Izzy Braithwaite From a BMJ Blogs series for the upcoming CleanMed Europe Conference - edited version at: http://bit.ly/13EBL8D The concept of sustainable healthcare and – related to that - how environmental change affects health are not generally taught in medical schools, but I was lucky enough to take part in a student-led national programme on the topic in my first year. I had long been interested in global health and the environment, so was keen to find out more and get involved in this area. The focus of my work has been with the Sustainable Healthcare Education (SHE) Network, for example contributing to a set of downloadable teaching resources and subsequently helping to collate a set of case studies on existing student-selected components. I’ve also been involved in the most recent project on curriculum learning outcomes, organised in response to a request from the GMC, which has been a multi-stage consultation process. The three overarching learning outcomes proposed on the basis of the consultation are to be published online soon and cover: the relationship between the environment and health; the environmental sustainability of health systems; and the ethical and policy-related issues that arise from understanding these two topics, such as how the duty of a doctor to protect health applies to future generations. As I‘ve read more about our impacts on the environment, climate science and the extent to which human health depends on ecosystems and climate stability, I’ve been surprised and concerned by how little of this information seems to reach the general public, including medical students. To help change that, I’ve been running workshops and campaigns with a student group called Healthy Planet UK, in partnership with a larger network called Medsin. Medical educators, students and clinicians wishing to set up more teaching in their medical school often encounter objections that there's not enough space in the curriculum or that these topics aren't relevant. Yet the evidence shows that climate change is an increasingly important threat to global public health, and I think the scope for health professionals to help shift political narratives around environmental issues is often underestimated. If my cohort of future doctors needs to know about tobacco or antibiotic resistance, then surely we also need to understand how changes to weather patterns and ecosystems are affecting, and predicted to affect, health. Equally importantly, we need to be aware of the growing evidence base around the opportunities, termed 'co-benefits', to deal with burgeoning public health problems such as obesity and poor mental health in a way that's synergistic with the goals of sustainable development. Given some of the details I had to learn in pre-clinical medicine, the argument that there's not enough space in the curriculum suggests it’s an issue of priorities. Do we really think enabling tomorrow's doctors to tackle what may well be a bigger health threat than tobacco - especially considering the complete inadequacy of the political response so far - matters less than learning, for example, all the steps of the Krebs cycle? My learning in this area has influenced the way I think about the rest of my education, and I think I'll be a better doctor for it; better able to understand the macro-scale influences on patients' lives, and to contribute to discussions about how health services could be better for both patients and the environment. To create lasting change - whether in sustainable healthcare, climate policy or other public health issues – tomorrow’s doctors require an understanding of the issues, to have had the freedom to discuss them and try out their ideas, and the skills for effective collaboration, including inter-sectorally. Through the SHE network, we are seeking to create this space for students to learn, reflect and debate about the issues, and to develop the skills to help lead the transition to sustainable healthcare. The fourth CleanMed Europe conference takes place at the Oxford Examination Schools from 17th-19th September, and Izzy will be talking about the SHE Network and Healthy Planet's activities during the conference.

0 Comments

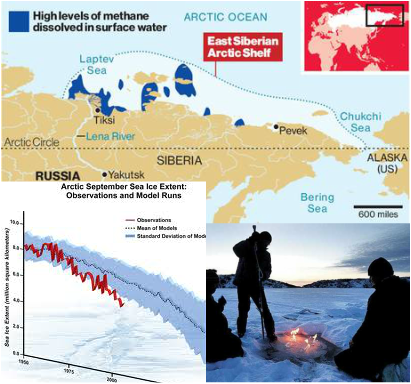

Source: GRAVIS India, http://bit.ly/1bui5ff Source: GRAVIS India, http://bit.ly/1bui5ff by Grace Remmington, GRAVIS intern and one of the Healthy Planet COP19 Support team members. This blog was originally posted at http://gravisindia.wordpress.com/2013/07/09/making-the-link-climate-change-water-security-and-health/, where you can also find out more about GRAVIS India's work Since arriving in India, one of the things which I have been considering is the links between climate change, the water cycle and health. India suffers both extremes of the water cycle: some areas experiencing many drought years, others experience heavy flooding. The apocalyptic photographs of the flooding in Uttarakhand, with a death toll of at least 1000 people, stands in direct contrast with the area of India, the Thar Desert, that I have experienced. Last Tuesday (2nd July), the UN’s World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) released its climate report on the last decade which exposed the climate extremes that have occurred between 2001 and 2010. The report recorded an ‘unprecedented’ rise in climate pattern which is estimates has resulted in more that has 370,000 deaths due to heat waves, flooding, tropical cyclones and other phenomena. The most notable of these was the 2010 flooding in Pakistan which affected over 2 million people. However, what I have begun to notice, living and working in a very arid region, is that the WMO figure is really only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to climate-related, specifically water-cycle related, deaths. The real human cost is much higher. The effects of events such as flooding are immediate and provide a very visual and panoramic spectacle of a climate-related disaster. In these cases, the links between extreme weather events, and their resulting problems, are easy to make; the immediate evidence is hard to deny. For example, the link between climate change and increases in cases of malnutrition is evident. A low yield of crops after a failed rainfall is causally linked and the evidence is relatively hard to refute. A change in the rainfall, such as a failed monsoon, creates low soil moisture which affects crop yield, in turn causing farmers to have less access to both the food they grow and the food they can afford. This trend is easy to evidence for several reasons: firstly, it happens in a short, controlled timeframe and, secondly, the links between drought and fluctuation in climate are correlative. Therefore, the causal link from poor yield to reduced food security is a logical one. The problem in recording climate-related deaths becomes more difficult in trying to hold to account the deaths in which the causal link is blurred by other variables and, very importantly, takes place over an extended period of time. There are many examples of these seemingly non-climate related events. The one I will use is one which has become increasingly apparent to me through my work with Gravis: the occurrence of Occupational Lung Disease (OLD). The causal link between climate change and Occupational Lung Disease could be seen as the following: the event of poor rainfall results in a poor crop yield, which impacts on the ability to feed a household and livestock. Due to this shortfall in food and income, farmers must seek alternate employment. Often this need requires migration. One of the most common alternative forms of employment in the Thar is mine work. Workers migrate from rural farms to work in sandstone and marble mining, for example the mines near Jodhpur, where they work long days in the blistering heat with no shelter, little water and no toilet facilities. Further to the lack of provisions for basic rights in a workplace, the employers, through ignorance or negligence, do not provide adequate health and safety in the mines to prevent inhalation of the dust through practices such as wet drilling (as opposed to the prevalent and cheaper dry drilling which creates a lot of dust). This dust contains crystals of silica which lodge themselves in the lungs and accumulate over time. The initial symptoms are irritation and inflammation of lung tissue which then progresses to fibrosis (scarring) of the lung tissue. The effects of silicosis are the collapse of alveoli (air sacs) in the lung, emphysema and a weakened resistance to secondary lung diseases such as tuberculosis. Silicosis limits life-expectancy by an average 15 years and cause early death through respiratory failure and heart disease. The problem with linking silicosis and climate change is that it is not as easily correlated as - for example - a rise in communicable diseases (such as diarrheal diseases) during flooding. The causal link between the two is more complex and runs through many events such as crop failure and migratory patterns. Furthermore, the variability of employer responsibility regarding healthy and safe practices complicates any direct causal link. If the employer took the legal responsibility for mineworkers’ health, it would go a long way to mitigate the effects of Silicosis. However, currently this protection is not happening; therefore, after years of failed rainfall, farmers become forced environmental refugees who are economically disempowered. They are living a life of subsistence exacerbated by environmental problems. Therefore, they do not have the economic independence to demand better working conditions or the opportunity of alternative employment. They are working for the continued survival of themselves and their families. The other issue which causes a difficulty in creating a link between climate change and many deaths, such as those arising from Occupational Lung Diseases, is that they occur over a much longer time period. Therefore, unlike many casualties of climate change, the impacts are not as easily and directly demonstrable. The effects of climate change take place within a slow time-frame, unlike the rapid human impacts of environmental changes seen in disasters such as flooding. Climate change is the most fundamental issue facing this planet, economy and people – particularly the world’s poor – and it is time that global society recognises the full extent of its effects. These are not just the direct and immediate costs – those easily viewable and provable – but also about making the link between the complex and gradual impacts which are just as catastrophic. In this sense, the loss of 370,000 lives reported by the WMO is just the tip of the iceberg: we need to reach deeper into the complexities of the human cost of climate change in order to protect the poorest people on the planet. Grace Remmington is currently volunteering with GRAVIS working on documentation and research. Following her graduation from the University of Southampton, she has spent this year working overseas in India and in working rural development in Nicaragua. She is planning to study Water Science and Policy in 2014, and will be part of the HP Support and Comms team during COP19. Follow her here: @graceremmington 18/6/2013 Methane 'plumes' in the Arctic, positive feedbacks - and why we all need to act on climate changeRead Now Jake Campton, UWE ""Dense plumes of methane over a thousand meters wide" have been discovered leaking from the permafrost around northern Russia following continued warming in the region - and the rate of release has been accelerating. Why does this matter? Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with 20 times the warming potential (heat-retaining ability in the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide. That makes it extremely problematic. The total amount of methane beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves, meaning a planetary time bomb is currently ticking in northern latitudes. It is not only the scale of these outflows that is unprecedented; it is also the alarming frequency at which they are occurring. Dr. Semiletov’s research team that made the discovery found hundreds of these plumes, similar in scale, over “a relatively small area”. Our planet’s weather has been thrown into disarray in recent years; the last decade has witnessed more weather records broken than the entire last century! The more we continue to heat the Earth, the quicker the permafrost will melt, increasing the rate methane can escape its icy prison; a positive feedback effect (Arctic ice is not the only one either, there are a lot in action - see this page for info on a few others). We will eventually become locked in by this effect, with heating leading to more rapid heating, accelerating the whole process further still. Add in the reduced albedo effect from the rapidly receding glaciers of Greenland and surrounding area and the danger we are in becomes clear. We are in trouble. It doesn't take too much time reading up on climate science - as described in a World Bank report just out - to work that out. What's more, it's not just an issue for the polar bears; it's a health issue too. Humans are reliant on the environment and most critically, a stable climate to provide food; it doesn't magically appear on our supermarket shelves (even if that's what many kids now seem to think!) The last few years have seen intense droughts ravage vast swathes of the planet, including the major grain producing nations: Russia, Australia and the U.S. among others. By mid-2012, the U.S only held enough grain for just 21 days. The increased scarcity of its staple crops caused sharp price spikes too - corn reached $8.39 a bushel by August 2012, an all-time record. Farmers were forced to cull large numbers of livestock as they suddenly became too expensive to feed. Are these the sorts of trends we should expect to continue looking forward? Grains becoming so expensive that meat is affordable only for the richest? And what about the poorest nations? What will the implications for malnutrition and food security be if the main exporting nations are unable to meet export demands? In 8 out of 13 recent annual harvests, global consumption has exceeded production, eating away at our grain buffers. A few more volatile growing seasons, and we could all be in real trouble. No nation is safe from a perturbed Gaia… I blame a lot of people for this current mess. Not enough people care. That fatalistic idea, 'I'm one person, nothing I does matters' is, frankly, crap. 65 million UK inhabitants doing their bit, and I don't mean just recycling here, would make a substantial difference. If we were also to factor in 700 million Europeans and 300 million+ Americans - not to mention a billion plus Chinese and others - you can see the potential for drastic, meaningful, global change. You see, you are not just one person; you are every environmentalist that plays their part in this conundrum. You are hundreds of millions of people. That is where our power to change lies; in sheer numbers. Industry is changing, albeit reluctantly, now society must change, too. My biggest fear is that most people won't act. It's a failure of our education system, a neglect of our moral responsibility - and it could be a catastrophe for humanity. I realise we have had many decades of industrial pollution before us, but they weren't aware of the implications of their actions - and they were also far fewer in number, each consuming much less. If current trends continue, things could become truly and irreversibly messed up within a couple of decades and that terrifies me. It will be this generation and our immediate predecessors, the ones that peered into the precipice, who will be blamed. We could still make a meaningful impact on the current situation but I worry that we won't. We could have a great future ahead of us, but many forget that humanity and the environment are inherently intertwined. Until we recognise Earth as the delicate, dynamic and precious entity that she is, and treat her with the respect she requires, we will continue unabated along this perilous path. The bridge is out up ahead, we need to change paths. I sometimes worry that the window for action has already closed, it’s something I feel bitter about, something that angers me greatly. There are people out there who are particularly responsible, who keep ignoring the problem, and their negligence is literally costing the Earth. I believe that if more people shared my sense of impending danger more would get done. I’m not sorry if this offends you, it's probably because you are the sort of person I am referring to. If my words are intrusive in to your way of life, maybe your way of life is part of the problem. When something so big is at stake, I think you have to ruffle a few feathers - feel free to comment if you wish to discuss anything further, I’ll gladly respond. I know its complex, and it can feel like whatever you do is a drop in the ocean -sometimes it's difficult not to feel frustrated and concerned - but there is lots you can do. Start off by educating yourself; there's a lot of information out there - but always be critical. Outspoken anti-climate behemoths like the Koch brothers, use political and monetary leverage to fund anti-climate change ‘research’ and spokespeople to help maintain the status quo for their incredibly irresponsible and selfish gains. Be wary…  Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Are you a carbon addict? Take the test... Below are some ways I try to reduce my impact on the environment. They're small steps that don't require much effort - why not give some of them a go? Eating less meat - I can't understand why people assume it's a right and a necessity to eat meat every day, but this is one of the most effective ways you can reduce your burden, as well as making yourself healthier in the long run. We have molars for a reason; we are omnivores, not carnivores. Cycling and walking wherever you can is another great step - driving a few miles down the road is a missed opportunity to stay fit, a pointless waste of petrol and needless emission of carbon. I realise some people can't - fair enough, but most could. I bike everywhere, I feel great because of it and I’m very fit as a by-product. You could shower instead of filling a bath, turn off plug sockets at the wall to avoid appliances ‘ghosting’ electricity, wash your hands with cold water instead of hot to save energy, boil the exact water you need when making tea, by cloth bags for shopping trips and avoid plastic, use LED light bulbs; expensive but they can last over 30 years and use just 10% of the electricity of halogen/filament bulbs! Wear an extra jumper instead of cranking up the heating in colder times, turn down the brightness on your laptop to reduce energy consumption and there are many more. These may sound like small things, but, when added up and multiplied by the efforts of millions of others, cumulatively, we can drastically reduce our strain on Earth and preserve the environment for future generations, as is our responsibility. Things you do in your daily life matter, and - imperceptibly - help start to shift the norm. However, we need political change too, and contacting your MP and MEP, signing petitions or even getting involved or setting up local campaigns isn't actually as hard as it can seem - Google is your friend here. Anyway, rant over - you're all free to act as you see fit of course, but what I'd really like to say, and excuse my French, is that you personally don't screw it up for future generations because you can't be bothered to act responsibly. Acting together, we have a chance to change our future for the better. There’s no I in team, but there is in humanity. Share yours.  Bangkok floods (Source: UN/Mark Garten) Bangkok floods (Source: UN/Mark Garten) Shuo Zhang Originally published at http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/climate-change-threatens-health-in-the-new-megacities/ Weather was big news in 2012. Australia’s decade-long drought the ‘Big Dry’ ended in May, and the US drought last summer caused a major crop failure. Hurricane Sandy broke records and may well have contributed to a shift in opinion on climate change and possibly helped to swing the election in America. Then Christmas 2012 in the UK was filled with reports of severe flooding, travel delays and damage to property, coming at the end of a year that is the second wettest on record. News stories tend to focus on personal stories, injuries, economic costs and daily inconveniences, but rarely touch upon the impact of these events more broadly on urban systems, and the wider actions that governments need to take to mediate risk and manage impacts on vulnerable populations. In cities in developed countries like the UK, there are contingency plans and reasonable infrastructure for extreme events, but this isn’t the case for all cities. Beyond thinking about discrete climate events, in the developing world, the sheer rate of urbanisation means that poor neighbourhoods in many cities have sprawled onto floodplains and unstable hillsides, which is combined with insufficient infrastructure and services to support health and wellbeing. In many cases, rapid urbanisation has also been both bad for the environment, and for people. Inequality is exacerbated by the unmet demand for housing, services, transport and work. Cities themselves can contribute to ill health and obesity through poor urban planning, inadequate transport provision, pollution and unsafe roads. A lack of or poor regeneration and planning often results in damage to our mental and physical health. The concept of interlinkages between cities, health and climate change has only fairly recently started to come to the fore. When the 2008 UCL/Lancet Commission on the effects of climate change on health was first published, attention was focused on the big uncertainties and risks to health: changing patterns of infectious disease, and indirect impacts of famine, political instability and migration. Although excess deaths due to heatwaves were identified, there was little discussion of the particular vulnerabilities of people in informal settlements. Since then, droughts, storms and floods have also shown the potential for climate change to take us by surprise, and that greater effort and funding for mitigation and adaptation are needed now. Megacities at risk There is increasing urgency to focus our attentions on cities, and it is predicted that the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people living in cities will be affected by climate change over the next 5-10 years. The humanitarian imperative isn’t the only one: we must also remember that the most vulnerable have in general contributed least to atmospheric greenhouse gases. According to a UNFPA report, half of Africa’s 37 ‘million cities’ are at risk from sea-level rise and storm surges. Many Asian cities are in the floodplains of major rivers such as the Ganges, Mekong and the Yangtze. Climate change will have complex impacts on cities, and is exposing vulnerabilities in the social, economic and political fabric of our communities. The longer we wait, the more it will cost – not just in GDP as outlined by the Stern Review but in health, and in lives. We can’t just go on with business as usual. It’s not all bad news – urban environments can also allow new forms of social organisation to lead the way and offer new solutions. Cities can offer a possibility for decoupling high standards of living from high carbon footprints, and a small effort may lead to big change because of their centralised nature – for example in improving roads for pedestrians and cyclists to use. There is a range of ways to change policy and in turn change physical realities. Karachi’s Urban Resource Centre – an organisation founded by teachers, professionals, students, activists and community groups from low-income settlements – has successfully challenged government plans, showing that community action can make a difference to those living closest to the edge. For the first time in history, half the world now lives in cities, and this number is set to continue growing. We need a concerted effort to improve our global cities by putting systems in place to facilitate environmentally sustainable and healthy lives and ensuring that they are adapted to climate risk and able to protect the most vulnerable.  Land degradation (source: UN/John Isaac) Land degradation (source: UN/John Isaac) Dalvir Kular With conservative estimates forecasting a population of around 9 billion people by 2050, the question of whether the world food system’s production capacity can keep up with increasing demand is a very important one. How it can do so in a world increasingly influenced by climate change is an even tougher question. Imagine if 2013 were the year where we started to take real action on climate change. The year where we changed our course to end malnutrition, for good. I choose to be optimistic. In the global north we have warped our basic need for food into a multi-billion pound industry in which it’s not so much about nutrition but luxury…at least as long as you have the money. In the global south, the losers of our success are driven further into poverty, due to injustices in the political decisions of the global north. The lack of regulation, commodity speculation, inequitable trade policies and climate change combined are helping to send food prices through the roof for the poor. The recent launch of the ‘Enough Food For Everyone IF‘ campaign hammered home the truth that for now, there is enough food available to feed everyone on Earth, but the real problem is how to ensure that people have sufficient access to ensure their food security. Unsustainable energy use and agriculture are fueling a warmer climate, which is resulting in unpredictable and increasingly frequent natural disasters such as floods and droughts. The problems described above – and the increasing shadow of climate change – are directly and indirectly impacting on access to food for the world’s poor; and climate science tells us there’s more to come. Safety nets and speculation According to the United Nations global food reserves are at their lowest levels in nearly 40 years, meaning that there’s a much smaller margin for those already food insecure. If the cost of staples goes up 170%, people either increase their expenditure for the same amount of food, you change your diet to a cheaper and often less nutritious one or you eat less. If you’re poor, ie. when the food required to be secure represents a reasonable proportion of your income, the first option may not be open to you, and there is much less scope to adapt. Rapid urbanisation in the developing world creates the opportunity of greater inequality of livelihoods and income in a higher population density. This give rise to possible future food security issues and a need for safety nets to help city dwellers cope when food prices may be volatile in the future. Helping farmers to adapt to the impacts of climate change can defend food supplies. Laws to prevent speculation have been largely opposed by the big players. Barclays is the biggest UK operator in food commodity markets, making up to an estimated £500m from speculating on food prices in 2010 and 2011. Legislation to limit commodity speculation was backed by the EU in early 2013. Germany’s fourth largest bank, DZ Bank, has announced it would no longer speculate on food prices. Agriculture – especially large-scale, intensive farming of livestock – contributes heavily to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which in turn are a big part of the reason why we’ve been seeing crop failures all around the world, from Africa to the USA to Russia. Agriculture needs to be part of the solution – and with an increase in investment and better policies, sustainable agriculture technologies and practices may be adopted to improve food security and sovereignty for farmers and consumers in the global South, and to reduce emissions and preserve biodiversity. The recent extremely successful UK-based Fish Fight campaign, spearheaded by the food writer Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, is proof that people power – assisted by the internet and social media – can bring real change. It coordinated its supporters to send emails to MEPs in all the official languages of the EU, with more than 120,000 sent within 24 hours in a, successful, effort to ban fish discards. We need similar political momentum to set a more ambitious 40% emissions reduction target for Europe. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which receives nearly 40% of the EU budget must be reformed along the lines advocated by the ‘Enough food for everyone IF’ campaign. It suggests stopping food from becoming fuel for cars, a false economy when it comes to tackling climate change. Certainly we in Europe should pressure our MEPs to lobby for sustainable agriculture in the context of the CAP reform being carried out this year. The idea of a low GHG diet – more domestic, home grown foods, seasonal, local, and including less red meat and dairy – is far from new, but it’s one of the ways that people can make the biggest difference to their carbon footprint. The really good news is that it isn’t only more sustainable, but also often healthier too.  (Source: Flickr/USAID Kenya) (Source: Flickr/USAID Kenya) Laura Pearson The evidence for climate change is compelling: during the last decade we have experienced eight of the warmest years on record. Global surface temperatures are predicted to rise above the 2⁰C threshold – and possibly dramatically so – within less than a century. But what does that mean for health? I recently attended a discussion by speakers Hugh Montgomery, Ian Roberts, Anthony Costello and David Satterthwaite, experts on different aspects of health in a warming world. They discussed current climate science, current and projected impacts on health – through extreme events and threats to shelter, food and water security, ecosystem and economic stability – and health co-benefits. Vector-borne diseases, which are transmitted by insects and mites or ticks, including serious diseases like malaria and tick-borne encephalitis, were not discussed much, but they have strong associations with the climate and are clearly an important influence upon global health. They account for 16% of the estimated total global disease burden for all communicable diseases and the majority of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) – diseases that affect a billion people, yet receive comparatively little attention or funding. Also of importance is how climate change can impact directly upon these diseases, because of their strong associations with poverty and the effects climate change has upon economic stability. Climate also impacts upon food and income generated by livestock, via diseases such as African Horse Sickness and Bluetongue, therefore further affecting economic stability. The predicted escalations in temperatures, precipitation and humidity will influence both intermediate host and vector ecology and biology, and also interact with other factors like urbanisation and increasing volumes of global trade, making the influences on transmission dynamics very difficult to predict. What is clear is that they are potentially very large, making a strong case for a precautionary approach. In a warming climate, a number of mosquito species can develop and reproduce faster, which can increase population growth and biting rates, and therefore the transmission of diseases they carry, such as malaria, dengue and yellow fever. Rainfall is also important. During the 1997-1998 El Niño, precipitation shifts led to explosions in mosquito populations, evoking epidemics of the most dangerous species of malaria. Areas that receive less rain could also have negative impacts on vectors: Anopheles funestus mosquitoes for example virtually vanished from Senegal due to reduced precipitation rainfall, resulting in a 60% reduction in malaria prevalence during 1970-2000 in Senegal. However, changes in ecosystems which negatively impact one vector species can benefit others. In a dryer, warmer environment, a species of Tsetse fly which thrives in dry savannah regions and is responsible for spreading a particularly virulent strain of sleeping sickness, is predicted to increase. Indirect environmental factors Changing ecological factors, including but not limited to climate, can create new selective pressures on vectors: for example, deforestation and increasing urban sprawl have most likely contributed to the vector for Chagas disease, becoming adapted to feed on the blood of encroaching human populations. It has shifted from a diet primarily involving wild animals to one where it feeds primarily upon people in their own homes, and so increasing disease prevalence. And the problem is not confined to developing countries: warmer winters have enabled the Asian tiger mosquito to establish itself in Italy, presenting serious potential risks of dengue. Tick-borne encephalitis and Lyme disease could also be supported throughout Europe by thriving tick populations. In addition, globalisation and increasing rates of air travel put us all at risk of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases even if they first manifest themselves in populations on the other side of the world. The short- and long-term consequences of climate change will ultimately influence the ecology, transmission, dispersal and evolution of a range of vector-borne diseases across the globe in important ways. These will interact with many other impacts, such as economic effects and population displacement to result in direct and indirect health impacts. The most obvious corollary of this story is the need for rapid and urgent action to mitigate climate change. Nevertheless, we also urgently need to prepare more effectively for unavoidable infectious disease risks associated with climate change: modelling to predict potential threats, vigilant surveillance and epidemiology, and adequate, well-targeted funding will all be essential for effective and efficient disease prevention and control strategies. Originally published at http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/31/time-to-protect-against-climate-aided-spread-of-disease/ Isobel Braithwaite

The direct impacts of natural – and, in a warming world, (un)natural – disasters are relatively straightforward to quantify. They are also probably some of the easiest health impacts of climate change to evaluate (albeit with the caveat that we can only attribute trends to climate change, not single extreme weather events). The deaths and injuries, and the epidemics that can happen in the wake of a flood or hurricane are in some ways more easily attributable than the impacts of extreme heat, or those of air pollution exacerbated by a heatwave. Even so, the effects of extreme weather events on health, especially the longer-term impacts, can be difficult to evaluate fully. Often they’re not the things we think of straight away: carbon monoxide poisoning or exposure to cold and mould for example, leptospirosis (an infection spread by rats) or even allergic reactions to bee and wasp stings, which have been shown to increase after hurricanes and flooding. Then there’s what happens when the medical services are overwhelmed or a power outage makes storing drugs difficult. Pre-existing conditions often aren’t properly managed and deteriorate at that point, putting peoples’ health in danger further. In addition to deaths from drowning and the physical health impacts of injuries, hypothermia, water-borne diseases etc, extreme events can also have severe and long-lasting effects on psychological wellbeing. A month after Hurricane Katrina, 17% of residents reported signs of serious mental illness – compared to a general population average between 1 and 3%. Inequalities Equally important to bear in mind is the importance of inequality, which is a recurrent theme in practically all research and literature on climate change and health. In the parts of the world where the biggest impacts from extreme weather events occur, generally those least responsible for causing climate change, there is often far less surveillance or data collection capacity and infrastructure to be able to assess the extent of impacts accurately than where we have more adaptive capacity and are better prepared. In turn, this means we may well be underestimating the true, global extent of the health effects of such events. To take a recent illustration of these themes, Hurricane Sandy caused at least 71 deaths in the Caribbean and approximately 100 in New York, and had immense and devastating impacts on the economy and on peoples’ lives, which are still continuing for too many people. Had it made landfall somewhere poorer such as a Central American country, the death toll could have been significantly higher. Most likely it would also have received less coverage had it hit a poor country. The side of Sandy that we heard much less of in the international media was the fact that it left 21,000 Haitians homeless and 1.5 million in a situation of severe food insecurity. Many of these were already in an extremely vulnerable situation after the 2010 earthquake and tropical storm Isaac two months prior to Sandy. After Sandy, Congress approved a $9.7bn aid package, and has more recently approved $50 billion. On top of that, $854m was pledged by the international community. Compare that to 1998’s Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua, where around 3800 people died (of 11000 total across Latin America) and more than a million were left homeless. In total, the aid received was just over $118.5m, based on the sum of the Secretariat of External Cooperation and the Red Cross Federation’s total figures. Although the scale of need was arguably much greater, total funds were around 100 times lower than even the early US aid package for Sandy and nine times less than the international pledges made, including by countries as poor as Afghanistan and Uganda. A recent report found that the total impacts of climate change on the global economy are of the order of $1.2 trillion, as well as contributing to 400,000 deaths. But determining and predicting the role of climate change in the spread and emergence of new or re-emerging infectious diseases is significantly more complex, especially when we try to integrate the effects that extreme events can have on infectious disease patterns, often in unpredictable ways. In turn, investigation of how extreme events affect food and water security or – even less directly, economic stability or conflict – is even more complex. I find it helpful to think of climate change as a threat multiplier rather than a causal factor, but it is the extremes where the real health risk, and the real unpredictability, lies. The causal chain is so much more complex, and the effects less easily demonstrable, yet these could potentially have much bigger effects on health, than the more direct impacts. Threat multiplier Although hurricanes aren’t caused by climate change as such (see the IPCC’s report on extreme weather) there is good evidence that when they do occur such storms are made stronger by its other effects. Rising temperatures mean more moisture in the atmosphere – for every 1°C rise, air can hold 7% more moisture – resulting in much heavier rain. Climate change also drives rising sea levels and so an increased risk of storm surges. The global sea level has risen approximately an inch in the last decade alone, which further increases the threat when landfall coincides with an extra-high tide, as in the case of Sandy, and flooding can start even before landfall. The Weather Channel’s senior meteorologist Stu Ostro said Sandy represented “a meteorologically mind-boggling combination of ingredients coming together…an extraordinary situation.” The odds are that it has made ones like Katrina and Sandy more severe than they would have been without it – yet in the sort of irony you really couldn’t make up, $400m of the international pledges made, were offered in oil. Events like these are also part of an ongoing trend of more frequent and more extreme events in recent decades: this series around the globe last year, taken together, are unprecedented in their size and frequency. The health effects of extreme weather can be severe, even in rich countries, and much worse in poor ones: we can’t afford to hope they’re all just coincidences, and we can’t afford to wait.  The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) The military supply water in Dhaka (Source: UN/Kibae Park) Izzy Braithwaite Originally published at: http://www.rtcc.org/2013/05/27/comment-health-overlooked-in-our-response-to-climate-change/ The protection of human health and wellbeing is a central rationale for the emissions reductions called for in the very first article of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Yet, somehow, the issue is missing from many parts of the UN talks. The growing body of research and evidence in the area over the past couple of decades hasn’t really translated into a broader understanding of how climate change and health are related, beyond a relatively small community of academics and health professionals. Knowledge about the links between climate and health among the public, climate negotiators and environmentalists is often limited and quite superficial. It typically doesn’t stretch far beyond the more direct impacts, such as heatwaves, vector-borne diseases or extreme weather events such as flooding. Indirect effects on health are rarely considered, and both the media and the public tend to frame the impacts of climate change in terms of the risks to ecosystems and species or economic losses; very rarely in terms of its other impacts on people and their health. Perhaps this is part of why climate mitigation and adaptation measures fail to get the levels of both political and financial support they need to tackle climate change and to protect and promote health in the face of it: current levels of adaptation finance, much like current emissions reductions pledges, are grossly inadequate. As a glance at any newspaper or polls about the relative political importance of different topics make clear – most of us are concerned about our own health and the health of those we care about, including that of our children and grandchildren and less visible problems like climate change, which are also delayed in time, often feature far below this on the agenda. Climate change will dramatically affect the health of today’s children and young people, and more than that, policies to promote the health ‘co-benefits’ of sustainability and climate action could greatly improve health. Surely those messages, if communicated more effectively, could be a strong driver to help us achieve the sort of rapid, meaningful changes we need in order to avoid catastrophic climate change - couldn’t they? In the UK, several thousand health professionals have joined the Climate and Health Council to add their voice to a global climate and health movement which already has strong voices in Australia, Europe and the US, along with several other regions, and they are starting to connect up, for example with the Doha Declaration. Doubt is their product... At the same time, communication with negotiators, the mainstream media and the wider public around what’s known about climate and health clearly hasn’t yet been very effective, and has been compounded by the confusion that biased and inaccurate media such as Fox News and the Murdoch empire seek to create. This is very much like the 'merchants of doubt' phenomenon that emerged among tobacco companies as the evidence of tobacco's health risks came to light. One of my friends recently asked me when he saw this video, “if climate change is really such a big health threat, then why don’t most people know that, and why isn’t it mentioned more in the news?” I’m convinced by the evidence that it is – some of it is collected in our resources section– but I found it hard to answer his question. Have we all, consciously or subconsciously, decided that it’s too depressing so we don’t want to know, do the media decide it’s not worth broadcasting, is it related to the success of fossil fuel companies and their PR and lobbying teams, or is it something else? I don’t have the answers, but I think there are many reasons: for one, picking out long-term trends to ascertain what health impacts are attributable to climate change is no easy task, and – especially when it comes to modelling future health impacts which are often highly dependent on socioeconomic factors too – the science is far from simple. Predictions, of necessity, depend on various assumptions and on multiple interacting factors. As with climate change in general, the real-world effects are highly uncertain: not because scientists think health might be fine in a world four or six degrees hotter, but because it’s very hard to work out exactly how bad the impacts may be. Even the World Bank now explicitly recognises that this is what we’re currently on course towards, that it’ll be far from easy to adapt to, and that such a temperature rise would conflict greatly with its mission to alleviate poverty. The dangers of ignoring Black Swans As George Monbiot pointed out in characteristically optimistic style last year, mainstream global predictions for future food availability in the face of climate change may be wildly off – because they’re based only on average temperatures rather than the extremes. A fatal error if this is true that the extremes – droughts, wildfires and so on – could become the main determinant of global food production, interacting with other changes to affect in ways that, like Taleb's 'Black Swan' events, are almost impossible to predict. If this does turn out to be the case, it’s likely that by far the biggest health impact of climate change will be malnutrition, as argued by Kris Ebi, lead author of the human health section of the last IPCC report. Inadequate food intake not only increases vulnerability to infectious diseases such as malaria, TB, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease, but also kills directly through starvation. Food insecurity, in turn, can force people to migrate just as something more obvious like sea-level rise can, and this can be a driver of civil conflict. Both migration and conflict of course have major physical and health impacts, but their extent and distribution depend on numerous other things; climate is one driver among many. Like any give extreme weather event, it’s hard to attribute indirect effects of climate change such as these to climate change, given how strongly it interacts with other contextual factors. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a causal relationship. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment showed in 2005, our health and wellbeing ultimately depends on ecosystem functioning and stability, at levels from local to global. How ecosystems and in turn health are being – and will be – affected by climate change is unavoidably complex. That makes it hard to communicate and hard to use to change policy, but we cannot allow this to stop effective advocacy and action. The fossil fuel industries and the many dubious institutions and individuals they fund will not wait: with billions made from the sale of coal, oil and gas, they are much better organised and resourced than us at present, and they will use every opportunity to maintain doubt, prolong inaction and ensure that our future isn’t allowed to compromise their sales. In order to extend a sense of the importance of climate action beyond the environmental community and to secure broad and deep consensus on the need for concerted action, health must play a much bigger role in decision-making at all levels. Both impacts and health co-benefits need to feature more centrally in national mitigation and adaptation plans, and in our discussions around climate change more generally. That shift won’t happen on its’ own, and with the Bonn UNFCCC intersessionals coming up in June, it strike me that health should be a priority. Better resourcing and a comprehensive work programme including capacity-building, education and raising public awareness on subjects specific to climate and health would be a tangible and positive way to protect and promote health and to reduce the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable.  Izzy Braithwaite A few weeks ago, I went to an Enough Food IF training day, organised by a number of the big organisations behind the campaign. It aimed to give us the background needed to visit our MPs to talk about two of the main asks – aid and tax – in advance of the Budget and the Finance Bill. The question the IF campaign asks is ‘IF we produce enough food to feed everyone, why do one in 8 people go hungry?’ The crux of the argument is that IF we can change a number of key things about our current system, we can make sure everyone gets enough to eat. I couldn't really argue with that, and I decided I wanted to meet my MP about it - which I did as part of a group on Friday afternoon, and really enjoyed. How is the campaign linked to climate and health? I’ve been interested in global health for several years, focusing more recently on how climate change affects, and will affect, global health, which is how I got involved in Healthy Planet. It seems to me that one of the big impacts climate change is having on people in the poorest countries – and one of the biggest effects it’s likely to have on health in the future - is through food. It makes a lot of sense to me that IF we can build a fairer food system, including through changes in the way tax works for developing countries, that will help reduce the impact of climate-induced crop losses on the health of the poorest. Although the Enough Food IF campaign doesn’t focus explicitly on climate change, there’s a fair amount of evidence that land grabs, food price speculation and short-sighted biofuels policies – all of which the campaign aims to highlight and tackle – act alongside more unstable weather and inadequate social security to push more people into food insecurity. But even if it weren’t for climate change, we have massive injustices around food and access to it; climate change just exacerbates them. You can't really disagree that a world in which almost a billion who don’t have enough to eat while so many others throw away as much as they do, and while so many people are suffering the health effects of obesity, is kind of crazy. Tax and development I didn’t know a lot about the ins and outs of tax policy and how it related to international development before getting involved in the IF campaign, but came away from the training day and my reading online afterwards with a better understanding. I learnt how crucial tax revenue is in enabling developing countries to finance public services, and had no idea that tax avoidance currently costs them to the tune of 3 times as much revenue as they receive in aid each year. I was shocked to learn how Associated British Foods, which produces vast quantities of sugar in Zambia – a country where many people struggle to afford enough to eat – has managed to ensure that it pays less tax in Zambia than the woman in this ActionAid video, a shopkeeper who sells their sugar. Then there was the story about the Rwandan revenue authority, set up with a grant of £24 million from DfID, which now generates that much in tax every 3 weeks. Talk about value for money. That revenue stability enables the Rwandan government to finance essential public services like schools and healthcare, and helps it to ensure that it’s people have enough to eat. If we want aid to be effective and countries to be able to finance aspirations like Universal Health Coverage, tax should be a global health priority, and it was great to have some real examples to illustrate that at the meeting.  The meeting Alison Marshall, who works at Unicef UK and had signed up as a coordinator for my borough on the online lobbying forum, managed to set up a meeting with my MP Jeremy Corbyn for yesterday afternoon, and put everyone who’d expressed an interest in touch with the other interested people in Islington North. About half of those on the email list were able to make it, with quite a range of ages, jobs and backgrounds. Most of us had never met one another before the meeting, so we divided up tasks and subjects in advance and turned up for a chat half an hour before. Unforeseen circumstances meant the office was unavailable that day so we had to relocate, but fortunately an incredible woman called Theresa had offered up the nearby Finsbury Park Community Centre for the meeting. She filled us in on what things are like in the ward, which is one of the most deprived in England, and it was sobering to hear some of the statistics and stories. I'd read a bit about Mr Corbyn’s voting record and past involvement in international development-related work, so I had thought he would probably be happy to support the 0.7% aid goal, but I hadn’t known how he’d respond to the ask on tax transparency, which is a relatively technical one and took more explaining. It relates to the upcoming Finance Bill, and specifically asks that it extends DOTAS (disclosure of tax avoidance schemes) rules to any which impact on developing countries, in order to help them tackle tax avoidance by multinational corporations operating in their countries. The DOTAS regulations help tackle corporate tax avoidance in the UK, and it essentially requires companies to disclose any schemes they use to get out of paying tax. The IF ask (briefing here) is to introduce a similar requirement for UK companies and wealthy individuals to report their use of tax schemes with an impact on developing countries. It also asks that the bill require that when such schemes are identified the UK will use its existing powers under bilateral and multilateral treaties to notify developing countries’ tax authorities, and to assist in the recovery of that tax. Of course, transparency doesn’t in itself prevent tax avoidance, but it does make it much easier to hold companies accountable, and helps to enable developing countries to enforce and improve their laws. And of course UK action is not the whole of the answer – that will include international cooperation, which hopefully the G8 will make progress on, and country-by country reporting amongst other things. But it would be a good step on the road towards a fairer and more effective tax system, and could potentially set a useful precedent for other countries, and the EU, to follow. I quite like a challenge, so I’d kind of hoped we’d have to argue our case a bit more, but in fact he was very much in agreement with both of our asks, and agreed to write to the Chancellor and to lobby other Labour MPs and to raise it after the Budget and the Finance Bill. I suppose I can hardly complain that I have an MP who cares about international development and takes an interest in the details of how we should contribute to it even though most of his time is spent dealing with much more local issues. He told us about some of the problems he'd been trying to fix recently, such as the story of a guy who’d been sleeping on a bus for months who he’d just spent the afternoon trying to get re-housed. I hadn’t really thought there would be many parallels between politics and medicine before the meeting - not least because doctors tend to be trusted by the public whereas many politicians aren’t - but if I'd had to guess his job without knowing, I could easily have guessed a doctor or an overworked social worker. Both are both more of a lifestyle choice than a nine-to-five job, and both doctors and politicians have the opportunity to change peoples’ lives for the better.  Now is when the real test for the campaign begins - making sure there's enough pressure, and enough other MPs on board - to push through specific reforms. Which is where you come in... How can you get involved?

Jonny Elliott The issue of climate-forced migration, and its impacts on human health, is a discourse that is often underplayed when it comes to discussions about climate impacts and adaptation. The ramifications of ignoring it, and consequently failing to put in place appropriate policy frameworks to cope with increased levels of migrants at an international level, will be huge. The health problems associated with climate-related migration also pose a major challenge for existing healthcare systems and the international humanitarian response.

According to International Organisation for Migration and United Nations figures, between 200 million and 1 billion people could be forced to leave their homes between 2010 and 2050 as the effects of climate change worsen, potentially inundating current response strategies. Climate change migration is already happening across the world - right now. Some are migrating because of the direct impacts of natural disasters like floods, droughts and acute water shortages. Whilst indirect impacts such as conflict and increases in food prices can also contribute to people being forced to leave their homes. There is no doubt that forced migration due to climate change will increase the pressure on existing infrastructure and urban services, especially in sanitation, education and social sectors and also consequently increase the risk of conflict over access to scare resources, even amongst migrants. A study released on 28 November, entitled ‘where the rain falls: climate change, food and livelihood security, and migration’ reveals a much more nuanced relationship between projected climate variability and migration, which could provide key insights into likely drivers of migration the coming years. The study, carried out by CARE International and UN University, in 8 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, revealed that in nearly all instances in which rains have become too scarce for farming, people have migrated, but mostly within national borders. At a side event at COP18 on this issue last week, one of the authors, Dr Koko Warner, remarked that "those resilient households use migration to reduce their exposure to climatic variability… In those households, migrants are in their mid-20s, single, move temporarily and send remittances back home. Those resilient households use migration to invest in even more livelihood diversification, education, health and other activities that put them on a positive path to human development." However, there are also much starker consequences for more vulnerable households: 1. Households may migrate in an attempt to manage risk but suffer worse outcomes. They are found in countries with less food security and fewer options to diversify their incomes. They move within their countries seasonally to find work, often as agricultural labourers. 2. The study also described how migration could be an ‘erosive coping strategy’; as a matter of human security, when few other options exist. These households are found in areas where food is even scarcer. They often move during the unpredictable dry season to other rural areas in their regions in search of food or work. 3. Lastly, the study found "households that are trapped and cannot move, and are really at the very margins of existence," according to Warner. These households do not have the capacity to migrate. Health policy making in the context of migration can either been seen as a human rights issue, putting the needs of the individual first, or as a security issue, in terms of its threats to public health (eg. communicable disease control) and social stability. The latter approach relies principally on monitoring, surveillance and screening, and could be argues to be the modern-day cousin of centuries-old quarantine measures, without an individual-focused perspective. The human-rights based approach takes into account nuances and special needs of individuals, as well as the social determinants which may have affected individuals’ health along the migratory pathway. With respect to the UNFCCC process, the response to environmental migration is an area that is particularly underdeveloped. The negotiating text elaborated at Tianjin in 2010 invited Parties to enhance adaptation action under the Adaptation Framework through: [‘m]easures to enhance understanding, coordination and cooperation related to national, regional and international climate change induced displacement, migration and planned relocation, where appropriate’. The Cancun agreement in 2010 took some strides forward and laid out a roadmap for progress with reference to migration, but as yet it hasn’t been implemented, and highlights the need for better and more equitable policy at a global level. As Jane McAdam observes: “Finally—and perhaps most significantly—there seems to be little political appetite for a new international agreement on protection. As one official in Bangladesh pessimistically observed, ‘this is a globe for a rich man’. In “Migration and Climate Change,” a recent publication by UNESCO, Stephen Castles, Associate Director of the International Migration Institute at the University of Oxford suggests that we may need to re-think our strategy. “The doomsday prophesies of environmentalists may have done more to stigmatize refugees and migrants and to support repressive state measures against them, than to raise environmental awareness.” We should be doing more, much more, to raise awareness of this issue, and we must start preparing to cope effectively with the health issues associated with it. |

Details

Archives

February 2019

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed