|

You may have noticed a running theme in the posts on the HPblog recently; we’ve been working a lot on divestment – convincing the health sector to stop funding the companies driving climate change, and instead to take its commitment to ‘do no harm’ seriously and move its money towards those working to achieve the energy transition our planet and our health requires. Health sector divestment has taken a huge step forward in the past month, since the Guardian newspaper launched its ‘Keep it in the Ground’ campaign, calling for divestment from the fossil fuel industry. What’s particularly notable about the campaign is their chosen targets – the two biggest private global health funding organisations in the world, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. It’s hard for anyone with more than a passing interest in global health to criticise the Wellcome Trust; Wellcome-funded research has achieved extraordinary advances in healthcare. They are more willing than others to fund research involving higher levels of risk, complexity and uncertainty, an approach typified by their making exploration of the connections between environment, nutrition and health one of their five ‘key challenges’. Moreover, their commitment to transparency – whether in championing open access to scientific research or in making the details of their investments freely available to the public – pervades all the Trust’s actions. But there would be little virtue in such openness if none were willing to challenge them when mistaken. Their stance on continued investment in the fossil fuel industry – as outlined in a recent Guardian article by Director Jeremy Farrar – demands such a challenge. We agree with much of what Farrar has to say. That climate change, as one of the greatest threats to global health of the 21st century, demands concerted action from health organisations. That this requires a commitment to a rapid decarbonisation of the global economy in order to remain within a 2C warming carbon budget. And that consideration of the impacts on human health and wellbeing need to be at the forefront in planning a just and sustainable transition. However, where we disagree is in the role of fossil fuels – and the fossil fuel industry – in making that transition.

He also proposes that it is from within the fossil fuel industry that the necessary decarbonisation will come, and the best way to achieve that is from within, as an active and engaged shareholder. But it is difficult to see how shareholder engagement alone could bring about the scale of transition needed with the required urgency (the IPCC’s 2C carbon budget will be exhausted by 2036 at current rates). Health institutions, more than any other organisations, should be aware that businesses stop responding to shareholder engagement when that engagement challenges the very core of their business model – it’s why it failed with the tobacco industry, and why it’s failing now with fossil fuels. Farrar is optimistic about the role of fossil fuels in a low-carbon economy – citing natural gas and carbon capture and storage as central components – but it is hard to reconcile this position with evidence that half of already-known gas reserves will have to remain unburned to stay under 2C, and that CCS will do nothing to alleviate the health burden of particulate air pollution.

Nonetheless, selective engagement may have its place alongside divestment. But it is only possible with companies who display a realistic commitment to keeping warming under 2C – one that moves beyond words. We applaud the Trust’s acknowledgement of the inconsistency of coal and tar sands development with a healthy climate. But so too is pursuing Arctic drilling, not to mention funding attempts to undermine climate science or legislative efforts on mitigation policy – of which companies in which the Trust invests are guilty. For companies that fall short of the required action, divestment must follow. While we focus here on the Wellcome Trust, that is only because their commitment to public debate permits us to engage in this conversation. The same arguments apply to all health sector organisations, who share the same responsibilities for health of people and planet alike. If, like us, you're convinced that it's time for health organisations to ditch their dirty investments, here are a few things you can do:

0 Comments

In our previous blog, we discussed the historical origins of and ethical judgements behind the 2C warming goal in international climate policy, and what 2C of warming would mean for global health. These theoretical issues aside, the 2C bottom line occupies a powerful position in climate organising, because it issues an unambiguous call to action. Limiting surface temperature increase to 2C above pre-industrial averages, as the majority of national governments worldwide are committed to, demands prompt and drastic action – and now is the Time to Act.

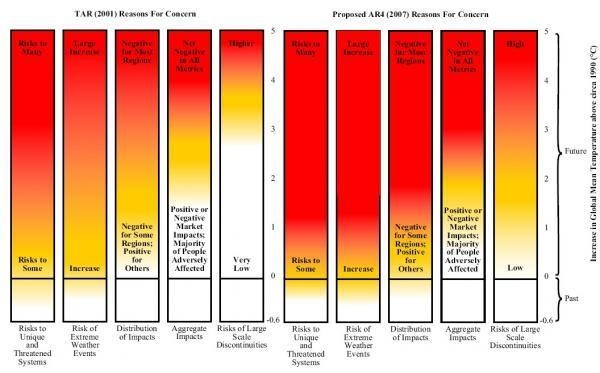

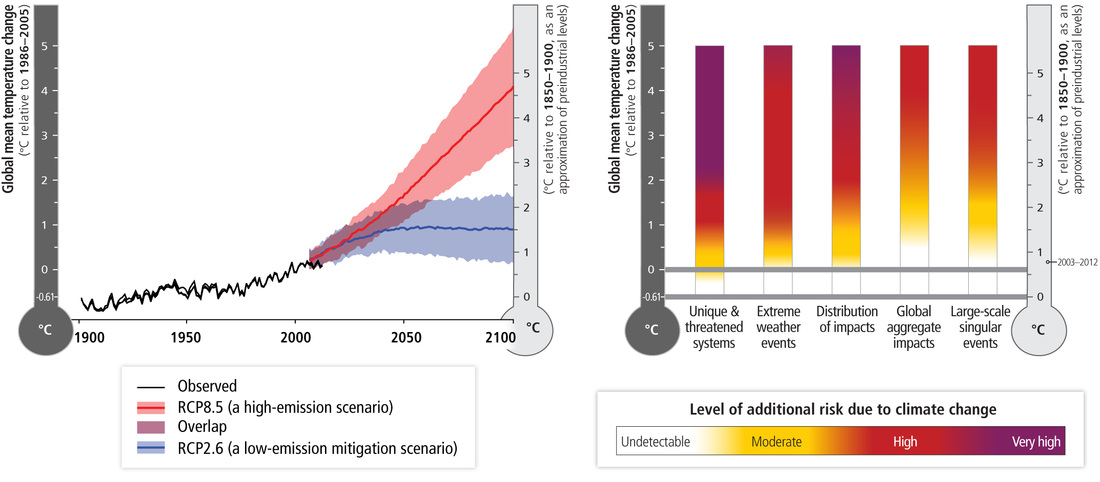

These were some of the concerns that brought a contingent of HP, Medsin, and other sympathetic types to the Time to Act! march last Saturday afternoon. We joined over 20,000 others from across the country, supporting a host of different causes – warm homes, green jobs, environmental justice or just the space to ride a bike – united by the acknowledgement that all of these would play a small part in transforming our society to protect it from the worst excesses of climate change. Medics can be unwilling to get too involved with grassroots campaigning, preferring to retain a professional distance, and with it the veneer of smart-suited respectability. But to participate in a widespread shift of social norms, merely speaking from behind that veneer is not enough. People did not stop smoking or break from the cultural dominance of the tobacco industry merely when doctors warned of the health threats – they did so when health workers themselves stopped smoking, and distanced themselves from the industry through divestment. Given the scale of intersecting fossil-fuel-driven public health emergencies – air pollution and climate change being just the most obvious – it is now unambiguously time for health workers to act. Healthy Planet were in London this weekend for a maximal-efficiency climate and health double-bill: the Medsin 2015 Global Health Conference, and the ‘Time to Act!’ national climate march. We like to take our beard-stroking with a healthy dose of actually doing stuff, and London offered us ample opportunity for both. The theme of the GHC, organised and hosted by UCL Medsin, was ‘The Bottom Line’ – one particularly relevant for HP’s recent work on fossil fuel divestment, given detractors’ concerns about the impact of taking action on their bottom line. Moreover, climate change itself poses the ultimate bottom line – the boundary of a planet no longer capable of supporting a healthy society. Nationally and internationally, this boundary has been quantified in terms of the 2C surface warming goal – the bottom line to which all climate mitigation policy is supposed to add up. But the cultural currency of this simple proposition – that global mean surface temperature increase should be constrained to within 2C warming relative to pre-industrial times – belies the complexity of the underlying science, and the health threats posed by climate change. Three questions immediately suggest themselves. Firstly, why – of all temperatures – pick 2C? Secondly, what do we neglect by making this goal the focus on climate mitigation efforts? And lastly, what do we need to do to achieve it? For all of its dominance in contemporary climate policy, the history of 2C as the limit of ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference’ hardly offers conclusive reasons for its adoption. It came about rather from the efforts of a group of German climate scientists to find a hook that would make the esoteric scientific debates accessible to a policy audience, and motivate substantive action. To do this, they sought a single parameter, and a ‘safe’ limit to that parameter for global society. Surface temperature provided a natural parameterisation, given its close association to the natural and human impacts of climate change. As for the boundary, a helpful demonstration of the motivations is offered in the IPCC’s ‘ember diagrams’ of reasons for concern shown below – the Third Assessment Report (TAR) version shows that, at that time, 2C warming was thought to keep the risks of overall global aggregate impacts (chiefly measured by economic and human costs) low. It was also thought that, at such levels, the risks would remain low of bypassing ‘tipping points’ – step-changes in the natural environment that – like the West Antarctic or Greenland ice sheet collapse – would suddenly and irreversibly alter the climate, or – like seafloor or Arctic permafrost methane release – result in positive feedbacks that would ‘lock in’ further warming independently of human carbon emissions.

But if the 2C goal focuses on global aggregate impacts and tipping points, what does it neglect? Some clues to this are also displayed in the successive ember diagrams. An omnipresent and purely formal difficulty arising from using marginal benefits to determine goals is that such goals will neglect the distribution of those benefits. And, as the embers show, even if at 2C the human cost of climate change to some may be offset by economic benefits to others, the differences between who benefits and who pays are striking. It is well established that those least responsible for climate change are, in general, those who suffer most, and climate change acts as an intensifier for many existing inequalities. This is most strikingly demonstrated in the risks of warming to ‘unique and threatened systems’ – communities and ecosystems that may be lost altogether thanks to climate change. While the ‘global aggregate impacts’ of 2C warming may be manageable, a world that much warmer is one in which many unique ecosystems – coral reefs, or amphibian habitats – may be lost altogether, while some societies – Inuit communities and pacific islanders – will see their way of life melt away, or disappear beneath the waves. One might, therefore, be led to question whether 2C is an appropriate target, given how the science of climate change has developed since its proposal and the normative framework used to arrive at it in the first place. But further, one could question whether surface warming – or surface warming alone – is the appropriate parameter to be targeting at all. A high-profile editorial in Nature last October raised precisely this question, suggesting that instead a host of planetary ‘vital signs’ should be considered to map the differential impacts in different regions and on different systems of a changing climate. While some questioned the scientific validity of their suggested alternatives, and others endorsed the pragmatic value of the 2C target, the critique gained traction perhaps because it highlighted the shortcomings of one of the few relatively uncontroversial propositions in climate policy. But, even if one were to find a perfect way of measuring climate change, would setting our targets in terms of climate change alone be adequate? For, as Christina Figueres (secretary of the UNFCCC) has said, climate change is not a disease; rather, it is a symptom, and only by looking at other associated symptoms can one come to an accurate diagnosis. A host of other planetary boundaries – biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, land use change to name a few – are affected by the same social, economic and political processes driving climate change. Many of these are in fact taken into account in international climate negotiations – but to look at surface temperature warming alone neglects some major associated threats to human and planetary health. For all its shortcomings, however, 2C has one major advantage; it’s catchy. It expresses a simple, accessible objective, one that both demands immediate action while still being achievable. And as an explicit commitment of most governments worldwide, its implications for the need for rapid decarbonisation if we are to stay within a 2C carbon budget gives it potent campaigning value. Few propositions could win equal support from climate activists and the governor of the Bank of England. It’s this cultural currency that has made the fossil fuel divestment campaign the fasting-growing of its kind in history. For more on the advocacy and activism that has grown around this bottom line, see our next blog…

To mark Global Divestment Day, we're asking as many people as possible to share their divestment stories - who they want to divest (or have already got to divest), and why. Maybe you're a nurse who wants your College to move its money; maybe a doctor and you've already switched your own bank to one standing for a fossil-free future. Maybe you're involved in one of the hundreds of university, faith group, local authority or other divestment campaigns already taking place worldwide. What have your successes been? What challenges do you face? And what does it mean for health? One way of making your case clear is demonstrated by the great start to Go Green Week made by the medsin national committee an branches from Leeds, Liverpool, Newcastle, and Sheffield. We joined forces to make the health case for divestment, which you can see in this video. If you enjoyed it, please share widely!

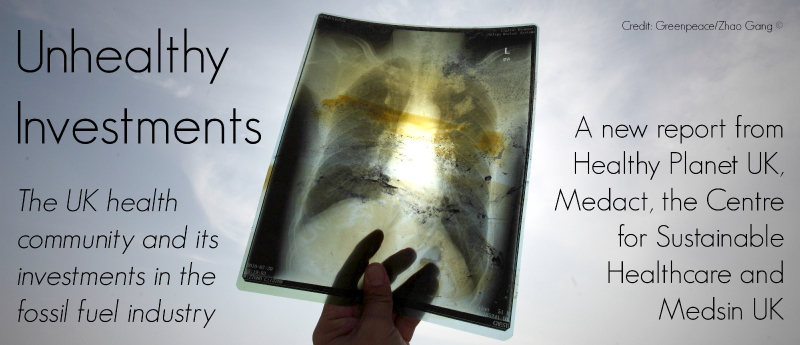

Whatever you do, have a great Global Divestment Day! Last Tuesday evening, we launched our Unhealthy Investments report on fossil fuels, human health, and divestment (as you'll no doubt by now be sick of hearing). It didn't take long to see an impact - by Wednesday, it was already being cited in Parliament! A new Early Day Motion, tabled by Green MP Caroline Lucas, calls on the Trustees of the MPs' pension scheme to divest from the fossil fuel industry, citing the potential devastation to human and planetary health that would be caused by continued unrestrained dependence on fossil fuels.

Don't know what to say? Start with our template letter - though remember, MPs are always more likely to respond if you make it a bit more personal.

For more ideas on how to take part in Go Green Week and Global Divestment Day, take a look at our inspiration pack for medsin branches - or, as ever, get in touch! Yesterday evening marked the launch of Unhealthy Investments, the report on climate change, global health and the fossil fuel industry. Medact and Healthy Planet produced this report, published alongside the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, the Climate and Health Council, and medsin, as a tool to help health workers make the case for their representative bodies, funders, and other health sector institutions to divest from the fossil fuel industry. The report argues that:

There has been significant coverage of the report’s launch in various venues.

What now? This is only the beginning; the report and related resources, and the coverage and debate surrounding it, provide the perfect tools for healthcare students and health workers to take the case for divestment – and action on the health impacts of climate change – to their universities, trusts, unions, professional organisations, representative bodies, and other representatives of the health community. How can we go about doing this? Some ideas:

For more on divestment and health, visit the Unhealthy Investments report site: www.unhealthyinvestments.uk.

I have been involved with the fossil fuel divestment movement over the past year, both with the University and through Healthy Planet UK, after coming to terms with the enormity of climate change and the need for urgent action. As a medical student I am compelled by a similar duty of care towards our ecosystem, on which our health depends, and am called to respond to its current symptoms of distress. Divestment offers a way to treat one of the root causes of these symptoms – the continued burning of fossil fuels – through moving investments away from the fossil fuel industry whose business model relies upon burning reserves which hold over five times that which is safe to burn if we are to stay below the 2 degrees Celsius limit of global warming[1] Akin to the health sector leading divestment from the tobacco industry, there is a similar narrative in the response to the health threat of climate change further weighted by tactics utilised by the fossil fuel industry to thwart climate mitigation policy and mar public perception of the reality of climate science[2]. UK universities hold around £5.2 billion worth of investments through their endowment funds in the fossil fuel industry[3]. However, divestment is not simply a matter of money, most divestment decisions have been driven by a moral case. It rests on a simple principle -if it is wrong to wreck the planet, then it is wrong to profit from that wreckage. For the medical tradition, investing in fossil fuels can be seen to contradict the fundamental principle to “first do no harm”. So far 21 universities, 35 cities, 65 religious organisations and numerous other organisations from around the world including the British Medical Association have committed to divesting from fossil fuels[4].

Medical institutions and the health community have a unique awareness of climate change through its current and future impacts on human health, but also through the potential immense health co-benefits of tackling climate change such as reducing the disease burden of air pollution, which has recently been attributed to 2000 premature deaths annually in Scotland[5], and encouraging active travel through reducing our reliance on fossil fuel guzzling cars. This gives an important dimension to the divestment dialogue and the engagement of medical schools and health organisations is sure to be very valuable. On the 3rd February, Healthy Planet are publishing their report “Unhealthy Investments”, co-authored with MedAct, The Climate and Health Council, Medsin and the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare. This will be a crucial step towards further engagement on fossil fuel divestment from the health sector. It will involve a panel of expert speakers to discuss the question of whether organisations which work to improve health should continue to invest in fossil fuel extraction and production companies. Should the health sector be taking more of a lead in this issue? There is certainly great potential in engaging with the process and evaluating how best our pension and endowment funds can be invested towards a healthier and more sustainable future. Eleanor Dow – new Deputy coordinator of Healthy Planet UK, medical student at the University of Edinburgh References [1] http://www.carbontracker.org/ [2] http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/en/campaigns/global-warming-and-energy/polluterwatch/Dealing-in-Doubt—the-Climate-Denial-Machine-vs-Climate-Science/ [3] http://peopleandplanet.org/fossil-free [4] http://gofossilfree.org/commitments/ [5] http://www.foe-scotland.org.uk/air-pollution In recent years, the UK medical establishment has come to take increasingly serious the warning of the Lancet-UCL commission that anthropogenic climate change may pose the “greatest threat to global health of the 21st century.” This has manifested not merely in rhetoric, but also in substantive action – most recently, in the British Medical Association’s vote to form an alliance for action on climate and health, and to divest from the fossil fuel industry. But it has long been recognised by environmental health workers and campaigners that environmental health threats do not respect national borders, and action to remediate them must consequently be similarly international in nature. It’s for this reason that the attention of many across the world will be directed towards the proceedings of the General Council meeting of the Canadian Medical Association, currently taking place in Ottawa, hoping that Canada’s doctors will engage with the threat to human and planetary health posed by our continuing dependence of fossil-fuel energy sources.

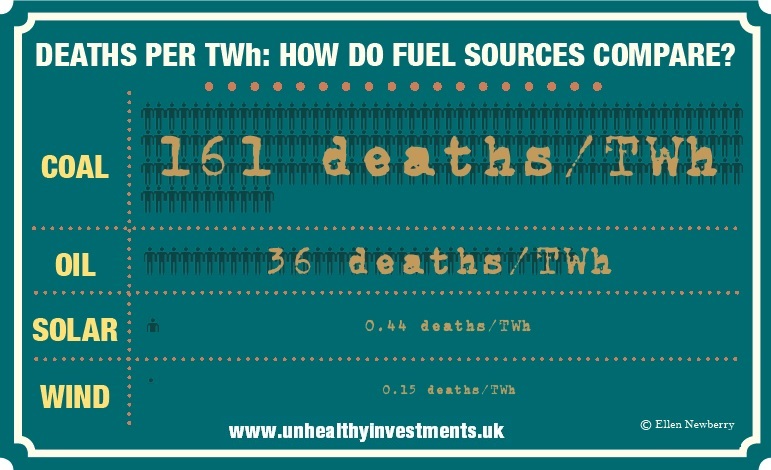

The General Council will vote on a series of motions brought forward by the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, calling on the CMA to take a stronger leadership role in acting on the health effects of climate change. In particularly, they want the CMA to acknowledge the role played by fossil fuel dependence in driving climate change (as well as producing the air pollution responsible for 1 in 8 deaths worldwide in 2012), and to work towards the renewable energy transition by supporting a coal phase-out and offering a fossil-free investment fund to its members. With the vast death toll of air pollution, the fossil fuel industry’s role in driving climate change and attempting to subvert both climate science and international climate change mitigation policy, and its continued commitment to exploiting newer and more-polluting fossil fuel resources in place of renewable energy investment, there is a substantive moral and medical case for Canada’s doctors to sever their ties with the industry. The main opposition to this case, however, comes less on medical grounds than economic ones – this has been the case in the UK, and is likely to be the case in Canada. However, these economic arguments do not stand up to scrutiny – the fact is that, not only will concerted climate action be better for our health, it’s better for our pockets too. One prominent concern is that the economic costs of breaking from fossil fuel dependence may hurt our health more than the gains from doing so. This is a favourite line pursued by fossil fuel industry-funded climate contrarian Bjorn Lomborg; however, it compares apples with oranges – the world now is not as it was before the Industrial Revolution, and renewable energy technology now provides a viable alternative. Recent estimates of the costs of all-renewable energy infrastructure predict that the additional investment required will be more than offset by longer-term savings (and that’s without even factoring in the economic impacts of climate change). And far from renewable energy holding them back, many emerging economies are finding it central to improving their energy infrastructure – in particular, the easy provision of off-grid renewable energy is making electricity supply to relatively inaccessible regions easier and cheaper – saving lives in the process. When it comes to exacerbating inequalities, then, the ways in which the health, social and economic impacts of climate change will hit the poorest hardest should be of far more concern. It is, of course, vital that the energy transition is brought about equitably – but that is not an argument against its necessity. Furthermore such arguments neglect the ‘social cost of carbon’ – the fact that fossil fuels don’t just make us sick, this sickness costs. The health-related externalities of coal power alone are vast – recent estimates suggest that coal costs Albertans some $300m, while corresponding figures for the EU come to some €43bn, and across the USA it is thought to be a staggering $350bn. These costs add to the potentially huge health cobenefits of a renewable energy transition –a 30-40% reduction in all-cause mortality through increased cycling, two million premature deaths averted with more-efficient cookstoves, or any of the other range of health improvements arising from less air pollution, better transport, healthier diets and more green space. These benefits themselves have positive economic ramifications – for example, it has estimated that the UK’s health service could save £4 for every £1 invested in cycling infrastructure, or £17 billion within 20 years. A second set of economic concerns comprises those rather closer to home, focusing on the impact of severing ties with the fossil fuel industry on the members of the CMA. If CMA members choose to make their investments fossil-free, will this hurt them financially? While such matters are beyond me – and most – to predict, available evidence shows fossil-free portfolios closely tracking, if not outperforming, conventional benchmarks. Continued investment in fossil fuels, meanwhile, risks ex exposure to the ‘carbon bubble’ – the trillions of dollars the fossil fuel industry stands to lose if climate change mitigation legislation (which would make up to 80% of currently-listed fuel reserves worthless) is enacted. While the actions of the CMA are for its members to decide, their decisions will influence not just them – indeed, not just Canadians – but affect the entire globe. Many health workers internationally will be following the events of the next few days with interest, and offering solidarity to CAPE and all CMA members willing to commit to the change we need. Leaving fossil fuels behind is not unaffordable – it is the alternative that is unaffordable. FURTHER READING · Summary of the health impacts of climate change detailed in the latest report of Working Group 2 of the IPCC from the Global Climate and Health Alliance. · The summary argument for health sector divestment presented to the BMA before its Annual Representatives’ Meeting voted for fossil fuel divestment. · The parallels between the fossil fuel and tobacco industries and their impacts on health. Alicia Pawluk

It isn’t a secret that improving your health can have positive impacts on other areas of your life. However, one of the most significant influences health-conscious people can have is on the environment around them. It is clear that there are many ways in which we can help the environment and ourselves at the same time, these are the so-called ‘co-benefits’ of healthy living. [i][ii] When I was in medical school, I began to realize that the symbiotic relationship between wellness and the environment is key to developing a healthy, eco-friendly society. Here, I investigate a few ways that you can help the environment and improve your health at the same time. 1. Use alternative or public transportation. Alternative methods of transportation, such as walking or cycling, reduce fossil-fuel emissions and can improve your cardiovascular health.[iii] By choosing human-powered transport, you are reducing the amount of pollutants in the air we breathe, as well as decreasing your risk of heart attacks, strokes and type 2 diabetes. [iv] Also, by using public transportation, you are encouraging your government to commit to large-scale public transportation projects and are helping to reduce the number of cars on the road. Additionally, by using public transport you are decreasing the amount of fuel-based irritants in the air, and may decrease your risk of developing respiratory illnesses such as asthma. [v] 2. Eat organically By consciously choosing the food you consume, you prioritize both your health and the environment. Organic farms cause less environmental impact by decreasing the run-off of pesticides and herbicides in our water supply. More obviously, eating organically decreases the amount of chemicals, antibiotics, and hormones you consume on a daily basis. This allows your body to detoxify more efficiently, making you less likely to suffer the ill effects of unknown chemicals in non-organic food products.[vi] 3. Buy locally-grown food Local farms are always an excellent choice for both the environment and your health. Growing foods locally means less fossil-fuel used in their transportation and processing.[vii] By choosing local food, you are also supporting farmers in your community and promoting local economic growth. Most importantly, the short distance from farm to fork means that the food can be picked at its peak ripeness and eaten fresh. Thus, local foods are packed with nutrients and vitamins that you may not get otherwise. [viii] 4. Go meat-free Reducing consumption of meat, and in turn increasing the amount of vegetables in your diet, is incredibly beneficial for your health. Vegetarians reduce their risk of chronic heart disease and type 2 diabetes[ix], and increase their intake of fiber, potassium and calcium[x]. Additionally, a recent study has shown that vegetarians reduce their green house gas emissions by an average of 29%.[xi] If going vegetarian is too challenging, reducing meat consumption by eliminating meat one day a week (‘Meat-free Mondays’), can also offer health benefits ix, and reduce green house gas emissions by 22%. xi 5. Spend time outdoors Making an effort to help your environment is much more rewarding when you can reap the benefits. From spending time out in your garden, to hiking through the forest, nature has the ability to restore and revitalize. Whether you prefer to meditate in a meadow or paddle a canoe, being outdoors can reduce stress levels. [xii] *Bonus: if you live in a sunny climate, being outdoors for a mere 15 minutes can give you an adequate dose of vitamin D and promote bone health. [xiii] Author Bio: Alicia Pawluk received her BSc Honours in Medicine from the University of St Andrews in Scotland. Having volunteered at the World Health Organization’s ‘Climate and Health Summit' in Warsaw, 2013, Alicia’s scientific interest in climate change has taken her to a Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Her work on the health benefits of tackling climate change has been published in numerous journals, but her ultimate goal is to develop public awareness of environmental issues. Alicia is currently studying for her Bachelor of Surgery at the University of Manchester in England. References [i] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S074937970800682X [ii] http://www.who.int/hia/green_economy/transport_sector_health_co-benefits_climate_change_mitigation/en/ [iii] http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/resources/data/benefits_research.cfm [iv] http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=195347 [v] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901109001919 [vi] http://www.agronomy-journal.org/articles/agro/full_html/2010/01/a8202/a8202.html [vii] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919210001132 [viii] http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nsinf/fnb/2014/00000035/00000002/art00005 [ix] http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8746358&fileId=S1368980012000936 [x] http://www.fasebj.org/cgi/content/meeting_abstract/26/1_MeetingAbstracts/634.1 [xi] http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/early/2014/06/04/ajcn.113.071589.short [xii] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169204612002642 [xiii] http://ageing.oxfordjournals.org/content/15/1/35.short  Howdy all! My name is Carina. Here is what my face looks like: I come to you fresh from the rocky outback of King's College London, where I have been known to study Medicine on occasion, when the mood takes me. From inauspicious beginnings as a casual recycler, I came to Healthy Planet in a rather roundabout fashion. After the horror of the Rana Plaza building collapse in 2013, I resolved that I wanted to use the modest conduit of my own existence to make decisions that would do less harm to others. And so as my life became fairly traded, "organic" and "sustainable" also bled in. Fear not, I don't sit at home self-flagellating with bean sprouts and hemp; my eco-friendly lifestyle is good fun, surprisingly normal, and only very occasionally smug. Yet while I felt happy with my slimmed-down carbon footprint, I knew that this token gesture of greenness was grossly undermined by the actions of institutions I used or even those I belonged to. At this point, I was prepared to pack up my medical studies and my wicker shoes to board the fight for the environment. Fortunately, before I jacked everything in to save the whales, I found Healthy Planet UK. I drew the dots between air pollution and asthma, between birth rates and biodiversity, between carbon and carcinoma. So begins my reign of admin! My first newsletter went out recently with an update on our Fossil Free Health divestment campaign, climate news and events, and a little touch of whimsy. There's plenty to be excited about! |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed