello presented updated research on the direct health impacts of climate change in terms of disease modelling. It’s not just about future global impacts either. Prof Ian Roberts articulated the difference between demanding action to mitigate against the impacts of carbon on health, and demanding action on the negative health effects of carbon now. Focusing on active travel in particular, he showed the potential benefits of reducing our reliance on the car and embedding active travel in our lifestyles, cities and communities. And not just because it's healthier or lower carbon - but also because it can be more enjoyable. This is applicable across the board: decarbonising our lifestyles re-emphasising meaning over consumption can help us to have healthier bodies and nicer places to live. Prof. Satterthwaite stressed that we mustn't forget that vast populations still live on the edges. They build homes and communities in the high risk peripheries of cities as cities are where today's economic opportunities lie. These incredibly vulnerable settlements need adaptation to the impacts of climate change now, but they are often the least able to vocalise their needs and participate in local governance. So what is needed for the future? Some questions that I feel still need to be answered: should emphasis be on top-down action and policies or bottom-up capacity building? Can city and community level organisations be a new centre of power? How do we make sure that money and support gets to the people who need it most? And how can we ultimately make the most difference? Fundamentally we all need to change what we are doing now, and to make better plans for the future. I feel that healthcare professionals still have a lot to offer - we have a duty of care morally for our patients, and to minimise the impact of our healthcare systems on the planet, since it in turn sustains health. Moreover, healthcare professionals interact with all sectors of society, have a global outreach and from the already existing healthcare partnerships and projects already set up, there is a pre-existing infrastructure there to disseminate information and create change. Shuo Zhang The conference of youth has already begun in Durban and the actual Conference of the Parties will be kicking off on Monday. I am both very excited and also a little bit concerned. I am excited because I feel that this year the Medsin delegation has put in so much work on framing our message and in understanding the negotiation process and the various audiences we want to target, that even though I won’t be going to join them, I know that they will all do their best to make the health message be heard.

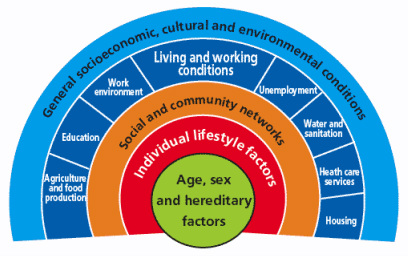

What I am a little bit concerned by is how the media is going to cover the conference- would very little coverage be preferable to coverage of in fighting and walkouts? How much of the content of the negotiations, as opposed to the dramas will be covered? And something perhaps a little bit more philosophical- is it good that climate change has turned from being news-worthy to being something that is more in the features pages... Most of these worries are a bit excessive, and probably mainly to do with the fact that I won’t be in Durban to throw myself into the work, so instead I will be scouring the media keenly here to keep an eye on how things get translated. However I have been thinking, and realised that sometimes lack of media coverage can perhaps be a good thing. It is easy to get caught up with the negotiations, but what is really important is the long term work on personal, institutional and wider societal change that really matters. Durban is a good spring board to encourage action and enthusiasm and offers a time and place to take stock, however what is really important is for us to let people know about the wonderful work that the already being done. And as healthcare professional we have already been doing a lot, and we have the capacity to do a lot more; we just need to incorporate sustainability into our everyday practice and clinical thinking and make use of the partnerships that are available to us. And as medical students we are in the right place to make these changes, whether through asking climate change and health to be included as part of our curricular, doing projects and SSCs on the subject, and even just asking the consultants who teach us about their own clinical practice, and how they can make it better. So even if we don’t get the media exposure we wanted from the Durban conference, there’s still a lot of very important work to be getting on with! Below are just a few links to the work that the UK health community is already doing well: http://sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/green-nephrology-programme : Spearhead clinical programme that aims to look at how to make renal medicine and dialysis more sustainable http://www.nottenergy.com : A local government and NHS trust partnership that aims to address health inequalities, by working on fuel poverty. http://www.bluegym.org.uk : Community and university project that aims to look at how our coasts can be used for health benefits By Shuo Zhang  Dahlgren and Whitehead model (1991) of the determinants of health [6] First published in 'Art of the Possible - the Cambridge Journal of Politics' 2011-02-13 2010 saw a year of spending cuts, riots about public sector reforms and a shift in rhetoric away from “big government” to “big society”. Fundamentally, according to the Coalition Government’s vision, the state needs to move towards leaner, meaner public services and greater freedom and individual choice. This social, institutional and political change has implications for the National Health Service (NHS) in direct and indirect ways, both as a result of the 2010 Health White Paper1 and through the impact on other services that influence wider social determinants of health. Doctors have had a mixed reaction to the new ideas, getting caught up in enticing vocabularysuch as choice and power. However, most have concerns about the risks associated with implementation. The profession faces many challenges in the years to come, not only due to changes in the demography of disease, but also changes in pensions, employment rights and training, technological and scientific innovations, and new emphasis on sustainable practice and preventative medicine. So how has the new Coalition Government approached health and will it meet the challenges for the future? Healthcare is assumed to be a pillar of society and, even in this climate of austerity, the Coalition is keen to be seen to protect the NHS. The 2010 White Paper promises real-term increases in funding, although it also stipulates the need to move towards greater efficiency and cost savings of £20 billion in the next few years. Beyond the economics, the new Health White Paper advocates structural institutional change and a shift in power towards patients and frontline professionals. In addition, public health is to become more integrated with local councils. These proposals have underlined tensions and contradictions that touch upon wider political debates about how the country should navigate this period of hardship.2 One of the most significant proposals is the introduction of the GP-led commissioning service and greater choice for patients when registering with providers. This aims to move control away from managers and towards people who know and use the system the most. This has parallels with existing patient-led support services and health activism that has broadened the health service into a user-provider network, replacing previous patriarchal structures. As an idea, a new directive that empowers patients should be welcomed; it allows them to take their health into their own hands, and could produce a system that is pro-health instead of anti-ill health. In practice, however, the implementation of these proposals may have unintended effects, such as changing the dynamics of the patient-doctor relationship, diverting more time away from patient care due to increases in paperwork and leaving the back door open for potential privatisation. This patient empowerment may also be too far down the line, and only after bad lifestyle choices have already been made, to make much difference to prevention. Furthermore, choice is often just a buzz word for the middle classes, and by creating a system whichpriorities the most vocal needs, hidden inequalities in access and treatment may emerge. A change that perhaps makes more sense is the reconstitution of public health to local authorities. This moves the remit of action for local authorities further up the chain and gives them a greater role in co-ordinating approaches across diverse sectors such as transport and education.3 In effect, it replicates approaches to public health from Victorian England when it formed a central part of town planning. This move will give the medical profession greater powers to address broader social determinants of health, but may also leave it more exposed to criticisms of state ‘nannying’. The government has also failed to consider the continuity of public health in both a community and clinical setting. Public health in clinical practice is vital in providing evidence and improving practice. Moving responsibility for aspects of public health to local councils may create discontinuity and compromise broader goals. The ring-fencing of public health funding under the Coalition signals their intention to continue to address inequalities in access and care; however, this contradicts the cuts to departments in key peripheral areas such as social care and education. To carry on business as usual is not an option. However, the proposed changes were not part of a natural evolution based around principles of adaptation and mitigation, but more of a reactionary event to a system already perturbed. The Coalition’s vision lacks coherence, and there are other ways forward in which power could be better balanced between organizations and individuals. The perspective I have gained from being involved with the climate change and health movement is one of pushing forward change and alternatives to the big picture in a subtle way: changing the way we think about health systems and social structure, changing our behaviour, and seeing savings in efficiency as opportunities rather than cuts.4 It is also a direction which embodies the ethos of ‘prosperity without growth’5 and is careful of the wider political and socio-determinants of health6. The movement realised that it had to re-frame climate change as simply an evolution for the better. For example, infrastructural and efficiency changes will have direct financial savings, with a reduction in emissions as an added bonus. On a personal level, eating less red meat and dairy products, and cycling more will have a primary health benefit as well as positive environmental impacts. In a way, we were trying to change people’s behaviour and thoughts without loading it with values and ideology. Big and, more importantly, sustainable differences can be made if small changes in perspective occur across the board. Ultimately, the danger is that the Coalition Government’s changes are ideologically driven instead of evidence-based. For these changes to be unleashed on an organization that employs 10 per cent of Britain’s workforce without initial trialling is a huge risk. If these structural changes do come into effect it will impact upon fundamental relationships between science, policy and the public. These spheres of influence, which are illustrated by figure 1, extend across individual, group and societal levels. The Coalition should be more aware of these connections. Have they done enough to ensure healthcare will be fit for the future or should we too be protesting for a new way forward? References 1 Department of Health, Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS - Health White Paper 2010, London: The Stationery Office, 2010. 2 British Medical Journal, “More brickbats than bouquets?”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c3977. 3 Anthony Kessel and Andy Haines,“What the white paper might mean for public health”, British Medical Journal, 341 (2010): c6623. 4 Muir Gray and Frances Mortimer, “Transforming Clinical Practice”, Sustainability for health: An evidence base for action, 2 December 2009. http://www.sustainabilityforhealth.org/clinicaltransformation/opinion-pieces/transforming-clinical-practice, accessed 10 January 2011. 5 Tim Jackson 'Prosperity without Growth' (2009) Routledge ISBN-10: 1849713235 http://www.amazon.co.uk/Prosperity-without-Growth-Economics-Finite/dp/1849713235 6 G Dahlgren, M Whitehead 'Policies and strategies to promote equity in health' (1991) World Health Organization. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74737/E89383.pdf |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed