Motion 370, which is to be debated at the Annual Representatives’ Meeting (ARM) of the British Medical Association (BMA) tomorrow morning, calls on the BMA to ‘transfer their investments from energy companies whose primary business relies upon fossil fuels to those providing renewable energy sources’ in light of the health risks posed by climate change. This is, to my knowledge, the first time that a health sector organisation has publicly considered joining the growing international fossil fuel divestment movement. That it’s coming from the BMA, one of the oldest and most respected medical professionals’ organisations in the world, demonstrates the power of the divestment movement – one that has spread over the past couple of years from a handful of US university campuses, to encompass faith groups, pension funds, and government authorities across the globe – winning endorsements from such high-profile voices as Desmond Tutu, Christina Figueres and even Barack Obama along the way. And it’s working: the fossil fuel industry is scared, as demonstrated by the Australian coal lobby’s efforts to outlaw the campaign. There are plenty of good reasons, medical and financial alike, for the BMA to divest. The BMA’s values and objectives, and the responsibilities of the profession it represents, demand that it should act on “the greatest global health threat of the 21st century.” Continuing to invest in the fossil fuel industry is literally betting against action on climate change mitigation, given that the industry’s continued profitability is dependent on burning more carbon than the planet can take; while the transition to the low-carbon economy could bring huge health co-benefits, from reduced air pollution, healthier transport and diets, and improved urban and rural environments. The arguments for divestment are summarised in our two-page briefing written in advance of the motion. Chances are, though, that if you’re reading this then you’re already familiar with these arguments. I’d like to consider, instead, what it would mean for the divestment movement, and the future of the world’s energy economy, if the BMA were to divest. Some clues might be found in the BMA’s last high-profile divestment campaign – targeting the tobacco industry.

In 1985, the BMA published a report disclosing details of many prominent health institutions’ investments in tobacco at a time when their advocacy for tobacco control was increasingly vocal. A year later, the American Medical Association wrote to every US medical school calling for divestment from tobacco. Today, UK health institutions - from the medical Royal Colleges and BMA to the Wellcome Trust - screen investments in the tobacco industry from their portfolios as a matter of course. The health profession as a whole has unambiguously stated that public investment in the tobacco industry is unacceptable, a vested interest in an industry hazardous to human health. Though complex to evaluate, tobacco divestment is widely regarded to have been integral to the tobacco control movement’s successes. Since the BMA’s 1985 report, this has changed from almost ubiquitous access to and advertising of cigarettes, to the point where doctors can now even entertain the idea of making the sale of tobacco illegal. Could fossil fuel divestment contribute to a similar shift in social norms? The parallels between the tobacco and fossil fuel industries are many. First, their health impacts are comparable in scale. The most recent Global Burden of Disease report attributes 6.3 million avoidable deaths in 2010 to smoking; meanwhile, approximately 7 million were caused by air pollution and climate change is understood to pose one of this century’s greatest threats to health. Secondly, both industries are infamous for their roles in subverting scientific research and undermining human health to protect their profits. In a now-infamous internal memo, the tobacco company Brown and Williamson proclaimed, ‘Doubt is our product, since it is the best means of competing with the 'body of fact' that exists in the minds of the general public.’ Big Oil has been the primary heir to Big Tobacco’s playbook, using the same tactics – often even involving the same institutions and researchers – in their efforts to discredit climate science. ExxonMobil alone spent $27.4 million on such work from 1998 to 2012, in addition to the billions spent by the industry on lobbying governments worldwide to reject, weaken or undermine environmental legislation. If investment in the tobacco industry is incompatible with healthcare institutions’ objectives because of tobacco’s adverse health impacts, then the same logic – given the state of the science of climate change, and the many health co-benefits of sustainability – creates a clear moral imperative for their divestment from fossil fuels. And if the fossil fuel divestment campaign follows the course of the tobacco campaign, then the BMA’s support could contribute to a lasting shift in social norms and the entire political economy of our energy choices. If you think the BMA should divest tomorrow, then let the world know! Email your local representative; encourage your friends and colleagues do do similarly; talk about it on Twitter (use the hashtag #ARMlive); share the briefing. Tomorrow’s vote could be a pivotal moment in the health sector’s work to find solutions to the climate crisis – or it could see it continuing to fund the companies driving it and blocking legislation.

0 Comments

The plenary room in Bonn (from UNclimatechange on Flickr) The plenary room in Bonn (from UNclimatechange on Flickr) Gabriele Messori The United Nations’ climate negotiations usually gain the press spotlight once a year, when the big Conference of the Parties (COP) meeting takes place. However, the process of designing a global climate agreement is ongoing, and additional meetings are scheduled throughout the year. One such meeting is currently taking place in Bonn. The meeting addresses a broad range of topics, among which mitigation, adaptation, climate equity and climate finance. All of these are crucial for minimizing the social and economic impacts of climate change, and all can reduce the severe health footprint that a changing climate inevitably has. There is a wide consensus that time is running out and the meeting’s co-chair, Mr. Runge-Metzger, warned that if no decisive action is taken we could be looking at a 4 ˚C warming by the end of the century. This would spell catastrophe for the most vulnerable countries, such as small island states and least developed countries, Because of this, the least developed and developing countries are demanding that the developed countries step forward and take the lead, both in terms of national plans to reduce emissions and in providing climate finance. As eloquently stated by the Philippines, “In our delegation we do not speak of support... finance is a commitment by developed countries, not support.” In line with the feeling that the time is ripe for decisive action, it was decided to establish a formal negotiation group, called “contact group” in UN jargon, to continue the work on a global climate treaty. This decision will come into effect in June, when the parties will meet again to proceed with the negotiations. This is a distinct step forwards from the informal consultations that have taken place for the last two years. Besides this, however, the meeting in Bonn has had few concrete outcomes. The talks have been plagued by clashes over procedural and organizational issues, which have often overshadowed the central point of the negotiations, namely climate change. With time running out and the aim to have an ambitious global climate treaty in place by 2015, every second of negotiating time is precious. Today is the final day of meetings here in Bonn, and we all hope it will end on a positive note, preparing the ground for the next round of talks in June. Alistair Wardrope The climate crisis is, first and foremost, a crisis of over-consumption. This was one of the overriding themes of the ‘Global Health and Justice in a Changing Environment’ conference this weekend. This conference, organised by the UCL branch of Healthy Planet UK, looked at the intersection of environmental change, health and social justice. The speakers highlighted how intensifying patterns of unsustainable, resource-intensive and inequitable consumption are driving global environmental change. They also demonstrated that although the crisis is primarily about consumption does not, despite what some dominant paradigms would leave us to believe, mean the solutions are all in the hands of individual consumers. Consumption is a function of interwoven social, political and economic norms, and the conference showed that the transition to a more sustainable society demands collective action to restructure those norms. This observation should be familiar to anyone who has looked at the evidence on behaviour change in health promotion. In many nations in the global ‘North’, individualism dominates in health promotion - yet individualistic interventions have largely been unsuccessful. As Daniel Goldberg has highlighted, their benefits are frequently modest and short-lived, they exacerbate already-severe health inequalities, and – through ignoring the societal factors that influence patterns of disease - can increase stigmatisation of already-marginalised groups. This individualistic approach is neatly satirised in the Townsend Centre’s alternative to the UK Chief Medical Officer’s ‘Ten Tips for Better Health’:

The Townsend Centre’s Alternative Tips highlight the absurdity of prescriptions for individual behaviour change that ignore the social context. It is the social context which shapes people’s capacity to act upon such advice, and such prescriptions also ignore the direct influence that the social environment has on health. Yet our governments have embraced a similarly individualistic approach in looking at the changes required to combat climate change. DEFRA’s Pro-Environmental Behaviours Framework, for example, provides a set of 12 “headline behaviour goals”. Following the Townsend Centre’s example, the contributions of those present at the Healthy Planet conference this weekend provide us with ample information to revise this framework in a way that better understands the social context. Pro-environmental behaviours: an alternative framework DEFRA’s first behaviour goal looks at proper water resource stewardship, but a rather different dimension of water management was, unsurprisingly, more on the minds of those present at the conference – flooding. Andrew Watkinson and Mark Maslin highlighted how flooding embodies a recurrent pattern in the consequences of climate change – those least responsible are often those worst affected.

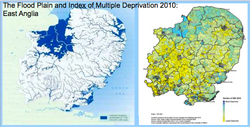

This applies not only internationally – 25% of Bangladesh being under threat from sea level rise, for example – but also within the UK; as Andrew Watkinson showed in a highly visual way (see images, left), the regions of East Anglia most threatened by flooding coincide neatly with those with the highest indices of multiple deprivation. While the distribution of these risks is to some extent about physical geography, our response to them is a matter of political will – and, as Watkinson further observed, the need for government intervention to compensate for flood damage and mitigate further flooding risks only started to move up the agenda when wealthy Thames Valley land and capital was threatened; similar discourse was notable only by its absence when flooding hit Hull and Sheffield. This is a profound injustice which we must not overlook. As Mala Rao and Ilan Kelman highlighted, there are many more dimensions than poverty alone when considering the social justice implications of climate-driven natural disasters, looking at the impact of gender on morbidity and mortality in flooding (where, for example, women and children are up to 14 times more likely to die than men, worldwide – although in some developed countries this pattern may be reversed, again due to gender stereotypes and different cultural expectations). Whose mobility, how?

Rachel Aldred left the conference in no doubt that transport was an issue of social justice. If one image alone could provide sufficient argument for that point, her photo of a Ryanair advert over a dangerous, unpleasant inner city highway (right) was it: a city designed for able-bodied, affluent car users, providing an alienating, intolerable lifestyle escapable only by cheap flights to sunnier shores. She also examined the relationship between gender and active travel in the UK, noting that our cities, where they cater to the preferences of cyclists at all, favour men’s perspectives on what makes cities fit for cycling. The ugly situation described by Dr. Aldred is in stark contrast to the potential benefits to be realised from embracing approaches to active travel that look first at the environment we create for it – Freiburg is a prominent example of what can be achieved when we look beyond the individual in trying to reduce our dependence on cars, instead creating cities that do not lead to such dependence. Energy & fuel poverty DEFRA’s goals do consider the importance of approaching energy production and consumption for tackling climate change, but entirely neglect the obstacles to this posed by a broken energy policy.

Bryn Kewley of the Energy Bill Revolution spoke of the absurdity of expecting individuals to invest in the long-term returns of better home insulation when rising UK fuel poverty means fewer and fewer are able to afford to heat their homes at all. He also offered a simple and appealing solution: invest revenue from the carbon tax in social housing stock to provide people living in fuel poverty with better insulation, at a single stroke reducing cold-related deaths, energy bills and energy consumption. Others looked at different aspects of energy policy, seeking alternatives to a UK market in which over two decades of liberalisation and a lack of concern about externalities have been dominant themes. This has resulted in investment in renewable energy R&D having collapsed, the energy production oligopoly being dominated by those companies who profited from the initial privatisation fire-sale, and most if not all major investors plough their resources into the fossil fuel industry, inflating a carbon bubble whose value is reliant upon resources we know we cannot afford to use. Partial solutions to this situation discussed at the conference included divestment from fossil fuels (as represented by a workshop delivered by UCL’s Fossil Free Campaign, part of a growing international movement for university divestment from the fossil fuel industry) and lessons from Germany and Denmark about intelligent market regulation to support community renewable energy. “The only truly progressive thing Coca-Cola could do is to go out of business.” So said Tim Lang, warning the conference how public health dimensions of food policy had transitioned in his lifetime from questions of how to produce sufficient food to prevent malnutrition, to how to control its rampant overproduction. He described a supply-driven food market that produces a situation in which it would take 4 planets for all of us to eat like an American (and 2-3 of them to support the EU); and a system of international trade liberalisation policies that spread this market globally, crippling local systems of more sustainable agriculture and diet in the process.

Buy right, recycle the packaging, and you’ve 'done your bit’. The last objectives on DEFRA’s list come to the crux of the problem: a focus on behaviour change views individuals primarily as consumers, rather than citizens, and the answer to all ills as being to provide more information and then to enable the unrestricted exercise of consumer choice. This approach breeds complacency, a theme touched upon by both Andrew Watkinson and David Pencheon, whether in the 65% of the UK public who feel they are doing their bit for the environment, by recycling and buying energy efficient fridges, or in the doctors “too busy saving patients to save the planet”.

It also neglects the many societal issues already discussed. Furthermore, this individualisation of responsibility carries much the same risks here as it does in health promotion – ineffectiveness, rising inequality, and stigmatisation.

David McCoy, the current chair of Medact, provided a striking illustration of these risks – showing us why an agenda for ‘sustainable development’ based on the neoliberal argument that 'a rising tide lifts all ships' would see the eradication of extreme poverty only in another 100 years. Moreover, tackling poverty through attempts to promote continued economic growth across the board, as opposed to a greater focus on wealth redistribution, requires a 97.5% reduction in the current carbon intensity of production to stand any chance of keeping to the 2C warming threshold. Even then, this would be at the cost of vastly increased inequality (with immense resultant damage to health and wellbeing, and to societal cohesion). It is clear that we need to seek another approach. The 2014 Healthy Planet conference did not present such an approach in its entirety, but presented some steps that could be taken towards it. The rest of the story is up to us. Contact: [email protected] Alistair is a current medical student at the University of Sheffield, unable to sever ties with former life in physics and philosophy, writing his blog, Unprincipled: bioethics against individualism, which is chiefly on health care ethics with a consequentialist/communitarian/feminist-allied flavour; occasional musings on related issues in philosophy of medicine.  Photo ©Tony Ray-Jones/RIBA Library Photographs Collection. Photo ©Tony Ray-Jones/RIBA Library Photographs Collection. This blog was originally posted at http://saherhasnain.wordpress.com/2013/01/15/environmental-justice-case-study-pepys-estate-deptford/ on January 15, 2013 by saherhasnain The scenario: A social housing estate in Deptford of Lewisham, London, situated on the banks of the Thames, near a busy transportation route and an industrial site. It was previously the Royal Victoria Dockyard where British warships were constructed. It is characterized by the presence of a number of housing blocks, the completion of which resulted in winning a Civic Trust design award. The area has also been refurbished in recent times. Primary site for background information on the location: ukhousing Problems: The estate has faced a number of problems over time: 1. Physical and social changes accompanied with the newer development, of which the singleaspect blog gives a richer description here 2. Noise pollution from a scrapyard near the center of the estate. The Royal Docks nearby also suffer from noise pollution, but from airplane traffic from the London City Airport. This site is a shining example of citizen science and successful multi-stakeholder collaboration at play. The citizens were assisted by the “Mapping Change for Sustainable Communities” by the London 21 sustainability network and University College London under the UCL-led UrbanBuzz Programme. London Sustainability Exchange, under the Environmental Justice programme provided the second pilot area. The citizens were taught how to use the noise monitoring devices, took their own measurements and made their own map. Further, detailed information on the mobilisation of the residents and the participation of the Mayor and Environment Agency can be found here and here. 3. Air pollution problems also arising from the same scrapyard and proximity to traffic routes, also analysed as part of the citizen science initiative through the London Sustainability Exchange. This time, the citizens took samples to analyse air quality using diffusion tubes for NO2 levels, Eco Badge ozone detection kits and a novel surface wiping method. The results were analysed through the Lancashire University and the results were translated into a series of maps. This contribution influenced the siting of air pollution monitoring units near the estate and it is hoped that the information will help with addressing the environmental quality concerns of the community. Further details can be found with mappingforchange.org.uk The Pepys Estate area can be viewed on google maps below, with reference to the towers, transportation routes, metal and waste recycling plant, Pepys park and the community forum: Gabriele Messori and Izzy Braithwaite Adapted from a blog post at http://climatesnack.com/2014/01/30/cough-for-coal-at-cop19/#more-1673  Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Our team taking part in Cough4Coal outside the 'Coal and Climate Summit' Neither of us had imagined we’d end up carrying a pair of giant pink lungs in front of the Polish Ministry of Economy on a cold November morning. Why were we there? It’s a long story… We were in Warsaw for COP19, the annual UN climate talks (COP = Conference of the Parties). The aim of the talks is to reach a global deal to tackle climate change in 2015, which will come into force in 2020. We went as part of a delegation of students from Healthy Planet UK, a small, student-led group which seeks to raise awareness about the links between climate and health, and to advocate for UK policy that benefits both health and the environment. As students, researchers and young people, our motivation was the growing body of evidence that climate change poses a major threat to global health, and that sustainable development presents major opportunities for public health. Examples of such climate-health synergies (sometimes called health ‘co-benefits’) can be found across energy, transport, housing and food policy – and quite possibly elsewhere too. Air pollution – bad for health, bad for the climate We know that greenhouse gas emissions affect health indirectly through their contribution to climate change, via changing temperatures and rainfall patterns. Although carbon dioxide has no direct health effect except at high concentrations, it is often, if not invariably, produced alongside other air pollutants. These include substances such as particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen and sulphur oxides, which are emitted both in energy production and motorised transport. Some are greenhouse gases themselves, and all are harmful to our health with myriad effects on our lungs, blood vessels and even cancer risk. The cumulative impact of chronic exposure shortens lives and exacerbates a range of other medical conditions. Around the world, man-made outdoor air pollution accounts for an estimated 2.5 million excess deaths every year. Indoor air pollution (much of it from inefficient cookstoves) accounts for at least as many again, which means that overall air pollution is one of the leading killers globally. Lessons about how politics works… Given the clear evidence that air pollution from burning fossil fuels is so bad for health, combined with the urgency of tackling climate change, you might think governments would be rushing to capitalise on those win-wins. This is where the inflatable lungs come in. Whilst some countries are already taking the kinds of steps that we need, cutting emissions and simultaneously reducing air pollution, over the course of the talks it became fairly clear that some others are working very hard to promote a fossil-fuel dependent future. Almost all of the conference sponsors were fossil-fuel intensive industries. Even more astonishingly, just one day after a summit on climate change and health, organised by the newly-formed Global Climate and Health Alliance, the Polish Ministry of Economy hosted an “International Coal and Climate” summit in parallel with the COP. Feeling that this was outrageous, our team joined many other groups to take part in ‘Cough4Coal’: a public action staged outside the Coal Summit. The stunt involved a series of scenes alternating with speakers from Poland, the Philippines and the UK – one of our team – with the impressive accompaniment of a 7m tall pair of lungs. This was intended to be a visual symbol of the direct health impacts of burning fossil fuels, but also of the less direct health impacts of climate change. Tip of the iceberg

Climate change has been described as “the greatest global health threat of the 21stCentury” by the leading medical journal The Lancet. A 2012 analysis by the DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor arrived at a total of 400,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2010, the greatest burden within this being due to hunger and diarrhoeal disease. However, it is by no means clear that it is accurate to simply extrapolate the future burden due to climate change from the impacts seen so far. These may well be the tip of the iceberg, given that we’ve only seen limited warming relative to what is projected for the coming century. What are the main health impacts of climate change? They range from increased heat exposure, a particular problem among older people and manual labourers, to extreme weather events (which can often affect mental health particularly severely). Changes in the distributions of infectious diseases, and malnutrition and/or starvation due to effects on food production, are equally important. The indirect impacts, such as exacerbation of poverty, migration, and conflict, are both harder to attribute to climate change and significantly harder to forecast. Such impacts are likely to be non-linear and could well be very large indeed – especially with the levels of warming scientists are currently projecting in business-as-usual scenarios. For those interested in finding out more about the health impacts of climate change, we've compiled a summary here. Bridging the gap There may also be pragmatic reasons for framing climate change as a health threat; namely that it connects to people’s own lives and the things they value. In a 2012 study by Teresa Myers and colleagues, a test audience was presented with articles that discussed climate change from a range of different perspectives. Right across audience segments, the articles emphasising the health frame were more likely to elicit strong support for mitigation and adaptation policies than those focusing on the environment or national security. The second working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s fifth assessment report will include a substantial chapter on human health, which could present a useful opportunity for more public communication about climate change using the health frame. It is clear that the stakes are high for health if we continue on our current path. The evidence that action on climate change can benefit public health in all regions is strong – and growing. Emphasising the health implications of climate change can be a powerful way to engage a wider audience in the issue, and everyone with an interest in human health, or just the future of our planet, has a role to play. Not to suggest that you’d need to carry any giant lungs in front of government departments – though by all means get in touch if you’d like to… Alicia Pawluk Negotiations in the United Nations can often be lengthy and complex. For a succinct summary of today's negotiations, please view the overview below. Alicia Pawluk Implementation of adaptation and mitigation measures is reliant on strong financial commitments. Therefore, developed countries are called upon to contribute to adaptation measures for developing nations. Below is a transcript from the COP 19 High-Level Ministerial Dialogue on Climate Finance, which discusses some of these issues.  Image source: UN_Spokesperson on twitter (click for link) Image source: UN_Spokesperson on twitter (click for link) Ricardo Tavares Da Costa This event was probably the highlight of the COP so far. At the start, the Prime Minister of Poland, Donald Tusk, addressed the audience, underlining the delicate and complex environmental issue we are trying to deal with in this conference. He argued that mitigation should not be associated with high costs, and that shale gas might be a sustainable solution. The audience was not impressed. The Secretary-General of the United Nations, Mr. Ban Ki-Moon, started by presenting his condolences to the Philippines, and emphasising the urgency of action: 'the climate science is clear and that we must rise to the challenge. The scale of our action is still limited, but there’s hope and opportunity. We need to reduce our footprint and walk towards carbon neutrality. Our targets must be bolder and we must send the right policy signals for investment. Plan not only for your country but for your neighbour and your neighbour’s neighbour, for your children and your children’s children'. Leadership John Ashe, President of the UN General Assembly, spoke next: "We in this room, the UN family, must reach a deal by 2015 and we cannot ignore the need for real implementation and progress. There is currently a wealth of knowledge and experience to limit emissions. We have good solutions, but we need to deploy them faster. Outside this room the world is becoming increasingly frustrated by the pace of these negotiations. Why are we not fulfilling our roles as leaders? Push back and say yes! We will act today! Right here, right now! Do not do it for yourself, do it for the present generation and for the ones to come". The Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Christina Figueres, spoke next, with characteristic passion: "The Conference of the Parties must respond to the need for climate action and we have a strong case for it (e.g. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). We need to focus on what is feasible and necessary and we need courageous leadership. I know you can, I know we can, so let us do it. Equity The President of Tanzania Mr. Jakaya Kikwete followed: "Africa suffers more than any other continent, despite having the smallest carbon footprint, less than 1t/year and not likely to exceed 2t/year by the end of 2030". This is a key point in terms of health equity: those least responsible are those who's health is most vulnerable to, and most affected by, climate change. This is of course also true in terms of future generations, a point which has been highlighted by extensive work on intergenrational equity by YOUNGO, but this area is still largely absent from draft texts. It is clear that there is a strong and urgent case for action, and that equity needs to be a central part of the agreements made. Now we must push hard to ensure that real and meaningful progress is made in the last week of the talks, and in the next two years leading up to 2015. Alicia Pawluk Whilst negotiators struggle to come to a consensus, time is slowly running out at COP 19. Healthy Planet UK has made many excellent contributions to the climate meetings, and has had the opportunity to listen to many world leaders. In order to get an idea of what a typical day would be like, we've attached our daily summary below. Please follow us on twitter @HealthyPlanetUK to get more regular and detailed updates!  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. It has been quite an experience being out in Warsaw for the climate summit so far, both good and bad - and very tiring! The first week at COP19 was spent mostly finding our feet in Warsaw and at COP19 (the national stadium is a maze!), getting our heads around the negotiations - and just how visible the corporate influence is, with sponsors ranging from coal to car and aviation companies, taking the term greenwashing to an entirely new level (could be a strong case for something similar to Article 5.3 of the WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control here, we think!) We've also had the chance to meet and talk to members of the UK government delegation, from both DECC and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, thanks to our friends over at UKYCC, which was particularly interesting. And we found ourselves in shock - and anger - after the irresponsible moves backwards on climate domestically by both Australia and Japan, especially coming just after the Philippines' lead negotiator Yeb Saño's historic and very moving speech about the devastation wrought by Typhoon Haiyan and his announcement that he was going on hunger strike for the duration of the talks unless there was meaningful progress.  The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action The giant punk lungs of the Cough4Coal action On Monday, we took part in 'People Before Coal', a protest action outside the Ministry of Economy who were - outrageously - hosting a 'Coal and Climate' Summit during the second week of COP19. Perhaps 'coal versus climate' would have been more accurate if you take a look at the World Coal Association's 'Warsaw communique'... Although the fact that the summit was taking place at all is a travesty, the demonstration was a colourful and exciting gathering of people from all over the world; speakers from Poland via the UK to the Philippines and many participants from all over Europe, gathered to highlight the health impacts of coal, on both people and the planet - with these amazing giant inflatable, breathing lungs (!) which were made by #Cough4Coal. There were three scenes in total, showing that the dirty energy future the coal industry's lobbyists are trying to sell us with their Coal Summit is not the clean, healthy future we want. As Christiana Figueres put it at the Summit, "we now know there is an unacceptably high cost (from burning coal) to human and environmental health".  Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Philippines negotiator Yeb Sano, at a solidarity rally for his hunger strike. Along with some of our friends from the International Federation of Medical Students' Associations (IFMSA), we took up the role of young health professionals enthusiastically, with one of our delegation speaking in the gap between two of the scenes about how coal impacts health - both through the air pollution it creates, and through the health impacts of climate change. Some of our photos from the stunt are on the right, with more here; there's also a great blog from 350.org here. One of the best things about COP19 has been the chance to connect up with and talk to other young people from around the world, many of whom have gone to great lengths to fundraise to come and overcome immense obstacles in their fight for climate justice - although our backgrounds and organisations are different, we share a common cause. And it is clear that our governments are currently making nowhere near enough progress towards a binding deal that will keep the planet below dangerous temperatures which would pose a major threat to health. The last few days are likely to focus mainly on Loss and Damage, but - as Yeb Sano has eloquently reminded us - it is essential that we don't lose sight of the ultimate point of the UNFCCC, which is to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate change. At present, the vested interests that rear their heads through 'fossil-friendly' governments like those backing down on climate ambition, are still succeeding in delaying that process for as long as possible. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed