|

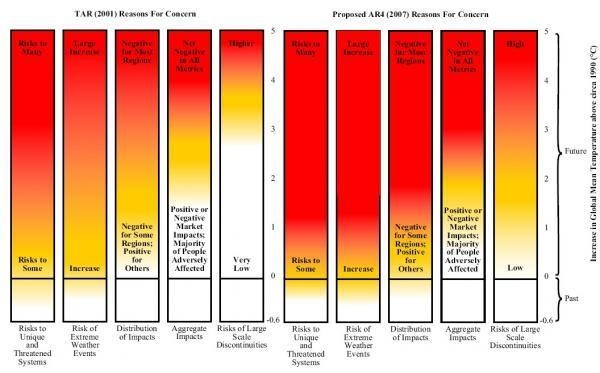

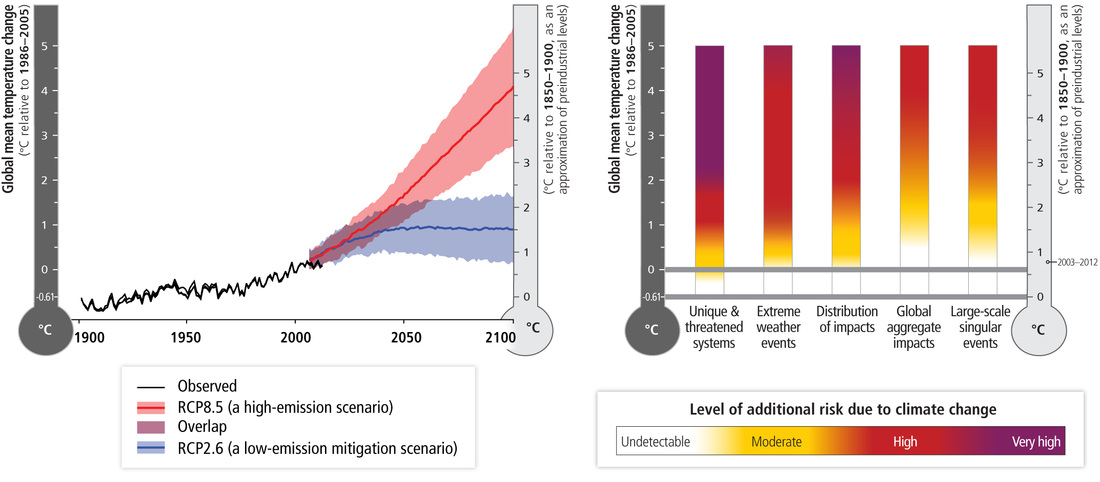

Healthy Planet were in London this weekend for a maximal-efficiency climate and health double-bill: the Medsin 2015 Global Health Conference, and the ‘Time to Act!’ national climate march. We like to take our beard-stroking with a healthy dose of actually doing stuff, and London offered us ample opportunity for both. The theme of the GHC, organised and hosted by UCL Medsin, was ‘The Bottom Line’ – one particularly relevant for HP’s recent work on fossil fuel divestment, given detractors’ concerns about the impact of taking action on their bottom line. Moreover, climate change itself poses the ultimate bottom line – the boundary of a planet no longer capable of supporting a healthy society. Nationally and internationally, this boundary has been quantified in terms of the 2C surface warming goal – the bottom line to which all climate mitigation policy is supposed to add up. But the cultural currency of this simple proposition – that global mean surface temperature increase should be constrained to within 2C warming relative to pre-industrial times – belies the complexity of the underlying science, and the health threats posed by climate change. Three questions immediately suggest themselves. Firstly, why – of all temperatures – pick 2C? Secondly, what do we neglect by making this goal the focus on climate mitigation efforts? And lastly, what do we need to do to achieve it? For all of its dominance in contemporary climate policy, the history of 2C as the limit of ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference’ hardly offers conclusive reasons for its adoption. It came about rather from the efforts of a group of German climate scientists to find a hook that would make the esoteric scientific debates accessible to a policy audience, and motivate substantive action. To do this, they sought a single parameter, and a ‘safe’ limit to that parameter for global society. Surface temperature provided a natural parameterisation, given its close association to the natural and human impacts of climate change. As for the boundary, a helpful demonstration of the motivations is offered in the IPCC’s ‘ember diagrams’ of reasons for concern shown below – the Third Assessment Report (TAR) version shows that, at that time, 2C warming was thought to keep the risks of overall global aggregate impacts (chiefly measured by economic and human costs) low. It was also thought that, at such levels, the risks would remain low of bypassing ‘tipping points’ – step-changes in the natural environment that – like the West Antarctic or Greenland ice sheet collapse – would suddenly and irreversibly alter the climate, or – like seafloor or Arctic permafrost methane release – result in positive feedbacks that would ‘lock in’ further warming independently of human carbon emissions.

But if the 2C goal focuses on global aggregate impacts and tipping points, what does it neglect? Some clues to this are also displayed in the successive ember diagrams. An omnipresent and purely formal difficulty arising from using marginal benefits to determine goals is that such goals will neglect the distribution of those benefits. And, as the embers show, even if at 2C the human cost of climate change to some may be offset by economic benefits to others, the differences between who benefits and who pays are striking. It is well established that those least responsible for climate change are, in general, those who suffer most, and climate change acts as an intensifier for many existing inequalities. This is most strikingly demonstrated in the risks of warming to ‘unique and threatened systems’ – communities and ecosystems that may be lost altogether thanks to climate change. While the ‘global aggregate impacts’ of 2C warming may be manageable, a world that much warmer is one in which many unique ecosystems – coral reefs, or amphibian habitats – may be lost altogether, while some societies – Inuit communities and pacific islanders – will see their way of life melt away, or disappear beneath the waves. One might, therefore, be led to question whether 2C is an appropriate target, given how the science of climate change has developed since its proposal and the normative framework used to arrive at it in the first place. But further, one could question whether surface warming – or surface warming alone – is the appropriate parameter to be targeting at all. A high-profile editorial in Nature last October raised precisely this question, suggesting that instead a host of planetary ‘vital signs’ should be considered to map the differential impacts in different regions and on different systems of a changing climate. While some questioned the scientific validity of their suggested alternatives, and others endorsed the pragmatic value of the 2C target, the critique gained traction perhaps because it highlighted the shortcomings of one of the few relatively uncontroversial propositions in climate policy. But, even if one were to find a perfect way of measuring climate change, would setting our targets in terms of climate change alone be adequate? For, as Christina Figueres (secretary of the UNFCCC) has said, climate change is not a disease; rather, it is a symptom, and only by looking at other associated symptoms can one come to an accurate diagnosis. A host of other planetary boundaries – biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, land use change to name a few – are affected by the same social, economic and political processes driving climate change. Many of these are in fact taken into account in international climate negotiations – but to look at surface temperature warming alone neglects some major associated threats to human and planetary health. For all its shortcomings, however, 2C has one major advantage; it’s catchy. It expresses a simple, accessible objective, one that both demands immediate action while still being achievable. And as an explicit commitment of most governments worldwide, its implications for the need for rapid decarbonisation if we are to stay within a 2C carbon budget gives it potent campaigning value. Few propositions could win equal support from climate activists and the governor of the Bank of England. It’s this cultural currency that has made the fossil fuel divestment campaign the fasting-growing of its kind in history. For more on the advocacy and activism that has grown around this bottom line, see our next blog…

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed